Simon Camponuri was conducting fieldwork in Central California’s Carrizo Plain National Monument around 2016, studying Giant Kangaroo rats and other endangered species with researchers from UC Berkeley.

The team had hoped to examine the impacts of climate change on wildlife in the desert landscape after California’s 2012 to 2016 drought – one of the most severe in state history.

But as the group trod around rodent burrows, they kicked up dust, unknowingly exposing themselves to Valley Fever. Three researchers ended up contracting the dangerous lung infection.

“That really made it clear that there was a part of the ecosystem that we weren’t really paying attention to,” Camponuri told The Independent last week.

Camponuri, now a PhD candidate at Berkeley, UC San Diego associate professor Alexandra Heaney, and scientists at institutions across the country have since found that the spread of Valley Fever in California has links to climate change, and more people are appearing to be infected each year. Their findings were recently published in the October issue of The Lancet Regional Health Americas.

Valley Fever, officially called coccidioidomycosis, was first discovered in Southern California’s San Joaquin Valley. The lung infection is caused by a fungus that grows in soil in western parts of the US, with the majority of cases reported in California and Arizona.

While Camponuri’s colleagues recovered, as many as 10 percent of those infected will develop serious or long-term problems in their lungs. Another 1 percent will see it spread to their skin, bones, joints, or brain. Valley Fever that progresses to infect the brain is fatal if not treated.

Valley Fever is caused by breathing in infectious spores, although some who are exposed are never infected. The spores can be kicked up during wind events, or through agricultural work and construction. The symptoms include fatigue, cough, fever, headache, shortness of breath, night sweats, muscle aches, joint pain, and a blotchy red rash on the upper body or legs.

Those over 60 are more likely to be infected, as well as those who have weakened immune systems, are pregnant, have diabetes, and people who are Black or Filipino.

There are between 10,000 and 20,000 cases every year in the US but it’s possible that thousands more are misdiagnosed or never reported.

