Researchers have unearthed strong evidence of thousands of Black Death victims in a first-of-its-kind mass grave at a medieval village outside Germany.

The find marks the first systematically identified burial site associated with plague victims in Europe.

Between 1346 and 1353, the Black Death plague pandemic wiped out nearly half the population in some parts of the continent.

Written records indicated that about 12,000 people were buried in large pits outside the city of Erfurt, but their exact locations had remained unknown.

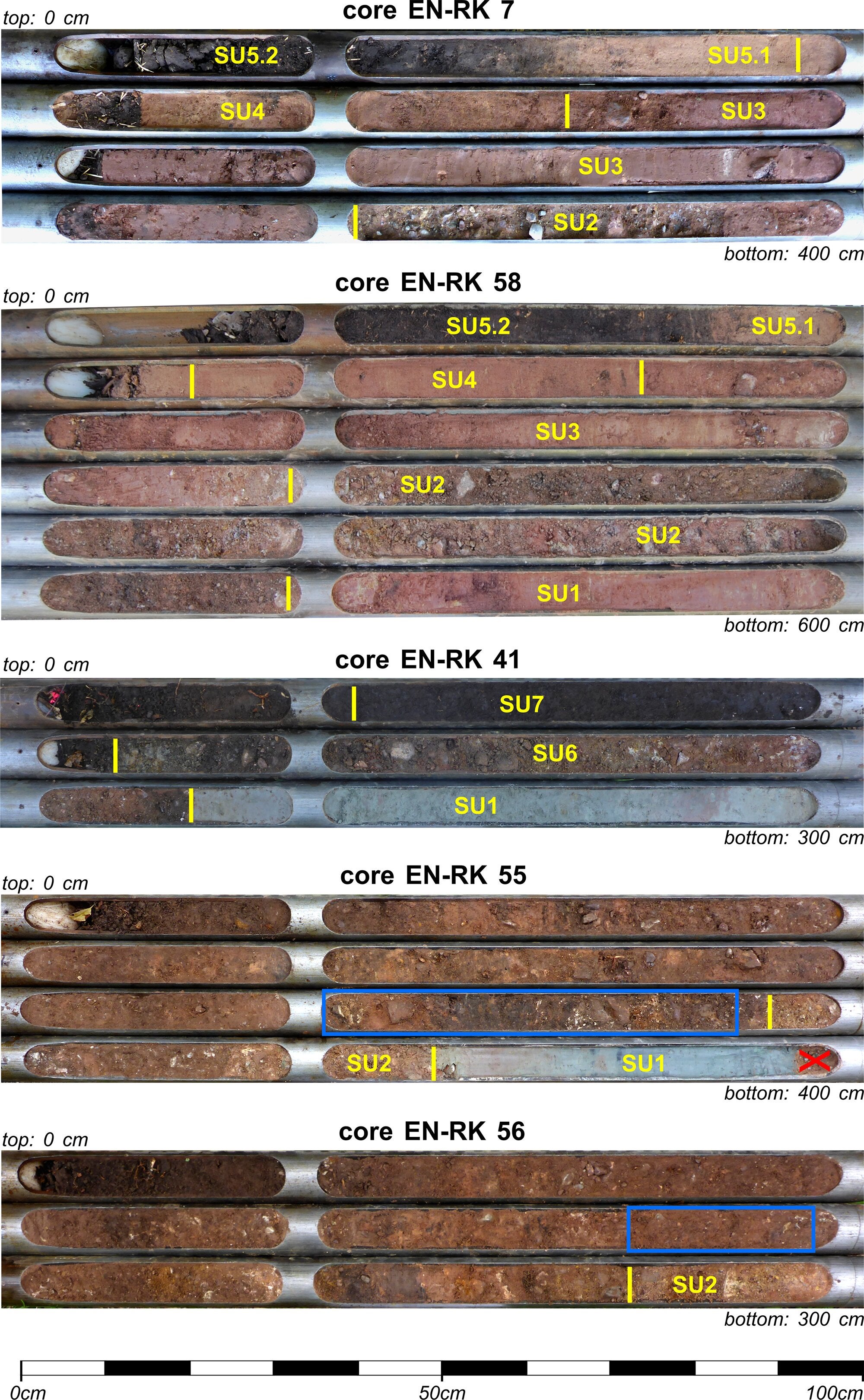

Now, an interdisciplinary research team assessed historical sources, land measurements, and sediment cores to identify a burial structure corresponding to the plague pits described in 14th-century written records.

“Our results strongly suggest that we have pinpointed one of the plague mass graves described in the Erfurt chronicles,” geographer Michael Hein from Leipzig University said.

“Definitive confirmation, however, will only be possible through planned archaeological excavation,” said Dr Hein, author of the study published in the journal PLOS One.

-and-Dr-Michael-Hein-(right)-carry-out-sediment-coring-to-locate-a.jpeg)

The analysis of scientists, who tried to reconstruct the medieval land surface, revealed a large subsurface structure near the deserted medieval village of Neuses, outside Erfurt.

Excavations revealed that the structure contained fragments of human remains dated clearly to the 14th century.

“A major achievement of this study is that the find was made through an interdisciplinary prospection approach combining historical research with natural science methods, rather than through accidental discovery,” said Ulrike Werban, another author of the study from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research.

In medieval times, this mass burial was likely made at the village’s drier chernozem zone – or black soil rich in carbonates and humus – along the valley edge of the River Gera, researchers say. Wetter floodplain soils were generally avoided for burials at the time, as bodies decomposed more slowly in such conditions.

This aligns with the “miasma theory” that people believed in medieval times, which held that diseases spread through “bad air” and “vapours” from decaying organic matter.

“By linking historical, geophysical, and pedological methods, we were able to read the landscape as an archive,” Dr Hein said.

The finding is significant as confirmed and precisely dated Black Death mass graves remain exceedingly rare, with fewer than ten known across Europe.

Further research at the site could shed light on the evolution of the plague pathogen, Yersinia pestis, the causes of the high mortality in the mid-14th century, and how societies coped with epidemics.

“….our systematic discovery of a possible plague pit may help to advance the research on the origin, spread and evolution of the Yersinia pestis pathogen (that causes plague),” scientists wrote.

Researchers hope the study could help systematically discover more such medieval burial sites.

“This discovery is not only of archaeological and historical importance,” says Christoph Zielhofer, another author of the study from Leipzig University.

“It helps us to understand how societies deal with mass mortality – and how modern interdisciplinary science can contribute to locating mass graves, topics that remain relevant even in the 21st century,” Dr Zielhofer said.