Archaeologists have uncovered what could be the largest cluster of houses ever discovered in the entirety of prehistoric Britain and Ireland.

Until now, the largest cluster of ancient settlements known in Ireland was Mullaghfarna, an archaeological site in County Sligo.

The mound is thought to have contained over 150 houses during the middle Stone Age period of 3300–2900 BC, and also in the later Bronze Age period between 1200–900 BC.

Now, researchers have found evidence of an even larger settlement containing over 600 houses existing in prehistoric Ireland during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age periods between 3700-800 BC.

The prehistoric house remains were unearthed in County Wicklow, Ireland.

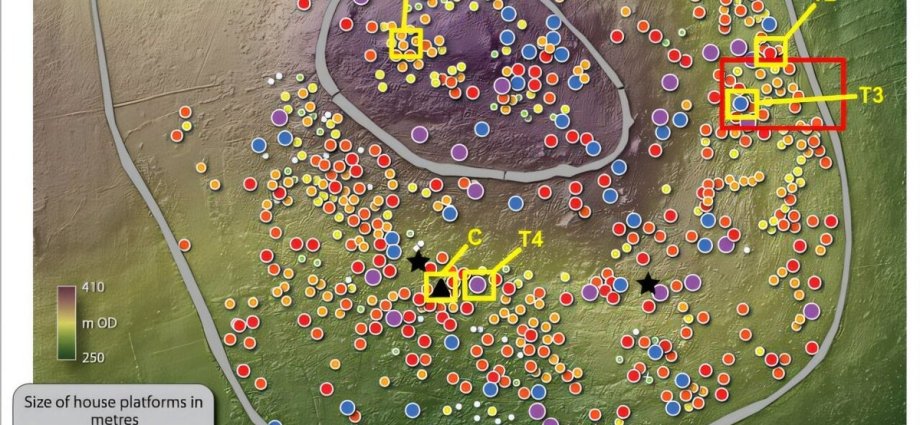

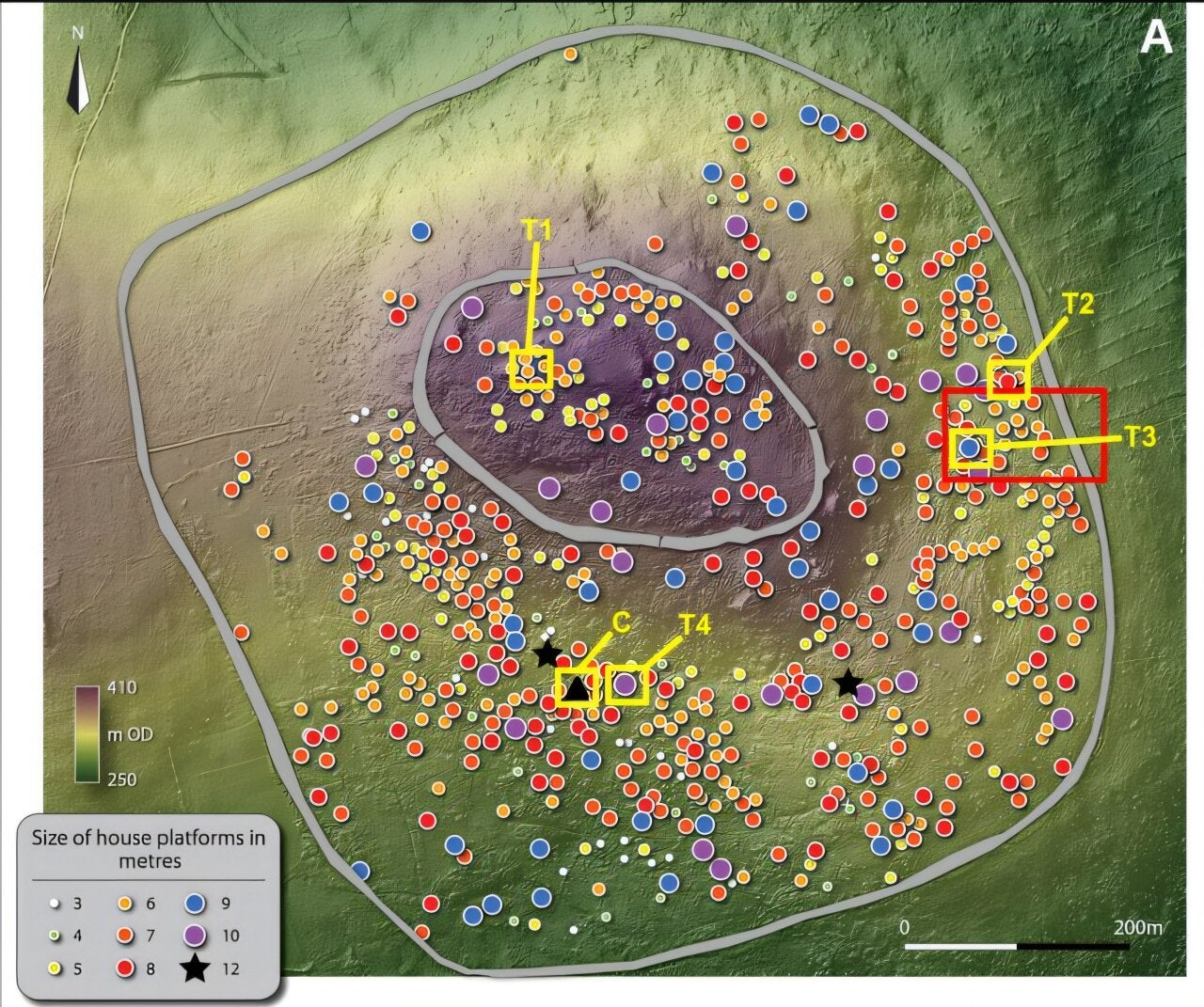

This region, called the Baltinglass hillfort cluster, has up to 13 large hilltop enclosures spread across a “necklace” of hills at the south-western edge of the Wicklow Mountains, with at least seven major hillforts and several additional enclosures.

It shows signs of continuous use and monumental construction from the Early Neolithic through to the Bronze Age between 3700 to 800 BC, say researchers from Cambridge University.

Within this cluster, there is a unique structure called the Brusselstown Ring with two widely spaced ramparts encompassing the enclosure.

Air borne surveys of the Brusselstown Ring have suggested that it could have had over 600 suspected house platforms, of which 98 were within the inner enclosure and the remaining 509 between the inner and outer enclosing elements, making it the largest clustered hillfort settlement in prehistoric Ireland and Britain to date.

“This site – along with a small number of other nucleated settlements situated on hilltops – appears to have emerged around 1200 BC,” said Cherie Edwards, an author of the study published in the journal Antiquity.

The findings, according to researchers, suggest early city development in Northern Europe likely occurred nearly 500 years earlier than previously thought.

“Excavation trenches were deliberately positioned over house platforms of varying diameters (6m, 7m, 8m, and 12m) to assess potential correlations between house size and indicators of social differentiation,” Dr Edwards said.

“The settlement clearly dates to the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (1193–410 BC) and represents a nucleated or agglomerated site characterised by a high density of dwellings,” he said.

Archaeologists also unearthed a unique structure near one of the trenches with a flat interior outlined by large stones.

With previous surveys suggesting that a stream once flowed into the structure from uphill, scientists suspect this might be a Bronze and Iron Age water cistern – that could represent the first of its kind in an Irish hillfort.

However, researchers call for more research to better understand the extent and nature of Brusselstown Hill’s potential water cistern.

“The site’s chronological trajectory aligns closely with that of other, albeit smaller, hilltop nucleated sites in Ireland, implying that its abandonment followed a broader regional pattern of gradual decline during the Iron Age, around the third century BC,” Dr Edwards said.

“This decline also appears unrelated to the climatic shift toward cooler and wetter conditions that began during the Bronze Age–Iron Age transition, 750 BC,” he added.