Being identified as a child prodigy could actually hamper the chances of being a high performer later in life, a new study has found.

Researchers looking at the development of world-class performers in science, classical music, chess, and sport, concluded that high-flyers do not necessarily develop as child prodigies – and that the best youths and later world-class performers don’t always start life as high-flyers.

The study from a team led by Professor Arne Güllich, professor of sports science at RPTU University of Kaiserslautern-Landau, was published in journal Science and concluded that exceptional young performers reached their peak quickly, but rarely mastered in one interest.

By contrast, exceptional adults reached peak performance gradually with broader, multi-disciplinary practice.

The team examined the development of 34,839 international top performers, including Olympians and Nobel prize winners, finding they tended to undergo a different pattern of development than was previously assumed.

The study said traditional research had believed that the key factors in becoming an outstanding performer were early performance, corresponding ability and years of training, with talent programmes often focussing on top-performing young people and honing their skills in one particular field.

It gives rise to the popular cultural idea of the child prodigy – whether it’s footage of an eight-year-old Lionel Messi running rings around defenders in a youth tournament or the prodigiously talented young Mozart, performing concerts as a teenager.

But Professor Güllich’s work called into question that such an idea is universal, suggesting it can do more harm than good. He warned that making young prospects focus on a single discipline may actually harm their chances of progression.

He said: “Traditional research into giftedness and expertise did not sufficiently consider the question of how world-class performers at peak performance age developed in their early years.”

The study made three key findings, the first being that the best performers at a young age and the best later in life are mostly different individuals.

Second, those who reached the world-class level showed rather gradual performance development in their early years and were not yet among the best of their age group.

The third finding was that those who later achieved peak performance did not specialise in a single discipline at an early age, but engaged in various disciplines, be it different subjects of study, genres of music, sports, or professions. Specialising later in life is a better route to success, according to the study.

This led to hypotheses posed by the researchers; that varied learning experiences in different disciplines enhance your ability to learn, improving subsequent ongoing learning at the highest level in a discipline.

It also suggests that engagement in several disciplines mitigates risks of career-hampering factors, such as burnout, losing love for the field, or injuries.

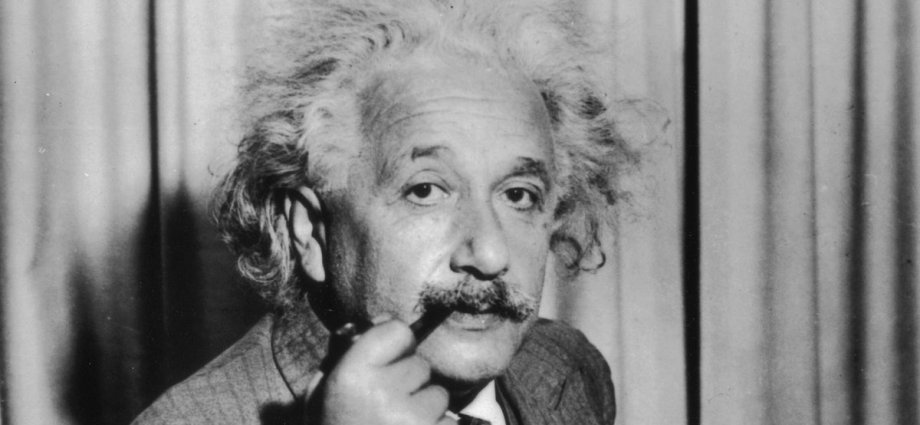

Albert Einstein was cited by the study. He became one of the world’s most influential and important physicists but he was a passionate violin player from a young age.

In a word of advice, Professor Güllich said: “Don’t specialise in just one discipline too early. Encourage young people and provide them opportunities to pursue different areas of interest. And promote them in two or three disciplines.”