Chinese researchers have invented a new gel that could better protect wood from historic shipwrecks from the dangers of erosion.

The hydrogel, which is made of water and other synthetic substances known as polymers, melts into the artifacts and works to neutralize elements that could harm the waterlogged material, including wood-eating fungi and acid-producing bacteria. Hydrogels are also used in medicine and firefighting.

“The gels can be stretched to 20 times their initial length and demonstrate a 99 percent reduction in bacterial presence,” the researchers said. “This innovative hydrogel effectively neutralizes the acid generated by bacteria metabolism and notably possesses self-dissolution behavior that avoids the damage caused by peeling off the hydrogel from the wood surface.”

Researchers said the goo’s characteristics “provide a distinct advantage for the timely protection and multipurpose preservation of wooden artifacts and offer potential in other comparable scenarios.”

The gel was the result of a collaboration between multiple institutions, including Guangdong’s Sun-Yat Sen university and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Their findings were published recently in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

The Royal Society of Chemistry says that state of a shipwreck depends on several factors, including how long it was underwater its materials, and the conditions where the ship sank. For example, the SS Endurance, the vessel of explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton that had been lost since 1915, was well-preserved 10,000 feet below the surface of the extremely cold Antarctic Weddell Sea when it was found more than a century later.

To help keep the history alive, conservators slowly dry marine wooden artifacts to preserve them. They utilize a process that replaces the water with highly pressurized carbon dioxide or a viscous polymer. They can also freeze-dry the artifacts. These efforts take months and can inflict damage, according to the American Chemical Society. The wood can become brittle or warped.

Nearly two decades ago, scientists found that the production of sulphuric acid inside the ship wood could be the cause of chemical and physical damage. Scientists said a year later that iron from the Swedish warship Vasa, located at the bottom of Stockholm’s harbor, was causing its degradation.

“Upon recovery and exposure to air, waterlogged wood undergoes substantial drying shrinkage and deformation. As a result, marine waterlogged archaeological wood preserved in museums becomes more sensitive to changes in humidity,” researchers from Beijing and Quanzhou said in a separate study published in the Journal of Cultural Heritage earlier this year.

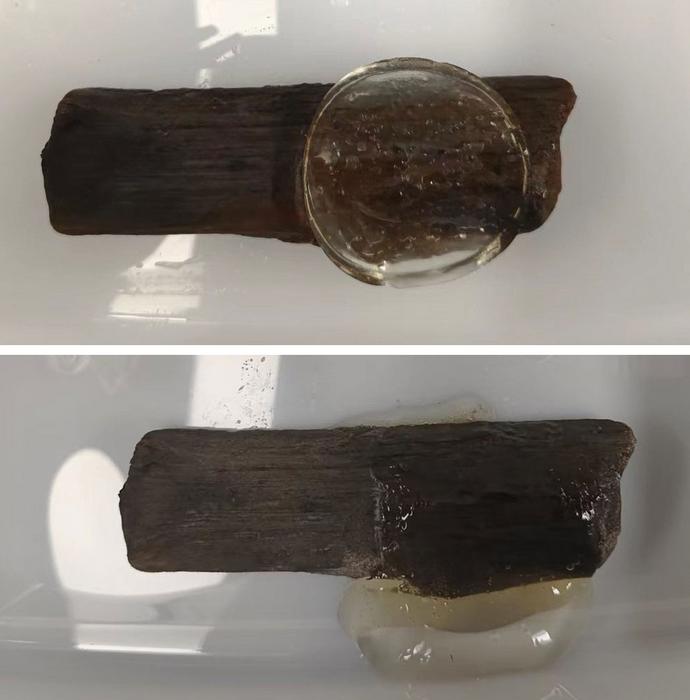

While newly-created gel could act like a face mask for the wood, the group noted, removing the substance could still harm its surface. In response to this issue, the authors of the study made a gel that would both provide the wood with compounds to fight bacteria and acid and gradually dissolve.

To do it, they mixed two polymers with the acid-neutralizing potassium bicarbonate, alongside silver nitrate: a compound historically used in photography to process prints. To create hydrogels with different staying power, they adjusted the amount of silver nitrate used. Those with more of the compound remained a “gooey solid.”

To test those hydrogels, they used 800-year-old pieces of wood from the Nanhai No. 1 shipwreck, discovered off of China’s south coast. The ship’s remains were discovered just over 80 feet below the sea in 1987. It is believed that the vessel was built between 1127 and 1279, during the Southern Song Dynasty.

The Nanhai No. 1 was recovered in 2007 and preserved at an aquarium in the Guangdong Maritime Silk Road Museum, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

“They found that each gel neutralized acid up to a centimeter deep after 10 days, but the dissolving gels that contained less silver did so more quickly, after one day. The team also found that artifacts treated with the liquifying gels better maintained their cellular structure and were less brittle than those treated with the solid gels,” the society said.

The study’s authors say their new hydrogel could enhance the world’s ability to untangle its mysteries. There are an estimated 3 million shipwrecks littered across the ocean floor, according to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.