Scientists called for humane ways to handle crabs, lobsters, and other shellfish in the kitchen after showing for the first time that crustaceans indeed feel pain.

Boiling lobsters and crabs alive has been a common method of killing them in the kitchen for many years with loud calls to end the cruel practice.

Shellfish are also currently not covered by animal welfare legislation in the EU, but this too could change.

It was suggested earlier that lobsters’ responses when treated this way were just reflexes, and that they were incapable of feeling pain, but new research suggests otherwise.

Researchers from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden have now detected pain stimuli sent to the brain of shore crabs, providing more evidence for pain in crustaceans.

“We need to find less painful ways to kill shellfish if we are to continue eating them. Because now we have scientific evidence that they both experience and react to pain,” study co-author Lynne Sneddon said.

Previous research has hinted at the likelihood of crustaceans feeling pain when subjected to mechanical impact, electric shocks or noxious acids touching their soft tissues such as the antennae.

In these earlier experiments, the shellfish reacted by touching the exposed area or trying to avoid the danger, leading researchers to assume that they felt pain.

However, information on the presence of specialised pain receptors in their body that detect such stimuli has remained elusive – until now.

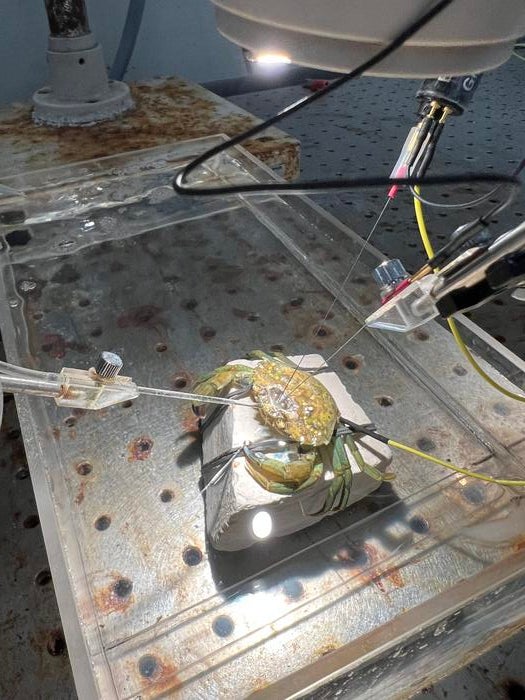

In the latest study, published in the journal Biology, scientists used EEG-style measurements to assess the activity in the brain of a shore crab.

They measured the activity in the brain’s central nervous system when the soft tissues of claws, antennae and legs were subjected to some form of stress.

Researchers showed clear nerve-cell reactions in the crustacean’s brain during such mechanical or chemical stimuli.

“We could see that the crab has some kind of pain receptors in its soft tissues, because we recorded an increase in brain activity when we applied a potentially painful chemical, a form of vinegar, to the crab’s soft tissues,” PhD candidate Eleftherios Kasiouras, who was part of the study, said.

“The same happened when we applied external pressure to several of the crab’s body parts,” he said.

The findings, according to scientists, indicate that shore crabs have some form of pain signalling to the brain from these body parts.

They also found that the pain response was shorter and more powerful in the case of physical stress than in the case of chemical stress, which lasted longer.

“It is a given that all animals need some kind of pain system to cope by avoiding danger. I don’t think we need to test all species of crustaceans, as they have a similar structure and therefore similar nervous systems,” the PhD candidate said.