Fifteen years ago, Arri Coomarasamy was invited by a friend to spend a couple of weeks in Malawi. The then-38-year-old was training to be an IVF doctor and made plans to visit a local hospital.

“I remember going into the room, which was in fact the mortuary, and there were three dead women,” he says. Two had died of the same cause: they had bled to death after giving birth. “I guess what I saw in that room has never really left me in my professional life“.

It started him on a journey to understand why so many women in poorer countries were dying from postpartum haemorrhage, or excessive bleeding after childbirth, which remains the leading cause of maternal deaths around the world.

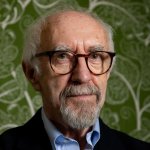

Research, spearheaded by now Professor Coomarasamy and the University of Birmingham, discovered a way of stopping 60 per cent of cases of deadly bleeding – thanks to a mixture of better diagnosis, medication and training. However, key US-funded programmes that had just started to bring that knowledge to patients have been slashed in size, meaning it has been stopped from reaching thousands of women.

Despite repeated claims by US officials to protect lifesaving work, following Donald Trump’s slashing of foreign at the start of 2025, a plan was put in motion to cancel one such programme, called Momentum Country and Global Leadership, in more than 10 out of roughly 25 countries where it previously operated. Dedicated to getting healthcare to pregnant women and children, it has been curtailed in some of the poorest countries with the highest maternal mortality, The Independent has learnt.

One aspect of the approach involves teaching midwives and doctors best practice on how to reduce cases of haemorrhage. Several insiders connected to the work have told The Independent that cuts to a range of programmes mean this life-saving opportunity will now not make into a number of clinics. “There is no doubt in my mind that the cuts have massively impacted the rollout of [the approach] and other similar effective interventions, which are life-saving,” Coomarasamy, now an Oxford professor of reproductive medicine, says.

A US State Department spokesperson said: “The Trump Administration remains committed to saving lives and improving maternal health outcomes globally. Under the America First Global Health Strategy announced in September 2025, we are prioritising direct investments in frontline healthcare workers and essential health commodities—including those that prevent maternal mortality—while eliminating wasteful overhead and ensuring US assistance builds sustainable, locally-led health systems”.

‘A medical scandal’

Women in rich countries have a similar chance of facing haemorrhage as those living in poorer nations. “What differs is the likelihood of you dying,” Coomarasamy explains. “What you start to realise quite quickly is that a woman doesn’t need to die from postpartum haemorrhage”.

He had discovered what he considers to be a “medical scandal”: half of all cases of life-threatening bleeding were going undiagnosed.

The first problem was that health workers were not very good at recognising by sight when a woman was losing too much blood and were diagnosing dangerous cases too late.

Secondly, even once excessive bleeding was identified, it was taking too long to give patients a treatment that worked. Hospitals had been trying one treatment and waiting to see if it worked before moving on to the next one – a common approach in medicine, but a risky one when someone is bleeding heavily and time is of the essence.

“We realised that what kills the woman when she bleeds is really the ticking clock,” Coomarasamy says.

“The more that the time passes from the moment that the woman starts to bleed, the greater the blood loss,” and the greater the chances she will need more intensive treatment or will lose her life.

While in richer countries, women have the safety nets of surgery, blood transfusions and intensive care, in lower-income countries they don’t reliably have these options.

The breakthrough came in 2023. As part of a trial, the team introduced into clinics a plastic blood-collection device known as a drape, placed under a patient during birth to more accurately measure how much they are bleeding, and identify faster if they are losing dangerous amounts. And they experimented with giving all the different types of treatment we already know to be effective at the same time: oxytocin to contract the uterus; tranexamic acid to clot the blood; an IV drip to replace fluids.

The results were transformative; together this simple approach reduced severe bleeding, surgeries and deaths by 60 per cent – an extraordinary finding in modern medicine.

Coomarasamy realised partway through the trial that something different was happening when he visited clinics in the trial countries. Health workers would collar him and frantically ask how they were going to get the drapes and drugs once the research finished.

“They would tell me…‘it definitely works, we’ve not had any women dying. You know we normally have two, three bags of emergency blood in our fridge – it hasn’t been touched’”.

Now the research just needed to reach patients. It’s this work that has stumbled in a number of countries in recent months since the US cuts were announced.

‘We are putting lives of women and newborns at risk’

In Malawi, where Coomarasamy had the revelation that started him on this path some decade-and-a-half ago, the consequences seem to be already playing out.

