A teenage boy who lived more than 6,000 years ago was able to survive a lion attack and live for several months afterwards, a new study has suggested.

The boy, believed to be between 16-18 years old, may have been hunting when he was tackled to the ground by a lion and bitten multiple times on his head, experts said.

Archaeologists uncovered the remains of the boy in what is now Bulgaria. Remarkably, despite several holes in his skull, the study’s authors believe he lived for at least two to three months after the attack, although was likely to have become severely disabled.

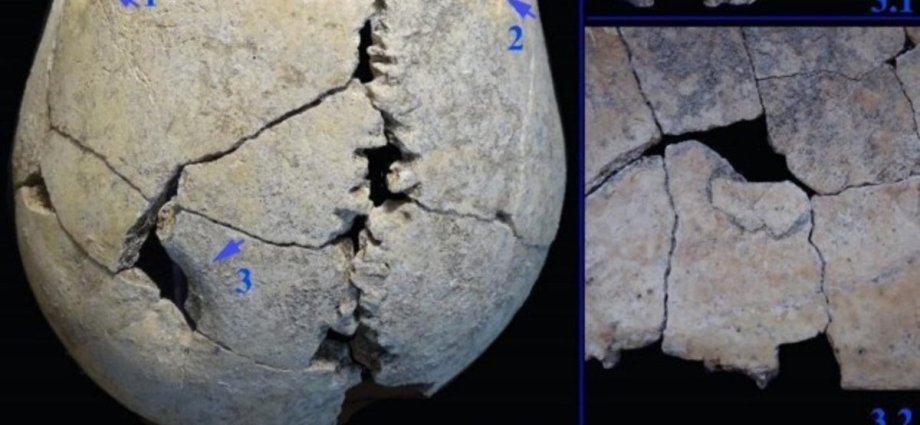

The study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, analysed two “distinct bite marks” in the youngster’s skull to uncover why and how he died.

They compared the marks with tooth imprints taken from the skulls of a number of predators, including bears and lions, to deduce the animal behind the attack. The “specific” shape of one of the marks led them to believe the boy’s skull was pierced by a lion’s carnassial tooth. A lion’s carnassial teeth are located towards the back of its mouth and are designed to tear apart meat.

Archaeological finds show lions lived in various Eastern European locations from the Neolithic period to the late Iron Age, approximately 2,000 years ago.

Scientists believe the bites may have damaged the teenager’s meninges — the membranes that line the inside of the skull — leaving the integrity of his brain in a “questionable” state which was likely to lead to severe disabilities.

Notably, their findings showed the boy survived for a period of at least two to three months after the attack, which archaeologists said “raised questions” about the “social care and community support provided to physically impaired individuals during the Eneolithic”.

“Analysis of the lesions suggests that the individual was attacked by a lion, knocked to the ground, and bitten multiple times,” the study’s authors said. “His survival and the healing of his wounds suggest that he was looked after and treated.

“According to the lesion analysis, the individual likely had difficulty walking and may have experienced brain issues. Nevertheless, he lived and was cared for by the community, indicating that they took care of their disabled members.

“This provides insights not only into the fauna and the range and behaviour of lions during the Late Eneolithic in Bulgaria but also into the social structure and status of the society that inhabited the Kozareva mound.”

It comes after bite marks found on a Roman-era skeleton in York provided the first physical evidence that humans fought animals in gladiatorial combat.

Academics said that the bones showed distinct lesions and, when compared with modern zoological teeth marks, they were identified as coming from a large cat.