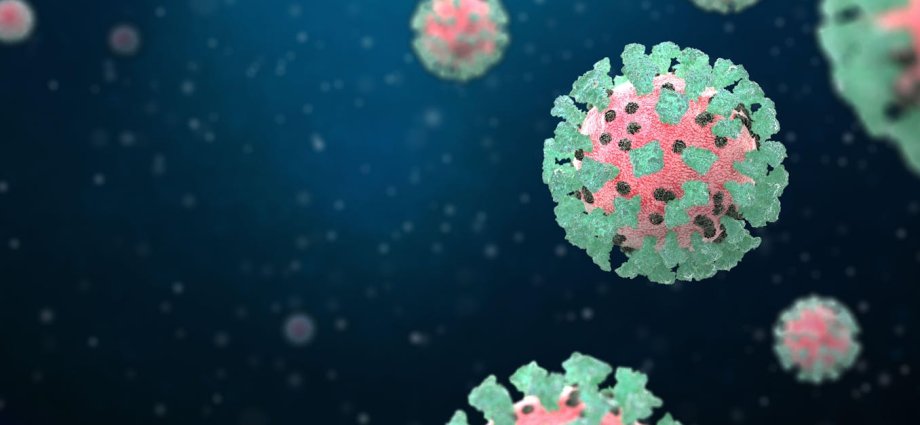

A new COVID variant is spreading rapidly and could soon become the dominant variant around the globe. The variant, called XEC, was first detected in Germany in August and appears to have a growth advantage over other circulating variants – but it is not a radically different variant.

XEC is what’s known as a “recombinant variant”. Recombinants can occur naturally when a person is simultaneously infected with two different COVID variants.

XEC is the product of a recombination (exchanged pieces of genetic material between two variants) between the KS.1.1 variant and the KP.3.3 variant. These two parent variants are closely related, having both evolved from JN.1, which was the dominant variant around the world at the start of 2024.

XEC was first reported in early August 2024 in Germany and a few other European countries but has since continued to spread, with over 600 cases identified in 27 countries across Europe, North America and Asia.

Scientists identify XEC cases using a public database called Gisaid, to which genetic sequences of viruses are uploaded for analysis. It is here that mutations in SARS-CoV-2 are spotted (SARS-CoV-2 being the virus that causes COVID).

But it’s a bit like a drunk looking for his lost keys under the street lamp because that’s where the light is best. In other words, more cases of new variants are spotted in those countries that typically sequence more COVID samples through routine surveillance programmes.

Countries with the highest number of identified XEC cases as of September 18 are the US (118), Germany (92), UK (82), Canada (77) and Denmark (61). Of course, these numbers could be higher in countries that don’t routinely sequence COVID samples.

Currently, the dominant variant in Europe and North America is KP.3.1.1, while the closely related KP.3.3 dominates in Asia.

XEC is a minority variant and its prevalence is highest in Germany, where around 13% of sequences are potentially XEC. In the UK, prevalence is around 7%, while in the US it is below 5%. However, XEC appears to have a growth advantage and is spreading faster than other circulating variants, suggesting it will become the dominant variant globally in the next few months.

XEC has very similar genetic material to both its parent variants as well other circulating variants, which are mostly derived from JN.1.

One reason for XEC’s advantage could be the relatively rare T22N mutation (inherited from KS.1.1) combined with Q493E (from KP.3.3) in the spike protein. The spike protein is a critical part of the virus that binds to human cells, enabling the virus to gain entry and start replicating. However, little is known about the effects of the T22N mutation on how well the virus can replicate or spread between people.

But does it cause worse disease?

We don’t have data yet from patients or laboratory experiments to tell us what kind of illness XEC is likely to cause – although this data is expected soon. However, this new variant will probably be similar to other COVID variants in terms of the disease caused, given its similar genetic information. So symptoms such as a high temperature, sore throat with a cough, headaches and body aches along with tiredness are to be expected.

Hospitalisations usually increase in winter as a consequence of colder temperatures and increased spreading of viruses (due to people being indoors more). So these increases, when they come should not necessarily be associated with the new variant.

The campaign for autumn booster in the UK will start in October with an updated vaccine targeting the JN.1 variant, which XEC derives from, assuring a good level of protection against severe illness.

XEC is the latest in a long list of past and current COVID variants being monitored as the virus naturally evolves. Recombinant variants themselves are nothing new, as COVID cases in 2023 were dominated by the XBB recombinant variant.

Several other closely related variants are being monitored, such as the MV.1 variant, which like XEC also has the T22N mutation in the spike protein. MV.1 was originally reported in India in late June and has also spread rapidly to other countries, making it one to monitor in the future.

XEC may well become the dominant global variant, but it could be outcompeted before then or replaced quickly afterwards by a different but closely related variant.

Richard Orton receives funding from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust

Wilhelm Furnon receives funding from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust.