Teachers could follow resident doctors and strike next year unless Labour hikes pay and plugs school funding gaps, the bosses of two major teaching unions have warned.

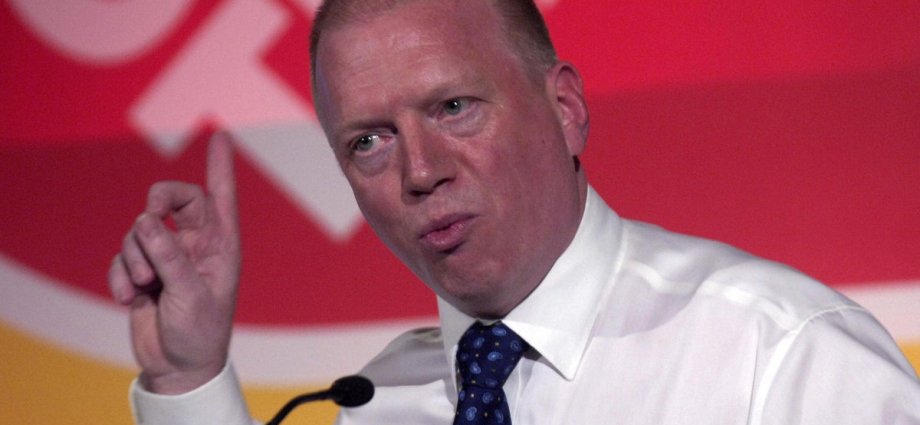

Matt Wrack, general secretary of the National Association of Schoolmasters and Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT), told The Independent that talks of strikes were “inevitable” at the union’s conference next April unless there were improvements in pay and conditions. He argued cash-strapped schools were caught in a “vicious cycle” because teacher pay rises had to come out of existing school budgets, which were already stretched.

Mr Wrack warned members “expected change” after Labour won the general election, but they are “not convinced that change is being delivered, either adequately enough or quickly enough”.

Meanwhile, Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT), warned there is a “real possibility of industrial difficulties” next year, arguing that teachers may no longer tolerate the “burden of pressure” being placed on them.

The latest School Workforce Census revealed that there were almost 3,000 fewer state primary and nursery school teachers in England in 2024, with one in five (19.4 per cent) teachers in primary and secondary schools leaving the profession within two years of qualifying. That figure rises to more than one in four (26.7 per cent) after three years.

In May, the government accepted the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) recommendation of a 4 per cent pay rise for the 2025-26 academic year – a recommendation Mr Wrack described as being “unhelpful” when teachers’ real earnings “have fallen over the past 15 years”.

“There’s been changes to pensions which have worsened pensions. So the package that teachers get is not what it was 15 years ago.

“It [the STRB] seems to us to suggest that we might have two or possibly three years of low pay rises, which may be below even the government’s measure of inflation, but certainly below how we assess inflation using RPI, and that additionally, those pay rises are not going to be adequately funded”, he said.

Dubbing this a “vicious cycle”, he explained: “So we get a low pay rise, but if we get a slightly higher pay rise, that just exacerbates the crisis in the schools.”

Asked whether England will see teacher walkouts next year, the union boss said: “I think that teachers at our union, undoubtedly, by our conference next April, it’s inevitable there will be a discussion about industrial action. I think at least it will come up as an option for people to consider.”

The warning comes after resident doctors launched five days of strike action, between 17-22 December, as they continued their fight with the government over training and pay.

While Mr Wrack, a former TUC president and Fire Brigades Union chief, acknowledged there has been “some easing up on pay”, he said the government has failed to resolve “the pressures” on teachers, such as excessive workloads and a recruitment and retention crisis, which he said had been caused by long-term underinvestment.

Mr Whiteman agreed there was a “real possibility” of industrial difficulties next year.

He said: “Whether that’s a walkout or other industrial action, I don’t know, but I think what will come to a head is the whole package of difficulties.

“I don’t think it will be just pay, I think it will be about workload and working hours and just the intensity and the danger of work.”

While he argued the government has a “huge ambition for education”, he does not believe that ambition has yet been backed up with “the right resources”.

Mr Whiteman insisted the warnings over possible industrial action were “not sabre-rattling” but said NAHT officials were “feeling the burden of pressure on behalf of our members”.

“They’ve carried that burden for so very, very long, I don’t think they’d be able to tolerate it for much more.”

Meanwhile, Teach First CEO James Toop called for “cross-government prioritisation of teacher pay” after a survey published earlier this year showed one in 10 teachers could leave the profession in the next two years.

While he acknowledged that the Department for Education is “in a really tough spot”, he told The Independent that ministers need to put in place a “more comprehensive strategy” to recruit teachers.

He said: “We need to really focus on raising the status of teaching again. From our perspective, it’s an amazing job. It’s super challenging … But when you compare starting salaries to law and accountancy, teacher starting salaries are much lower still.”

Laying out the scale of the problem facing schools, Aidan Sadgrove, CEO of the Brigshaw Learning Partnership, a multi-academy trust overseeing seven schools in East Leeds, warned that the schools he runs are facing a major funding shortfall.

“We’ve seen a 0.5 per cent increase in our funding. There’s inflation running at 2.6 per cent … Quite a lot of unfunded costs have basically left us probably hundreds of thousands of pounds short, if not high tens of thousands. And we’re only seven schools, right? We’re a smaller trust.”

Matilda Browne, co-headteacher of Reach Academy Feltham and Reach Academy Hanworth Park, outside London, warned that the “pressure on the system” means some pupils risk “falling through the gaps”.

She said: “Within this quite stretched system, some of our families might be interacting with the school, and they might have appointments with health and with social care, or with SEND – and because the whole system is stretched, that feels really disjointed, and that can mean that some families and some children particularly fall through the gaps.”

Ms Browne said many schools have taken the issue of a lack of funding into their own hands, saying they “don’t feel like we can wait for the government” to provide desperately needed support.

“I’ve got children in my school now that desperately need loads of different things”, she told The Independent, explaining that they work around a lack of resources by collaborating with other schools to capitalise on expertise provided by different teachers.

Meanwhile, TUC general secretary Paul Nowak warned that the Labour government faces some tough decisions next year, not just from the public sector but also the private sector, due to pay stagnation over 14 years.

He told The Independent: “I think the government has to recognise that there’s a problem, and it’s a problem not just in the public sector. It’s right across the public and private sector. We had 14 years of effective wage stagnation under the Tories. If wages had grown in that 14 years on their normal trend prior to 2008, the average worker would be £300 a week better off.”

He warned: “Pay has got to be part of the solution next year. I think it’s not just about pay. I think it’s a much more strategic discussion with the unions about pay, but about workload, about work-life balance, about deployment of new technology.

“If I had a criticism of what the government’s done so far in health and in other parts of other key parts of our public services, it’s that even where the investment has gone in, quite often those big, strategic conversations haven’t taken place yet.”

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “Through our Plan for Change, we are restoring teaching as the highly valued profession it should be. Our recent proposals mean teacher pay would rise by almost 17 per cent across this parliament, equating to a significant real terms increase over the five years.

“Despite deeply challenging choices about public spending, mainstream school funding will rise again next year, reaching almost £51 billion, to help every child to achieve and thrive.

“We are helping schools get the best value for money on areas like energy, recruitment, and banking, so every penny is invested in delivering opportunities for young people.”