Archaeologists are revealing the long-lost secrets of the real First World War – a series of conflicts that unfolded across much of Europe, the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East some 32 centuries ago.

New research published on Monday reveals how two substantial armies from two different parts of Europe fought to the death in a major battle just south of the Baltic Sea. The two armies appear to have come from at least 400 miles apart – a southern one from Bavaria (or from what is now the Czech Republic) and a northern one from what is now north-east Germany.

But the battle, involving up to 2,000 warriors, seems to have been part of a series of conflicts and crises which caused chaos across a large swathe of the world from Scandinavia to the Sahara and from Western Europe to what is now Iraq.

The battle, just south of the Baltic, was fought in the valley of the River Tollense in around 1250BC.

“It appears to have been just the tip of a conflict iceberg which spread turmoil across vast areas in the mid-to-late 13th and early-to-mid 12th centuries BC,” said one of the world’s leading authority on the period, Professor Barry Molloy of University College Dublin.

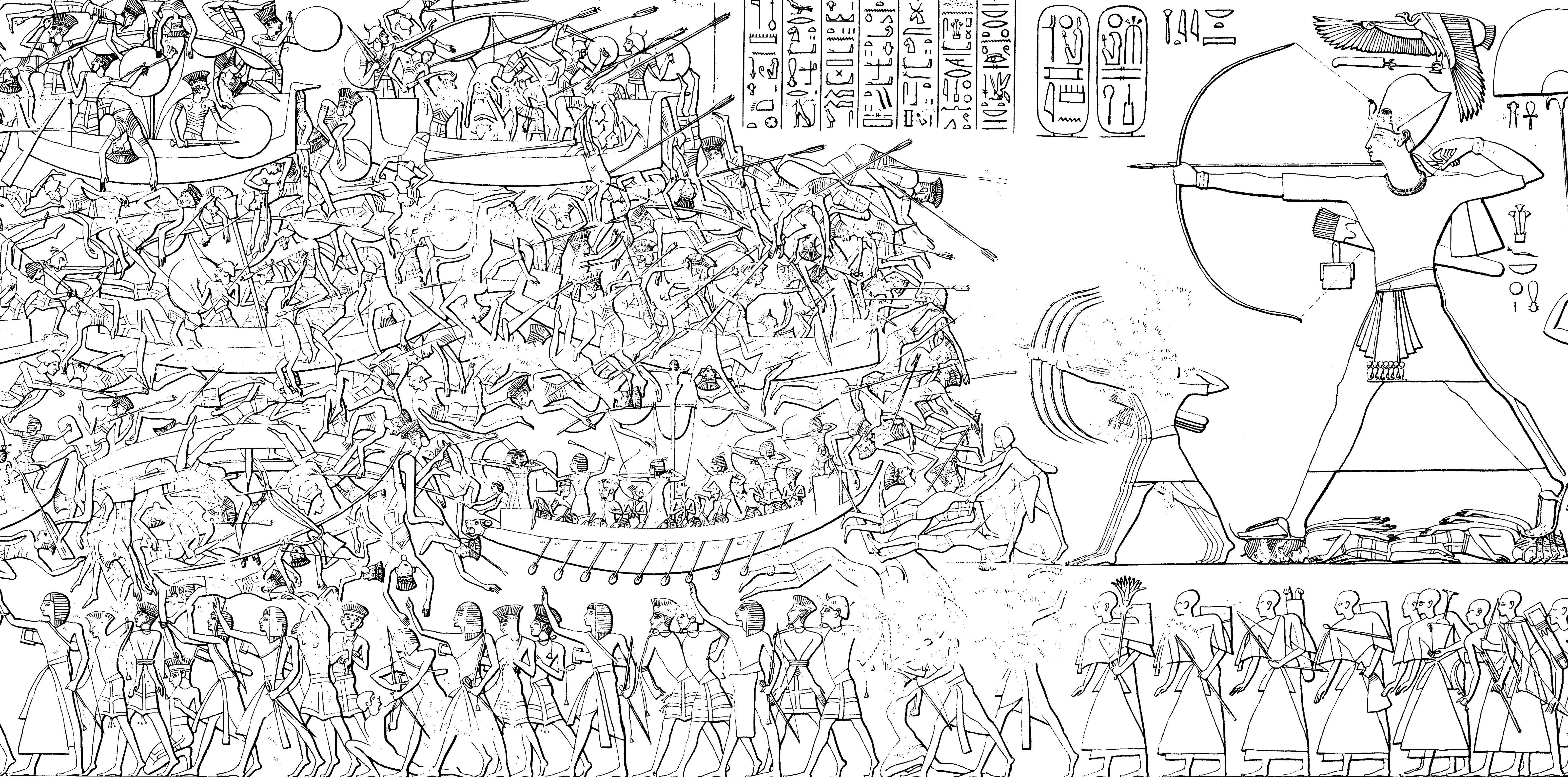

It was a time of huge political and economic instability, which saw the fall of the first great Greek civilisation (the Mycenaeans) from around 1230BC, the collapse of the Middle East’s Hittite empire in the 1190s BC, the weakening of ancient Egypt from around 1180BC, and the decline of Babylon by 1155BC.

