Peculiar 60,000-year-old Stone Age arrowheads unearthed in South Africa could be the earliest known use of poison-laced weapons by human hunters, archaeologists say in a new study.

For long, researchers have attempted to trace the trajectory of innovations by prehistoric humans to better understand the evolution of hunting technology.

One such innovation is the use of poisoned weapons, which are seen as a hallmark of advanced hunter-gatherer technology.

Until now, the evidence of poisoned hunting tools has been sparse, mostly dating to the last Ice Age around 10,000 years ago.

Scientists have now identified traces of poison from the South African plant gifbol on arrowheads dating to about 60,000 years ago, making it the oldest known arrow poison in the world to date.

The findings reveal that prehistoric people in southern Africa had already developed advanced knowledge of toxic substances and how they could be used for hunting.

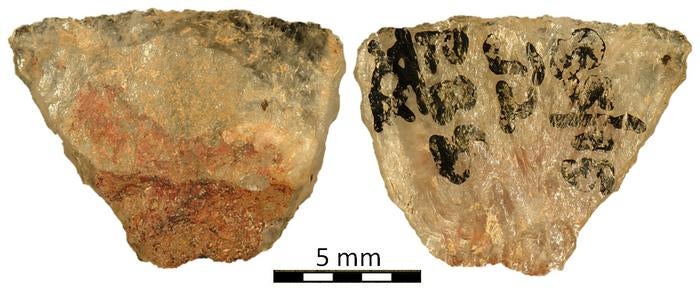

Researchers unearthed old quartz arrowheads from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and identified chemical residues of poison from the plant gifbol, which is still used by traditional hunters in the region.

“This is the oldest direct evidence that humans used arrow poison,” says archaeologist Marlize Lombard from the University of Johannesburg.

“It shows that our ancestors in southern Africa not only invented the bow and arrow much earlier than previously thought, but also understood how to use nature’s chemistry to increase hunting efficiency,” says Dr Lombard, an author of the study published in the journal Science Advances.

In the study, scientists conducted chemical analysis of the prehistoric arrowheads.

They found the presence of the poisonous plant compounds buphanidrine and epibuphanisine.

Researchers found similar substances on 250-year-old arrowheads in Swedish collections, which were collected from the region by travellers during the 18th century.

“By carefully studying the chemical structure of the substances and thus drawing conclusions about their properties, we were able to determine that these particular substances are stable enough to survive this long in the ground,” said Sven Isaksson, an author of the study from Stockholm University.

Together, these findings indicate there has been a long continuity of knowledge about the poisonous plant.

“Finding traces of the same poison on both prehistoric and historical arrowheads was crucial,” Dr Isaksson said.

“It’s also fascinating that people had such a deep and long-standing understanding of the use of plants,” he added.

The study shows that prehistoric hunters of the region not only had the technical skills to make such arrowheads, but also advanced planning abilities and an understanding of how poisons work over time, characteristics indicative of modern human cognition.

“Using arrow poison requires planning, patience and an understanding of cause and effect. It is a clear sign of advanced thinking in early humans,” said Anders Högberg, another author of the study from Sweden’s Linnaeus University.