“It was one of those kind of serendipitous occasions – a Eureka moment,” says Professor Richard Bevins.

Picking over a set of 15 sample stones from Stonehenge passed on to him by a former colleague, the experienced geologist was asked to make a quick observation on the source of rock believed to have been brought from west Wales some 5,000 years ago.

“I said I can tell you what they are in terms of rock type, but this rock type – I’ve never seen in west Wales, never seen it at all,” Prof Bevins recalls. “So I wrote it up [his report], but before it was published, I had a Eureka moment and thought ‘there’s an outcrop that I have got material from but that I’ve never looked at before’.

“It led to the excavation of a Neolithic quarry [Craig Rhos-y-Felin] and the discovery of the exact location where the stone samples came. A perfect match. It was a special moment.”

That major discovery in 2011 was the first time a definite source for any of the stones for the world-famous monument had been found, reinvigorating the long-running debate on how the stones were transported all the way from Pembrokeshire to Wiltshire.

Now, today, 14 years on, Prof Bevins believes he could be on the verge of his next ground-breaking find; the source of the monument’s Altar Stone.

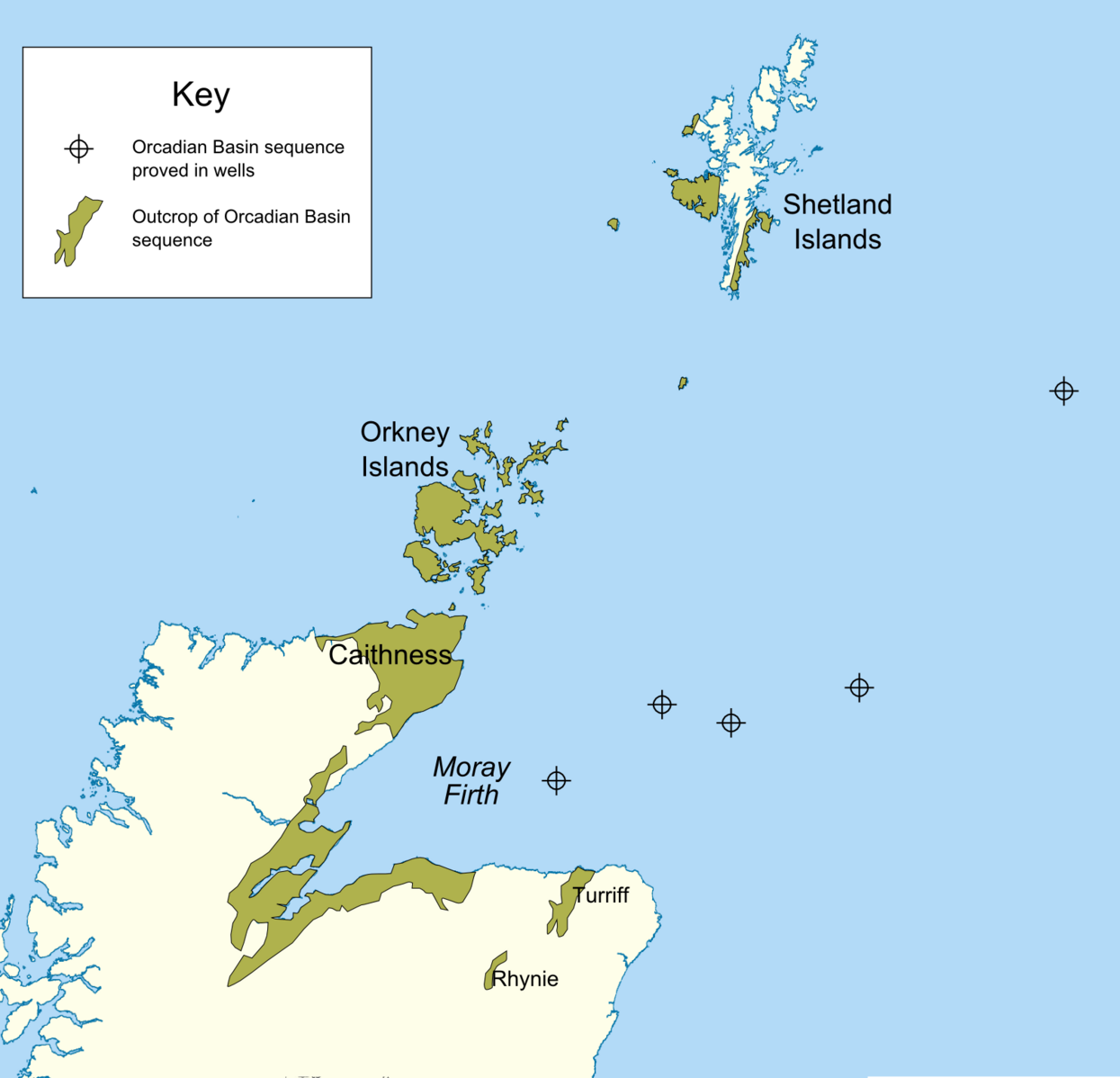

Having declared that the six-tonne megalith was not one of the bluestones hauled from Pembrokeshire last year, he and his team ventured to the archipelago of Orkney after determining it came from sandstone deposits in the Orcadian Basin, an area encompassing the isles of Orkney and Shetland and a coastal strip on the north-east Scottish mainland.

Detailed study of the stones in Orkney, however, came up with no match – and now Prof Bevins is staring at a mapped area 125 miles by 93 miles, determined to discover the exact location the stone was quarried, before being transported more than 500 miles to the West Country.

“It’d be fantastic to find the exact source,” Prof Bevins says. “It’s been a rollercoaster to get this far, having found it doesn’t come from Wales but now from north-east Scotland. It’d certainly be the icing on the cake for all the work we’ve put in.”

Finding the source would open excavation works for archaeologists at the source site, who would then be able to trace the people behind the construction of Stonehenge and find out everything from their society to their tools to what they ate and drank.

It would also, Prof Bevins says, add more substance to the theories behind how the huge stones were moved the hundreds of miles, with current thoughts, due to the hilly landscape in Scotland, that it was instead moved by sea.

.jpeg)

The discovery of the location could also strengthen research that the building of Stonehenge was an act of unification across the UK against a foreign threat, with materials coming from all corners of the British Isles.

But for now, Prof Bevins says he needs to work with his small team to pinpoint locations within the huge region.

“If we just went up there and went randomly walking across the whole area, we’ll probably retire and be a long time underground before anything were found, so we’ll be picking out some target areas within that region,” says Prof Bevins.

But it takes time, and operating in the field is expensive and time-consuming.

And after funding finished on ruling out Orkney last year, Prof Bevins and his team need to build a new case for money to pay for the next part of their project. Part of their case will be the public’s thirst for information on one of the UK’s most famous monuments, Stonehenge, which had a record 1.4m visitors in 2024.

“People like to know about other people, they like to know about their history, they like to know why Stonehenge built, what do the pyramids mean? It’s that fascination with people and cultures,” says Prof Bevins.

“When we publish a paper [on Stonehenge] you can almost clock it going around the world across time zones. News, television channels, online. It really is quite astonishing. We’re hoping to achieve the same results again soon.”