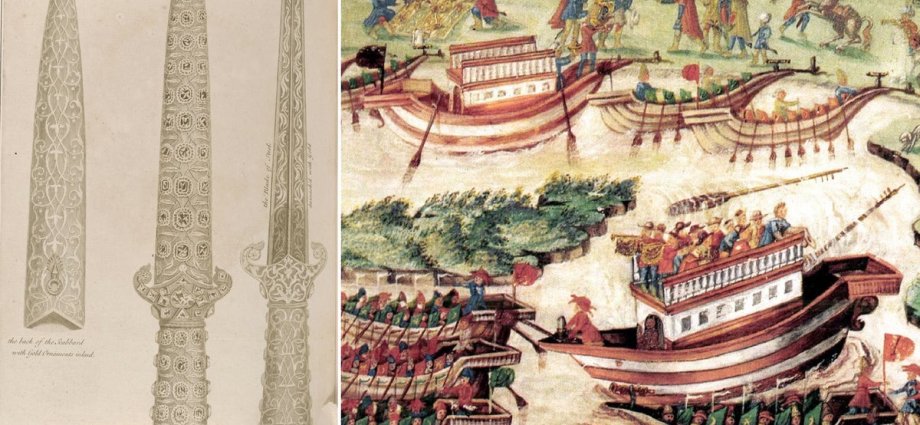

Historians have been reconstructing the long-lost story of two of British history’s most mysterious artefacts – a pair of spectacular diamond-and-ruby-encrusted gold and jade daggers. It’s one of the most detailed historical artefact biographies ever compiled in Britain.

The weapons, linked to key episodes of world history, are now the subject of a remarkable exhibition at Strawberry Hill House on the banks of the Thames in Twickenham, West London.

Investigators believe that the daggers were made in the Middle East more than four centuries ago from raw materials brought together from a series of now long-forgotten kingdoms and empires in Central Asia, India and Burma.

The jade (used to construct the daggers’ hilts and scabbards) almost certainly came from a vast Central Asian Silk Road empire known as the Khanate of Yarkent which was the size of modern India and was ruled by the descendants of Genghis Khan.

Many of the diamonds, used to adorn the jade hilts and scabbards, are thought to have probably come from a powerful yet now long-forgotten country in what is now eastern India – the Sultanate of Golconda. Approximately the size of England, it was ruled by sultans descended from the rulers of medieval Persia. But it is also possible that some of the diamonds originated as far east as Borneo which was part of the huge Bruneian empire which stretched some 2000 miles from western Indonesia to the far north of the Philippines.

The rubies almost certainly came from a major, but now long-vanished, mega-state in Southeast Asia – the Toungoo Empire (which consisted of Myanmar [Burma], Thailand, Laos and parts of north-east India and western China). Covering 600,000 square miles, it was the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia and the medieval and early modern world’s greatest source of rubies.

And, last but not least, the gold was also likely to have come from South East Asia. Some of the gold was used to adorn the daggers with short Ottoman and Persian poems glorifying the weapons.

Although the raw materials represented an almost global trade network, the daggers themselves were probably partly made in 16th century Persia (Iran) and then exported to the rulers of the Ottoman Empire, based in Constantinople (modern Istanbul) where they were further enhanced. The nephrite jade hilts and scabbards (and the gold foil decoration on them) appear to have been crafted in Persia (or, alternatively, by Persian craftsmen in Constantinople) – while the steel blades (and the precious gems on the hilts and scabbards) represented a more Ottoman style, and were therefore added in Constantinople.

Investigators, at (and working in conjunction with) Strawberry Hill House, have also succeeded in reconstructing how the jewel-encrusted weapons made their way from Constantinople to England.

One leading possibility is that they were given by the Ottoman Sultan, Ahmed I as a diplomatic gift to the Prague-based Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II, as part of a peace treaty signed in 1606, which brought to an end, a bitter 13 year long war between the two empires.

Then, 30 years later the Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand II, appears to have given them to one of King Charles I’s top diplomats, an ultra-wealthy English aristocrat and art collector by the name of Thomas, Earl of Arundel.

But Thomas’s heirs passed the weapons to two other art-collecting aristocrats – the English philanthropist, Elizabeth Germain and the nobleman and property developer, Edward Harley, Earl of Oxford (after whom London’s Oxford Street is named).

Then in the 1770s, the British prime minister’s son, art enthusiast Horace Walpole, bought the dagger in Germain’s collection from her heirs and exhibited it in his beautiful Thames-side home – Strawberry Hill.

But, the weapon was about to experience a major change of lifestyle – for, in 1842, one of Victorian England’s top Shakespearean actors, Charles Kean, bought the glittering gem-studded dagger and used it as a prop to enhance his performances – partly because tradition erroneously maintained that the weapon had originally belonged to England’s most famous Tudor king, Henry VIII.

But, years after Kean died, his daughter sold it in the 1890s at auction to an American multi-millionaire, Waldorf Astor who subsequently installed it in his newly-acquired English stately home, Hever castle in Kent (the former home of Queen Anne Boleyn [executed by Henry VIII] and of Anne of Cleaves, also formerly married to Henry). The weapon’s new owner, Waldorf Astor became an English baron in 1916.

However, Hever was destined to be the dagger’s last known home – for it was stolen in a daring heist in 1946, widely believed to have been committed by another aristocrat, Victor Hervey, Marquess of Bristol, an Eton-educated convicted criminal known as the Pink Panther who led a jewellery-stealing gang, known as the “Mayfair Playboys”.

Art crime experts think it likely that the historic jewel-encrusted jade and gold weapon ended up in a private collection somewhere in the USA but nobody knows for sure.

However, the dagger’s former home Strawberry Hill House (where the current exhibition about the weapons is being held) is now appealing to art collectors and others worldwide to let them know if they have any information about the fate or whereabouts of the vanished dagger.

The fate of the two daggers had diverged dramatically. Its twin, which was acquired by Edward Harley, Earl of Oxford in the early 18th century, is still normally in what was his stately home, Welbeck Abbey, Nottinghamshire, but is currently on display in the Strawberry Hill exhibition in Twickenham. However, its probable diamonds and rubies had, at some stage, been removed and replaced by less valuable gems, namely garnets.

Now the search is on for the stolen Walpole dagger and scabbard, which at the time they were stolen from Hever Castle in 1946, still had all their rubies and diamonds, including some relatively large ones.

“We now hope that our appeal for information about the stolen dagger will yield information about its history since 1946 – and its whereabouts today,” said Strawberry Hill’s Senior Curator, Dr Silvia Davoli who led the investigation into both daggers’ extraordinary history.

The Strawberry Hill exhibition, Henry VIII’s Lost Dagger: From the Tudor Court to the Victorian Stage, will run until Sunday, 15 February.