Nurse Victoria Mzungu remembers one birth particularly clearly. A woman had delivered twins prematurely on her way to the hospital, and was bleeding heavily. She arrived pale and struggling for air as the proteins in her blood responsible for getting oxygen to her cells plummeted. The team rushed to give her all the treatment they had at their disposal, and the woman survived.

Mzungu puts the woman’s survival down to the new training. In the three clinics in in her district of Salima where the approach had been introduced so far, no maternal deaths from bleeding have been registered this year.

But since the US funding was ended in certain areas, they haven’t had access to key drugs and equipment including the drapes. “We haven’t stopped,” she says, but the team is left trying to use the approach without those crucial ingredients, “using the available resources… on the ground.”

The rate of pregnant women in the district attending a minimum of four antenatal visits has fallen from 41 per cent to 36 per cent since January. That in turn has hit the numbers of women getting important supplements like iron – which can reduce the risk of death from bleeding in childbirth.

It’s largely down to the cancellation of outreach programmes designed to get medical care to remote communities, where people live 30km or more from their nearest health facility. This means, “a pregnant woman has to walk once every month for nine months for antenatal services,” says Hester Nyasulu, Malawi country manager at charity Amref. “She has to brave that 30 kilometres. Now, if it’s in the eighth month,” he says, “that’s not an easy thing.”

As a result, women are missing scheduled antenatal visits, “so already we are putting lives of women and newborns at risk,” he says, and risking reversing gains made in recent years.

In poorer countries, women are more likely to start their pregnancies with nutritional deficiencies which raise their chances of getting very sick if they do haemorrhage, making this kind of prevention all the more important.

Two hours north of Salima, in Nkhotakota district, clinics lost track of 900 pregnant women and recorded more than 2,000 fewer antenatal visits after the US cuts. Cases of excessive bleeding have jumped back up to where they were when a US-funded programme started in 2022, having halved in that time. An audit report seen by The Independent found a woman who died from haemorrhage could have survived if the cuts hadn’t taken place, causing gaps in knowledge and equipment including surgical garments to stop bleeding.

Another strand of the US-funded work, run by WaterAid, was making sure maternity wards had clean water and toilet facilities, including in Salima. This too has been stopped, resulting in a fall in women attending the clinics, the charity says, because they know they will face unhygienic and “dehumanising” facilities.

A State Department spokesperson said the US was currently providing nearly $12m to Malawi for maternal, newborn and child health.

‘I feel like we’re going back 20 years’

After Trump’s stop work order initially froze all foreign aid spending overnight, US programmes on maternal health were cancelled and resurrected several times, causing confusion. Now the dust has settled, former and current employees carrying out US-funded maternal health programmes have told The Independent that the cuts mean, “there’s just not the same support” for making sure facilities have everything they need to treat deadly bleeding”, says postpartum haemorrhage expert Cherrie Evans, and that plans to scale the training up have “stalled” in a number of places.

“You can have the best intervention but if you can’t get it implemented with the medicines, supplies, and skilled workers you need, it doesn’t matter,” she says. “I feel like we’re going back 20 years in the programming we’re being asked to do”. This will particularly impact countries like Tanzania with less robust health systems which were not as far advanced in introducing some of the new knowledge around tackling bleeding.

Part of the reason this work was only just getting started, insiders and experts agree, is the wider neglect of maternal health, which is often not seen as an emergency by governments. Diseases like HIV or malaria have had comprehensive programmes dedicated to tackling them with drugs and prevention. Though major gains have been made on maternal health in recent decades, progress has been slower.

“People have always said, and it’s absolutely true, that if you can manage to solve the problems of maternal health, you will have solved many of the key health system problems,” says Deborah Armbruster, formerly a senior maternal and newborn health advisor for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Efforts to get the new approach to tackling haemorrhage into clinics were, “very nascent,” a clinician who did not want to be named says, with work “just barely getting started”.

In its new form, it is not only reaching roughly half as many countries, but now comes with the condition from the US State Department that it can only focus on “lifesaving interventions,” including medications – but excluding any mention of gender or family planning – Suzanne Stalls, a leading nurse-midwife previously affiliated with the programme explains.

She says that this is the same type of work that has been going on for 25 years and, while important, that medical staff have “learned it wasn’t enough” to reliably save mothers lives.

“Diagnosis is fundamental in medicine,” Professor Coomarasamy says. “You can have the perfect treatment,” he adds, but if there aren’t things in place to make sure that patients both make it into clinics and have access to a test that picks up the condition, “you’re not going to be able to use this perfect treatment”.

This article has been produced as part of The Independent’s Rethinking Global Aid project