It also seems to have seen the final 13th century BC collapse of the Indus valley civilisation, the 12th century decline of major political centres in Romania, Hungary and northern Serbia and the construction, in the 13th century BC, of defensive ramparts (ie, probable evidence of conflict) in Bavaria, Austria, Bohemia, and as far west as Ireland.

At roughly the same time there was even major economic and social disruption in North East China and a very pronounced rise in the portrayal of military violence in Scandinavia.

Crucial new research, on the collapse of the Hittite empire, was published by American scientists only last year – and key new evidence has been discovered by French and other archaeologists over recent years, revealing how the Late Bronze Age Collapse impacted Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean region.

The battle in north Germany in around 1250BC is not only the earliest known major battle in Europe – but was also much bigger than previously thought. So far, archaeologists have unearthed the remains of 160 warriors – but they have only excavated a tiny fraction of the battlefield, so it’s likely that the bones of many more Bronze Age warriors will be discovered.

They have so far also found 54 bronze arrowheads – but it’s believed that most arrows and other weapons were retrieved by the victors so that they could be reused.

An examination of the warriors’ injuries has revealed that arrows were probably the main cause of death – but wooden clubs, spears and bronze swords were also deployed with lethal effect.

But it’s a detailed study of the bronze arrowheads which has yielded the most remarkable revelation – namely that they were of two totally different designs: one from north-east Germany, the other from southern Germany or from Bohemia or Moravia in what is now the Czech Republic.

That’s the key information that suggests that the two armies came from very different parts of central Europe, at least 400 miles apart. The crucial new evidence is being published today by the prestigious UK-based academic journal, Antiquity.

The archaeologist who carried out the research on the arrowheads, Leif Inselmann at Göttingen University in Germany, says that the findings “suggest that European Bronze Age fighting forces were far more mobile than previously thought”.

Part of the battle was fought around a strategically and economically important bridge across the Tollense river. Indeed it may well have been a conflict over control of a vital trade route. That’s because the well-constructed Bronze Age road over the bridge was part of an important long-distance route connecting southern Europe with the Baltic (and it’s known that trade between the Mediterranean and Scandinavia involved valuable commodities like Mediterranean glass beads and copper and Baltic amber).

“Our study of this battlefield completely changes our understanding of Bronze Age society,” said the prehistorian, Professor Thomas Terberger of the University of Göttingen, a co-author of today’s Antiquity paper.

“Our investigations have been revealing the unexpected scale and level of military and political organisation in that period,” he added.

“The battle in the Tollense Valley is the earliest direct archaeological evidence ever found for fighting between substantial armies in Europe,” said University College Dublin’s Professor Molloy.

Interestingly, the battle in the Tollense Valley (and many of the other Late Bronze Age instability events elsewhere in Europe and the Middle East) took place at around the same time as iconic stories described in the Bible and in Greek epic literature – including the Israelite Exodus from Egypt and the Trojan War.

Taken as a whole, the instability, economic decline and widespread violence of the mid-to-late 13th and early-to-mid 12th centuries BC is known as the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

It is increasingly being seen as not only a very major transformative episode in world history, but also one of its most complex and enigmatic. Although substantial amounts of research are currently underway, it’s not yet known what caused the collapse.

Climatic factors were almost certainly involved, but earthquakes and disease pandemics are likely to have also played their part.

What’s more, another factor was almost certainly involved – a factor which has profound implications for our own 21st century AD world, threatened as it is by climate change and other phenomena.

The pre-collapse Bronze Age civilizations were, in many ways, extremely complex, especially in organisational, political and economic terms – and they therefore appear to have exceeded their ability to “reassemble” themselves after a major environmental, economic or military shock. It’s a phenomenon which historians call “overshoot”.

What’s more, it’s not yet fully understood how the different conflicts in different parts of the Bronze Age European, Middle Eastern and North African worlds were or were not connected. However, because of societal and economic complexity, especially trade links and technological interdependence, it is likely that, like falling dominoes, many of the conflicts and crises of the Late Bronze Age Collapse triggered other conflicts and crises in other areas that had not yet been affected.

At the battle site currently being studied in northern Germany’s Tollense Valley, it’s also not yet clear who won that particular battle, although some evidence points towards an at least temporary victory for the local north German population.