Milton is the worst sort of poison,” declared the poet Ezra Pound in 1912. If you are not immediately sure who Milton is, or even what Pound means, then you are not alone: even Jenny Marx, wife of Karl, joked to her husband several decades previously, in 1875, that more Englishmen ate pork pies than read Paradise Lost, the shattering epic poem written by John Milton in 1667.

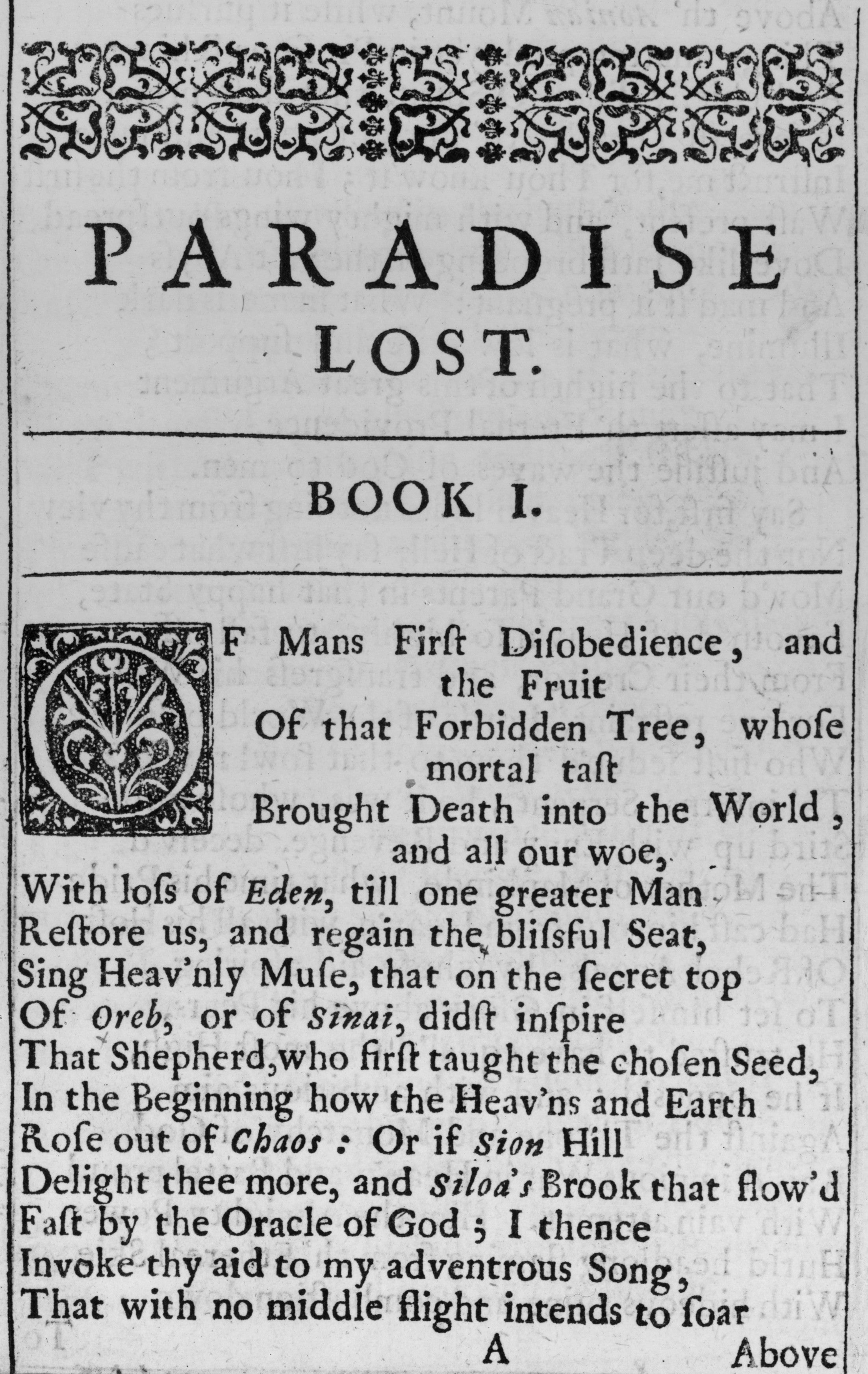

This magnificent opus, which tells the story of creation and of Satan’s dastardly revenge plan to destroy it, used to be recited by schoolchildren; now, one tends only to become acquainted with it during the course of an English literature degree. How far this canonical piece, which has at its centre the Christian foundational tale of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace, has itself fallen. Yet if any work of Western literature can claim to have exerted the greatest influence, aside from the Bible, on successive generations of politicians, philosophers, writers and radicals, Paradise Lost is that work.

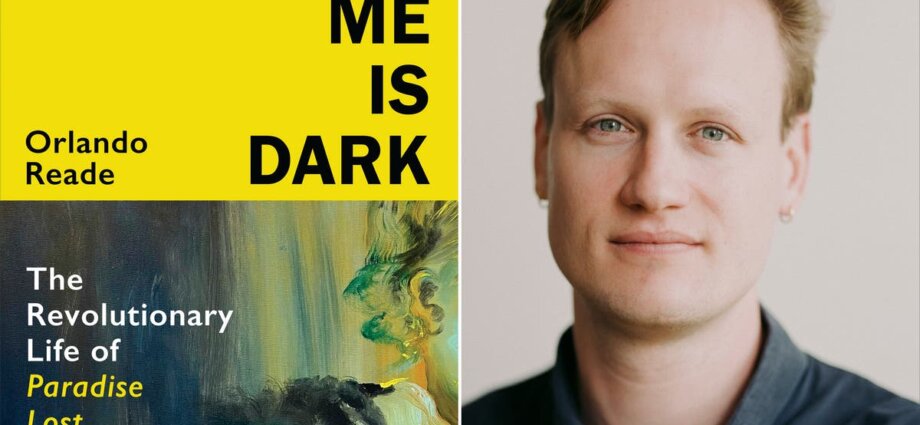

The history of Paradise Lost’s readership through the centuries, argues the academic Orlando Reade in an admirably lucid new book, What in Me Is Dark, is one of revolution, subversion, emancipation, and frequently disruptive interpretation. Some have regarded Satan and his diabolical emissaries as exemplars of white imperialism. Others have found in Satan, as he wages war against an omnipotent Christian God, the ultimate freedom fighter.

Yet more have seen, in his eventual incarnation as a tyrant, a sort of Julius Caesar-style warning against the false hopes of revolution. The poem’s iconoclastic wrestling with ideas of divine authority takes on new shapes depending on the reader: Thomas Jefferson read Paradise Lost as a hymn to individual freedom; Jordan Peterson sees in it an allegory of America’s wars – although Reade views this particular response with amusing scepticism. In 2013, at the height of the Arab spring, Kuwait banned the book altogether.

To understand the subversive, almost infinitely capacious history of this knottily intimidating biblical poem, dictated by a 63-year-old blind man over the course of several months and regarded ever since as a totemic cornerstone of establishment literary, one needs to go back to the beginning. Milton may personify the pale, male and stale hegemony of the English poetic tradition, but the story of his poem is one of new ways of thinking, of new societies being forged, of old orders being overturned – and it begins at the moment of England’s own revolution, with the overthrow of Charles I in 1649.

For 11 years England was a republic, yet the country was also violently divided between the royalists and those who believed the monarchy had become synonymous with tyranny. Milton was firmly on the latter side; he was also a startling progressive, who, in his job working for the Council of State, permitted the first translation of the Quran and petitioned for the right of women to divorce their husbands (his own first wife Mary had abandoned him, although they were later reunited).

Paradise Lost, argues Reade, is written in the volatile light of these radical struggles. And while it presents its central question concerning the nature of free will as a theological one, Reade points out that its most enduring legacy has always been political.

The devil has all the best tunes in Paradise Lost, and throughout history, the oppressed have often regarded Satan as a seductive avatar of their own struggles. (Malcolm X, who came across the work in a prison cell in Massachusetts in 1948 and immediately appropriated it into his activist thinking, took the opposite position: he read the poem as an endorsement of the Nation of Islam origin myth, which purports that Earth’s earliest inhabitants, some 76 trillion years ago, were Black.)

Yet Milton also imbued his masterpiece with a stranger, wilder, “dark” majesty that spoke not just to political movements but to individuals, particularly fellow writers. The Romantic poets saw in Milton’s febrile epic prose an intimation of the same wordless sublime they themselves restlessly sought.

Wordsworth in particular, who read Paradise Lost with his sister, Dorothy, argued that poets needed to throw off the “artificial, abstract concerns” of 18th-century poetry and recapture something deeper and more essential within the human spirit. (An initially passionate supporter of the French Revolution, Wordsworth became increasingly disillusioned with the revolutionary cause and found in Satan, as he mutates from agitator to dictator, a poetic simulacrum of Napoleon.)

A century or so later, Pound and TS Eliot were also reckoning with Milton’s legacy, but from an opposing perspective, regarding Milton as both outmoded and hopelessly antithetical to the modern sensibility. And nearly a century on from that, Reade finds himself teaching Paradise Lost as part of a literature class in a state prison in Newark. He concludes his book, in what is surely one of the greatest affirmations of Milton’s legacy, by noting that his students insisted on seeing the poem not as a work of literature but as “something that might help to explain why we had ended up where we were”.

Milton may have shaped his poem’s rebellious ideas about freedom around the unquestioned primacy of a Christian God, but as Reade points out, Paradise Lost today speaks to an era in which one “has the capacity to define the meaning of freedom for oneself”.

Poets, Shelley famously declared, “are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”. As that world wakes up to a moment in which the political order has been turned, yet again, entirely on its head, this neglected, restless, shapeshifting masterwork may well prove itself, once more, to be a poem for our times.

‘What in Me Is Dark’ by Orlando Reade (Jonathan Cape, £22) is published on 14 November