Giant “dragon stones” found across the Armenian highlands were shaped and installed by an ancient “water cult”, archaeologists revealed in a new study.

The pillar stones carved in animal shapes and dating to over 6,000 years ago are found across the mountainous regions of Armenia and neighbouring countries. They predate the Stonehenge megalithic structure in England by almost a thousand years.

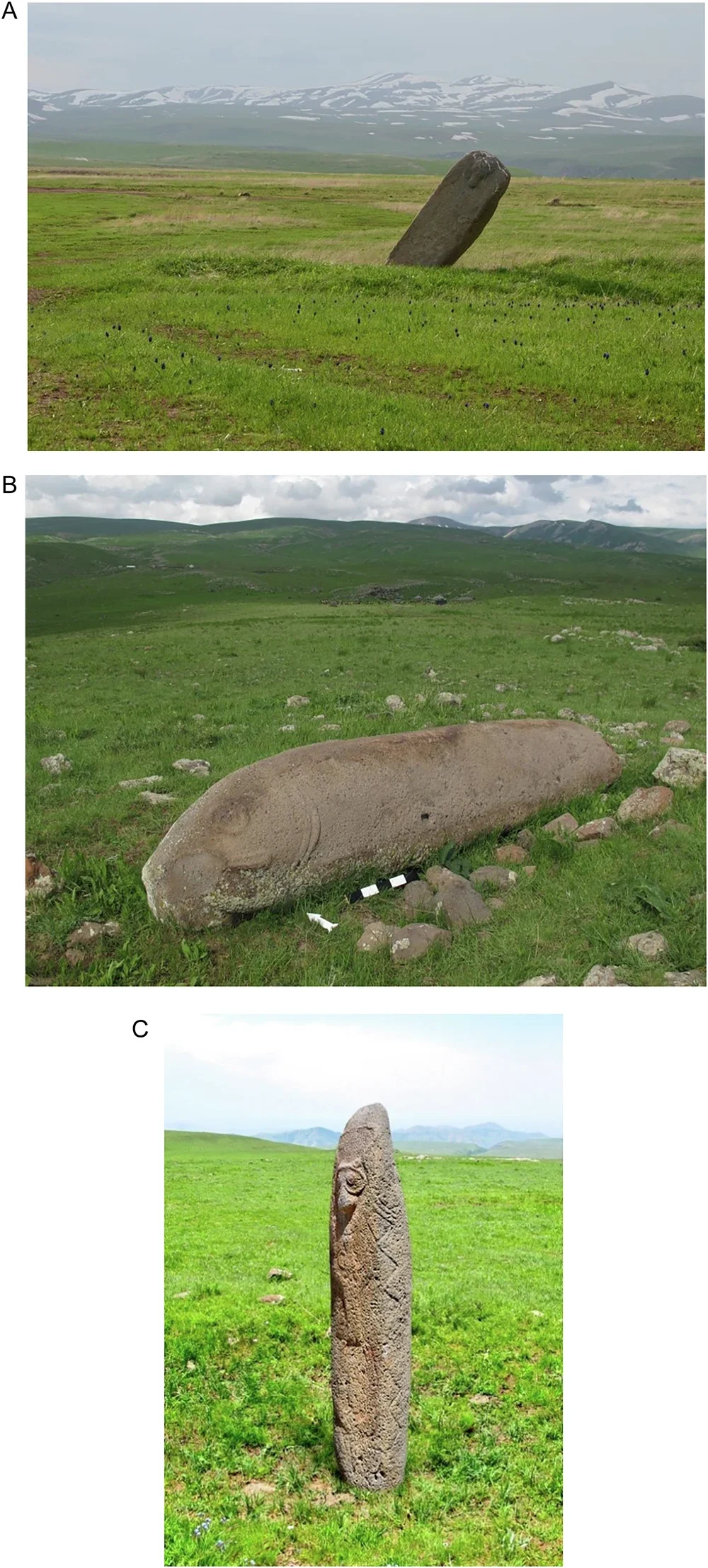

The pillars, locally known as vishaps, measure between 1.1m and 5.5m tall. They are carved from local stones such as andesite or basalt and can be found at elevations of 1,000m to 3,000m above sea level.

It remains a mystery how ancient inhabitants of the region dragged the pillars through such harsh terrain and set them upright.

But a first systematic analysis of the pillars across the Armenian highlands does offer an insight into the people who installed them.

Researchers used GIS mapping, 3D modelling and statistical tools to analyse as many as 115 vishaps across the highlands and their distribution and found clear patterns in how the monuments were placed.

The pillars came in the shape of a fish or a stretched cattle hide or a hybrid form combining the motifs. This and the finding that most of the pillars are near water sources like hot springs, old irrigation systems, snowmelt streams, or volcanic craters suggests the builders were likely part of a cult centred on water as a life source.

“The findings support the hypothesis that vishaps were closely associated with an ancient water cult as they are predominantly situated near water sources, such as high-altitude springs and discovered prehistoric irrigation systems,” researchers noted in a study published in the journal NPJ Heritage Science.

Even the elevations at which the pillars are found aren’t random. Researchers found the pillar stones clustered into two altitude bands, one around 1,900m and the other 2,700m above sea level.

Building and moving the stones higher up would have required extra effort, so the monument must have carried a strong cultural or religious meaning to the ancient people, they reasoned.

Scientists suspect this distribution is a reflection of different environmental zones in the highlands and the seasonal movement of people through the mountains seeking pasturelands.

For instance, fish-shaped stones dominate the highest elevations, near natural springs fed by melting snow, and the hide-shaped stones are seen lower down, where water is used for farming.

“The unexpected bimodal distribution of their altitudes suggests specific placement patterns, potentially linked to seasonal human activities or ritual practices,” the new study notes.