A common virus that infects most people can trigger the chronic immune system condition lupus, according to a new study.

Nearly 5 million people worldwide suffer from the autoimmune disease in which a person’s immune system attacks the nuclei of their own cells.

Lupus damages organs like the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, nerves, with symptoms varying widely among individuals.

While most lupus patients can live reasonably normal lives, the autoimmune disease can be life-threatening for about 5 per cent of them. For reasons that remain unclear, nine out of 10 lupus patients are women.

Existing treatments help slow down the progression of the disease but don’t cure it.

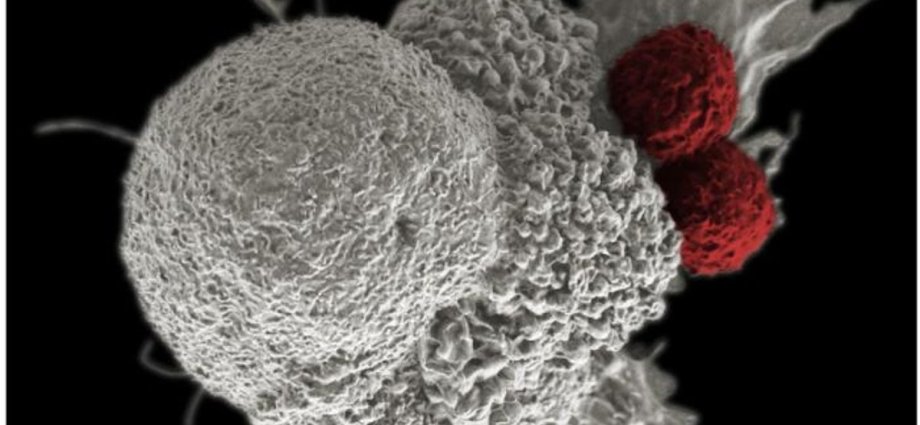

Now, Stanford University scientists say that the Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV, directly prompts a small number of immune system cells to go rogue and trigger a cascading effect whereby immune cells launch a widespread assault on the body.

“We think it applies to 100 per cent of lupus cases,” rheumatologist William Robinson said.

EBV is transmitted through saliva. It infects a vast majority of the people by adulthood, either from sharing a spoon or drinking from the same glass or maybe from exchanging a kiss.

EBV belongs to a class of viruses that are also responsible for chickenpox and herpes.

The virus deposits its genetic material into the nucleus of the infected cell. It can stay latent and hide from the immune system’s surveillance, only to spring back and infect other cells and people.

The virus is also known to cause mononucleosis, or “the kissing disease”, which starts with a fever that subsides but lapses into fatigue that can persist for months.

“Practically the only way to not get EBV is to live in a bubble. If you have lived a normal life, the odds are nearly 20 to 1 you have got it,” said Dr Robinson, one of the authors of the study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

EBV resides in only a tiny fraction of an infected person’s immune system B cells. For this reason, it’s “virtually impossible” for existing methods to identify infected B cells, researchers say.

For their latest study, the Stanford researchers developed a high-precision system to sequence and identify cells infected by EBV. They found that fewer than 1 in 10,000 of a typical EBV-infected, but otherwise healthy person’s B cells, hosted a dormant EBV virus genome.

In lupus patients, however, the fraction of EBV-infected B cells was about 1 in 400 – a 25-fold difference.

Researchers then examined how such small numbers of infected cells were triggering powerful immune attacks on one’s own tissues and organs. They found that while EBV lay in near-total inactivity, it occasionally nudged the B cells to produce a viral protein called EBNA2. The protein activated human genes behind inflammation and caused B cells to become “highly inflammatory”.

Researchers suspect this EBV-triggered self-targeting of B-cells may extend beyond lupus to other immune system disorders like multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Crohn’s disease.

It remains unclear why, if most people have latent EBV, only some develop autoimmune conditions like lupus.

Scientists speculate that only certain strains of the virus may spur the transformation of B cells into “vicious attack dogs of the immune system”.