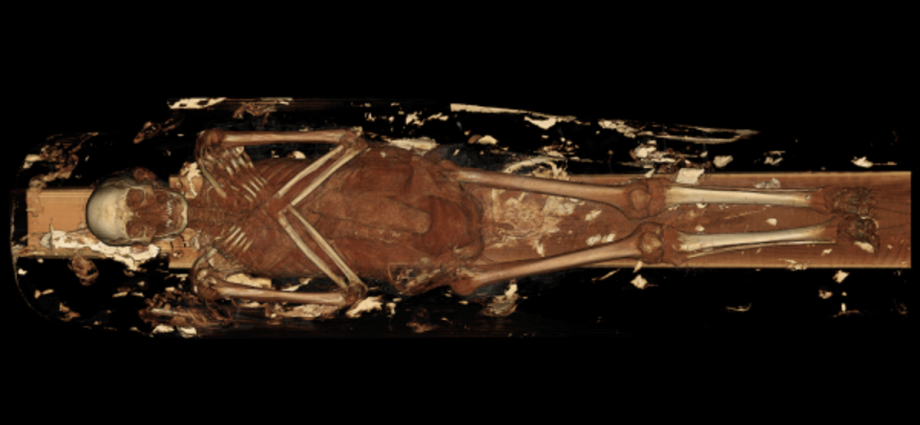

X-ray scans conducted on a 2,000-year-old mummy have revealed that the ancient Egyptian lived with an aching lower back, not unlike many modern humans.

Radiologists subjected two mummies dated to 330BC and 190BC to computed tomography (CT) X-ray scans, offering a view into the lives of ancient Egyptians over 2,000 years ago.

The analysis revealed their facial features, including shapes of their eyelids and lower lips, as well as clues about their health, life experiences and lifespans, which may resonate with people today, scientists say.

Researchers from the Keck Medicine team of the University of Southern California (USC) scanned the inside of the bottom half of the mummies’ sarcophagus, each weighing about 90kg (200 lbs).

Researchers found that the elder of the two mummies suffered from an aching lower back. The ancient Egyptian was buried with several artefacts, representing several scarab beetles and a fish. Scans revealed his spine had a collapsed lumbar or lower back vertebrae, likely due to natural aging and wear and tear. The other individual appeared to have had dental issues and a severely deteriorated hip, and that he was older at the time of death.

These linen-wrapped mummies, along with 3D digital models and insights from their scans, will be presented at an upcoming exhibit at the California Science Center from 7 February.

“Seeing beneath the surface to reveal the specific lived experience of individuals is incredibly exciting,” said anthropologist Diane Perlov, senior vice president for special projects at the California Science Center.

“This modern scientific technology offers us a powerful window into the world of ancient people and past civilisations that might otherwise be lost,” Dr Perlov said.

CT scans create hundreds of detailed 3D cross-sectional images, or “slices”, which then experts can digitally “stack” to form digital models.

Used widely in surgery, they now offer means to conduct non-destructive analysis of ancient specimen like mummies.

“Through 3D visualisation, modelling and printing, clinicians like surgeons can accurately measure hard-to-detect tumors, examine the intricate structure of a patient’s heart or liver or determine how best to repair a shoulder or hip,” said Summer Decker, who leads 3D imaging for Keck Medicine.

“These mummies were scanned previously, but due to advancements in scanning technology, the results are much more detailed and extensive than ever before,” said Dr Decker, adding that the new high-resolution images reveal “things that were previously unknown and helped create a picture of what their lives were like”.