It doesn’t take long into our conversation before Jon Ronson and I are discussing whether Donald Trump is a psychopath. The author and journalist is the right man to ask, after all, given his 2011 bestseller The Psychopath Test was a global sensation that remains a ubiquitous presence on bookshelves to this day. “My answer to this,” says Ronson, chatting over Zoom from his home in upstate New York, “is when you look at Trump, what’s going on under the surface? Are there a lot of emotions? A lot of wounds that won’t heal? If that’s the case, he’s probably a narcissist. If what’s going on under the surface is nothing, then that kind of makes him a psychopath. The outward manifestation of psychopathy and narcissism is quite similar but it feels like there’s a volcano of emotions going on underneath Trump’s surface.”

For the book, Ronson – who’s also written about cancel in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, and terrorists and racists in Them: Adventures with Extremists – immersed himself in the world of psychopathy. He visited the most dangerous units of Broadmoor Hospital to interview patients, and found himself in the gauche Florida mansion of a once prominent CEO, as he explored the idea of how the cutthroat corporate world rewarded psychopathic behaviours, such as lying and deceit, lack of empathy, lack of remorse or guilt, egocentricity and a grandiose sense of self-worth.

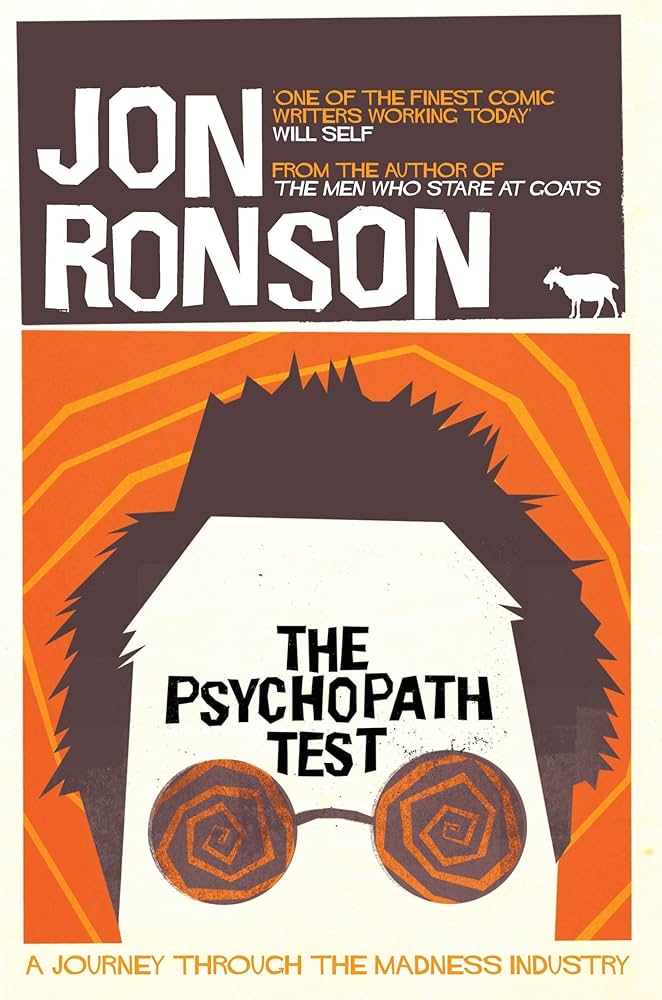

Ronson’s 2011 study went on “a journey through the madness industry”, using psychologist Robert D Hare’s famous checklist to identify psychopaths. Now, it’s a subject he’s returning to again for a UK-wide tour, as he asks “Do psychopaths rule the world?” while reopening the case “with exclusive anecdotes and fresh reflections, taking you on a thrilling exploration of madness and the elusive psychopathic mind”.

So, 13 years on from publication, what’s the enduring fascination for him? “It’s just so interesting,” he says, in his distinct, softly spoken voice, with those trademark round spectacles meeting my gaze. “For instance, this idea that of all the mental disorders, the one that we’ve decided to promote as a society is the very worst one. If you were going to choose a mental disorder to make society go around, to make the world turn, you wouldn’t want to choose psychopathy but yet we reward psychopathic traits. That’s fascinating.”

Ronson will also be exploring the huge spike in self-diagnosis in mental health. “It used to be that we would diagnose each other with disorders as a way of stigmatising that person, but that feels like it’s really changed,” he says. “There’s a huge amount of self-diagnoses going on, of things like trauma, ADHD and autism, which I want to talk about. When is that a good thing? When is that a bad thing? When does an expansion of mental health diagnoses benefit society? And when does it cause problems? Which I find interesting because I don’t have a strong ideological position on this. Sometimes it’s a really good thing, sometimes it’s bad.”

One of the other huge changes to have taken place, culturally and societally, since the publication of Ronson’s original book, is the insatiable appetite for true crime stories that has taken hold. Is there a danger this kind of subject matter can feed into the more unpleasant end of this? “I’m just so aware of that stuff that I’m not worried,” he says. “I feel very confident that I get it tonally right. But I agree with you. Some of these true crime podcasts are just so gleeful. They love all the blood and the gore. This [psychopath tour] isn’t like that at all.”

However, it does make Ronson pause for a moment to reflect on his own contributions to this. He seems a little uneasy thinking about his 2019 podcast series, The Last Days of August, which covered the suicide of the adult industry worker August Ames. “In many ways, it was a critique of true crime podcasting,” he says. “But, you know, maybe that slid a little too close to comfort for my ethical likings. August only died a couple of months before I started making that show and there I was poking around in people’s lives so soon after she died. So even though that show was really careful not to fall into those true crime podcasting traps, it’s still possible to do it.”

Ronson can draw a connecting line between our grisly obsession with true crime, and amateur sleuths, with the way people operate online. “It’s kind of like Twitter, in that we’re taking fragments of bits of information about somebody and then drawing an entire narrative about that person,” he says. “Which is very wrong. It’s a very bad thing to do.” Is there a direct correlation between the way people behave on social media and in real life, does Ronson feel? “I wouldn’t say social media promotes a lack of empathy but it certainly promotes a highly selective empathy,” he says. “And also, things like pathological lying. I think that’s another big change to society. Just think of the millions of public figures now who are accused of transgressions and they’re just unapologetic. Aspects of psychopathic behaviour are becoming more and more acceptable in our society, not just among our leaders, but among the general public too.”

With people leaving Twitter/X in droves and with less of a centralised platform to gather on, Ronson is beginning to feel like some of social media’s clout and influence may be on the downturn. “I think it’s losing power in a lot of ways,” he says. “I mean, X is just a mess. If you click the ‘for you’ tab instead of the ‘following’ tab, it’s just snuff videos. Videos of white people beating up Black people, and the caption is, ‘He f***ed around and found out.’ Death videos. Videos of people getting hit and killed by cars. I mean, Jesus Christ. That’s X now. I never thought I’d say this, because of all the good that Twitter used to do, but I’ll actually be relieved if X collapses at this point.”

Twitter/X has become, for Ronson, a place with no redeeming features left. “Those positive things don’t really seem to happen anymore,” he says. “It’s just videos of people being maimed or killed, and lies. The one positive thing that’s come from it is that it’s defanged the worst side of left-wing publishing, where you might have a main character figure with hundreds of thousands of followers who can instigate a pile-on. That doesn’t really exist anymore because everybody’s fled. Those people have moved to [invite-only X alternative] Bluesky and that doesn’t have the power. But what’s taken its place is this gross right-wing public shaming. All the years they were going on about how terrible cancel is and the minute they had the power, they did the same.”

He compares the exodus to a scene that his friend, the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis, predicted. “At the beginning of Twitter, Adam said to me that it’s going to create an internet that’s going to be like a John Carpenter movie,” he says. “All of these warrior gangs yelling at each other and then, just like in those John Carpenter movies, most people are going to want to leave to the safe suburbs where people are nice to each other. He said that to me in about 2009 and it sort of feels that that’s where we are now.”

While I may have been expecting a somewhat diplomatic response from such a seasoned journalist as Ronson, when I ask him his views on the man behind Twitter/X, he simply cannot hide his disdain for Elon Musk. “He just epitomises despicability,” he says. “Just the other day, he’s standing next to Trump and he says if Kamala wins the next election this will be the last election and that he’s genuinely worried there’ll never be another one. I’m just like, f*** off with that scaremongering bulls***.” And don’t get him started on another area of Musk’s cultural impact. “Have you seen those cyber trucks?!” he exclaims, animated and angry. “Have you seen what they look like in the flesh? God, it’s like a civil war. It’s all totally signalling like a sort of f***-you swagger.”

So, Musk is not someone Ronson would be interested in as a subject to sit down with? “I’m going to make a third season of Things Fell Apart,” he says of his-wars podcast. “And I’ve been thinking about Elon Musk as somebody who I could explore for that. But I’m not entirely sure. Maybe we all know what we think about him and that’s enough. I listened to a couple of biographies on him and I want to try to surprise people but I didn’t find anything about Musk that we don’t already know.”

As someone who has spent a prolonged period of time submerged neck-deep in a world of conspiracy theories, wars, and generally some of the more perturbing, nefarious and baffling aspects of the modern world that we occupy, rather than feeling burned out or despondent, Ronson appears to be clinging onto hope. “In terms of America, I feel, in the long run, a bit more optimistic,” he says. He thinks the provocative right-wing mega troll types, who over the years have emerged and run rampant from the darkest depths of the internet, may be waning. “I’m not sure how sustainable it is, honestly,” he says. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it goes out of vogue because I think people are getting sick of division wherever it’s emanating from.”

He also feels we may be about to see a generational attitudinal shift come into play. As someone who has witnessed his son’s formative teenage years at the same time he’s documented the wars, Ronson has seen this up close. “Younger kids are coming up now and I don’t think they are as involved in these things as their older siblings,” he says. “I remember thinking when So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (2015) came out that the young were creating a set of rules for themselves that were so stringent and draconian that they wouldn’t be able to abide by them themselves. I think younger kids are coming along and seeing these rules that their older siblings created, and they’re like, f*** that, I’m not spending my life tiptoeing around a minefield.”

He’s even veering towards a positive outcome for the upcoming election. “If I had to put money on it, I’d say that Kamala is probably going to win,” he says. “I could absolutely be wrong about that, but I just can’t bear the thought of another four years of Trump.”

Jon Ronson’s Psychopath Night is touring across the UK from 12 October. Tickets here.