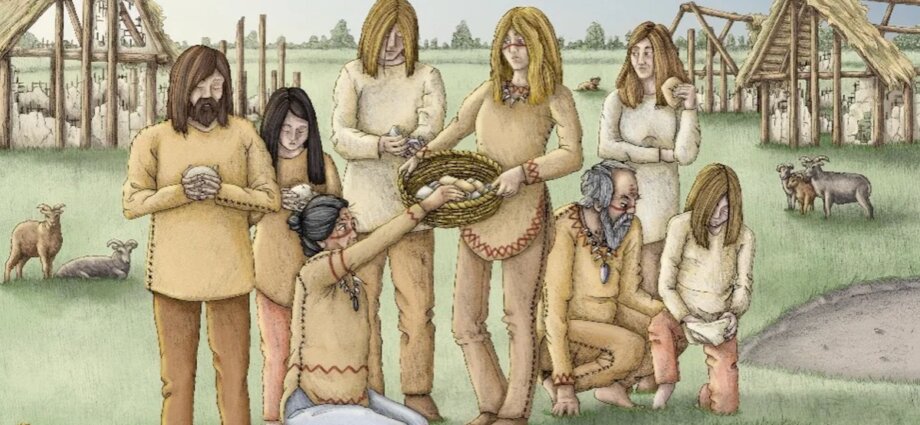

Archaeologists have found a cache of over a dozen broken human skulls at a Stone Age village site in Italy, a discovery that could advance our understanding of how ancient humans related to their ancestors.

Stone Age people at Masseria Candelaro in Puglia, Italy, deposited broken skull and jaw bones from about 15 individuals in a pile at the centre of the village, researchers found.

The bones were found heaped in a prehistoric building at the excavation site, which was a small village surrounded by concentric ditches dating to 5500–5400BC.

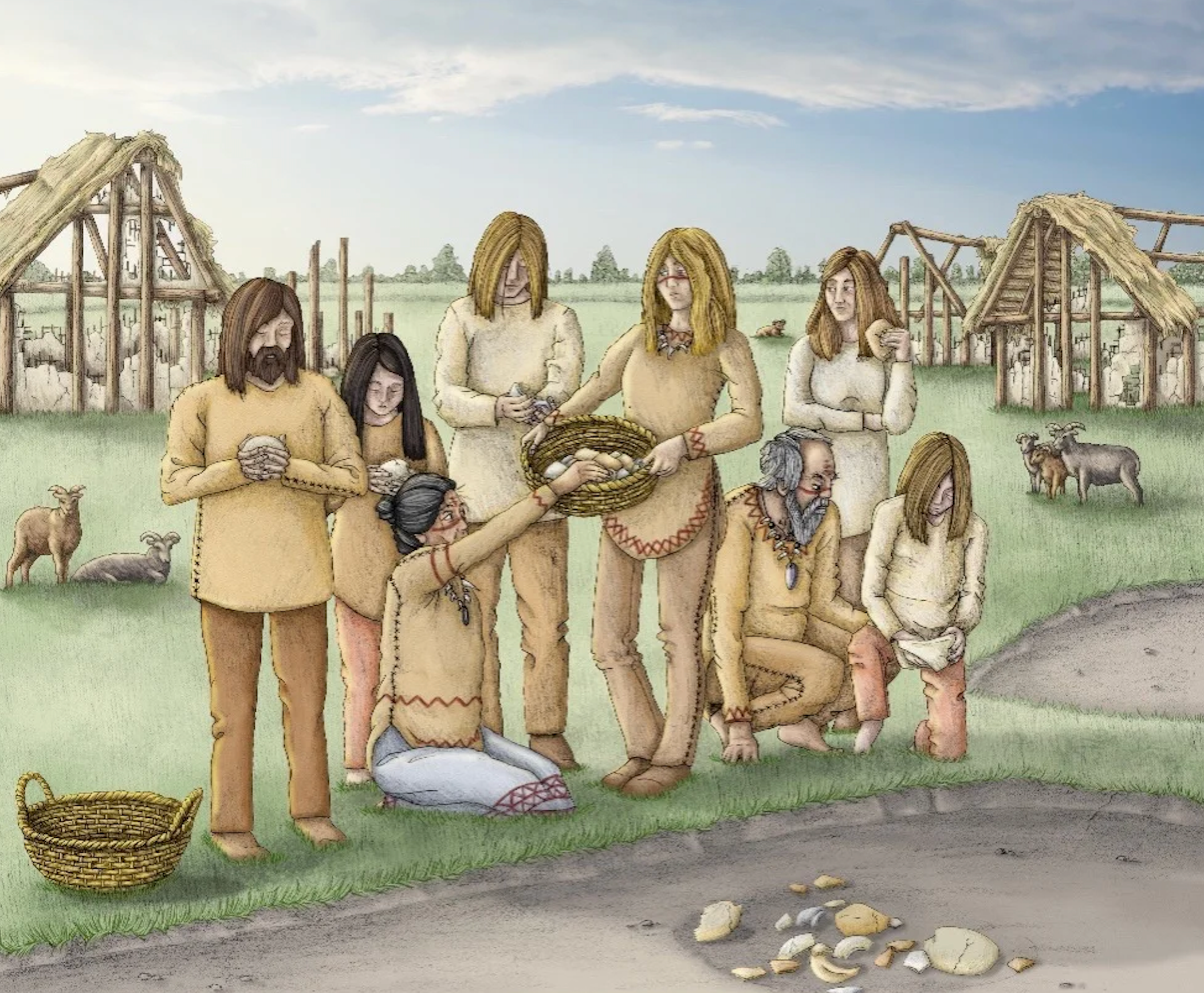

Decreeing a deceased individual as an “ancestor” was often closely tied to kinship, reflecting on the social force or presence they held among the living.

Individuals hailed as ancestors were believed to hold spiritual powers and functioned as moral anchors in several ancient cultures, researchers said.

The skull fragments found in Italy were likely linked to rituals directed towards specific ancestors as opposed to standard funerary rites.

“The ontological transformation of a dead person into an ancestor is almost always accomplished by transforming their physical remains,” researchers said.

In the latest study, published in the European Journal of Archaeology, researchers excavated a structure in the village, labelled Structure Q, with layers of domestic and ritual artefacts.

They said it was the earliest known settlement area at Masseria Candelaro but post-dated its occupation by half a millennium.

It was found to have a sunken feature containing alternating deposits of domestic and ritual materials and one of the top layers contained skull fragments, mostly belonging to males, with soil covering them.

“Structure Q was thus probably a multi-functional space later repurposed for ritual activities,” researchers said.

Analysis of the skulls dated them to between 5618 and 5335BC, and the bone fragments showed no signs of mortal injuries or healed trauma.

Based on these findings, researchers concluded that the bones belonged to individuals who lived across centuries, “perhaps six to eight generations”.

“The cranial cache represents a collection that was constantly changing but its long duration suggests an enduring tradition of use, alteration, and augmentation,” they wrote.

The skulls did not bear any cut marks showing signs of violence, indicating they were not collected as trophies of war but used in a ritual.

The final burial of the bones, researchers said, was likely not part of the ritual “but rather a simple post-use-life decommissioning”.

“These individuals were mostly probable males, collected over two centuries and actively used, with their deposition marking the final disposal of a ritual collection,” they wrote.