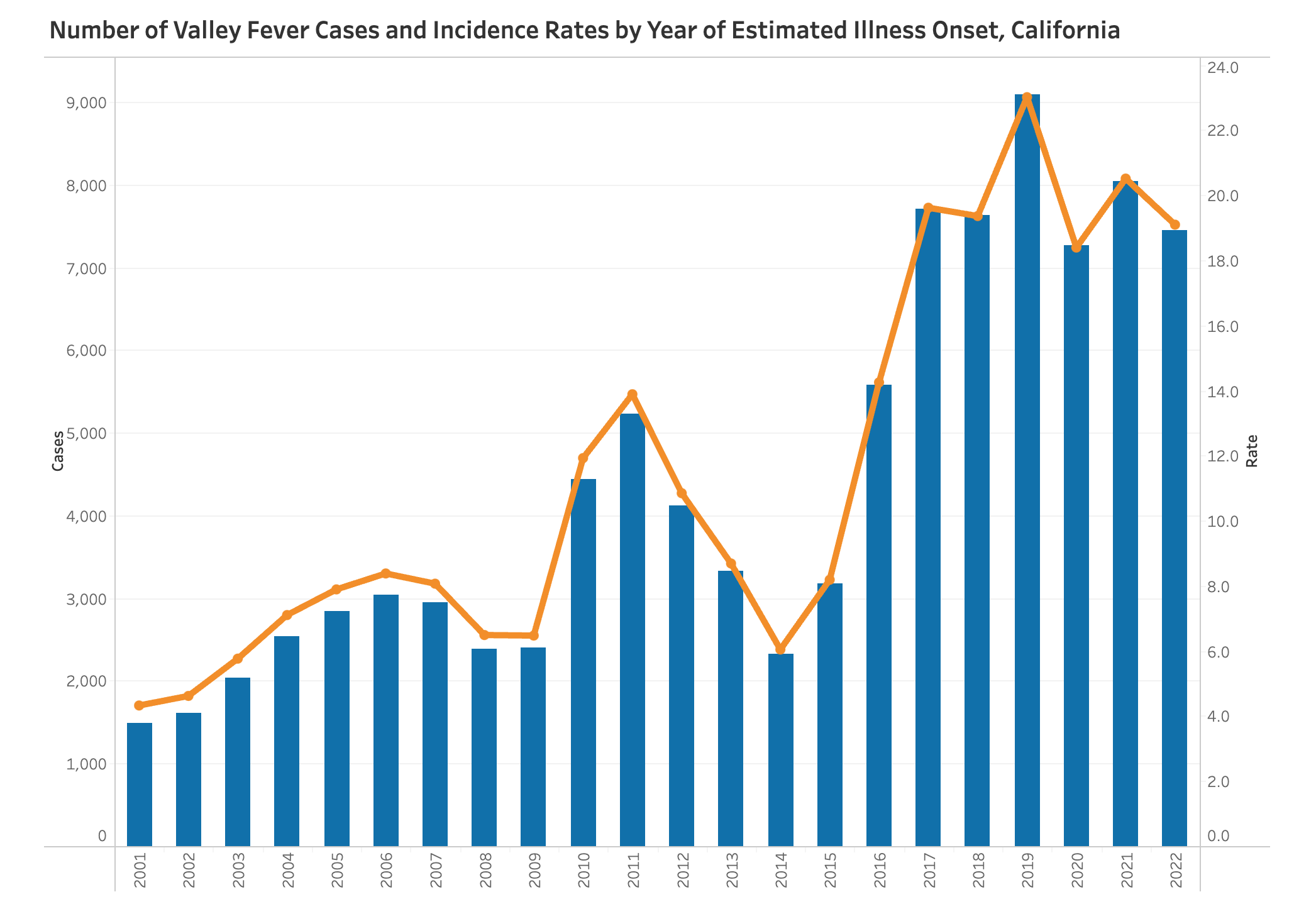

In the past decade, cases have surged in California. Between 2014 and 2018, the number roughly tripled from around 2,300 to more than 7,600. Last year, more than 9,000 cases were reported in the state, and by July of this year there were already 5,000 cases.

The reason for such a massive increase has been elusive.

But now, after years of research, Camponuri and his colleagues found that cases of the disease spike in California during a shift from drought to heavy rain and flooding.

The West has seen increasingly extreme and erratic weather patterns, linked to the climate crisis. The region is the grips of a megadrought, the driest period in at least 1,200 years. On the flip side, there are periods of extreme wetness, and the last two winters have seen atmospheric river storms deluge the state with record rainfall.

These swings from extreme dry to wet conditions have led to an explosion in Valley Fever cases. The San Joaquin Valley’s Kern County recorded 1,100 cases in 2015. The annual caseload has jumped to more than 3,000 since 2018.

This year, Valley Fever infected 19 people at the county’s outdoor “Lightning in a Bottle” music festival including eight hospitalizations. By the end of July, California has seen more than 6,200 suspected, probable, and confirmed cases, with 2,196 in Kern County alone.

Professor Heaney said that a wet winter provides ideal conditions for the growth of Valley Fever, then summer dries out the land, breaking the fungus down into infectious spores.

As the soil gets disrupted – by wind or feet or labor – the spores shoot into the air. While people can get Valley Fever at any time of the year, they are more likely to be infected during late summer and fall. Cases typically peak between September and November, due to a delay from infection to reporting.

For the two years after a 2012 to 2016 drought in the state, the scientists observed larger-than-average peaks.

Fungal spores are possibly good at “just persisting” in drought conditions as other microbial competitors die in harsh conditions, leaving them more room to grow. The wetter the winter, the bigger the fall peak could be, Heaney suggested.

At the end of August, California health authorities warned of another possible increase in cases.

“We saw almost a record number of cases last year,” said Heaney. “And, we are concerned that this year, in the fall, is going to continue to be a really big year for cases.”

The main way that people can protect themselves from infection is by understanding risk factors and how to stay safe.

“Mostly avoiding dust. We think that dust is the thing that is most associated with being at risk,” Camponuri said. “I think people who are most at risk are people who work outdoors.”

The Independent will be revealing its Climate100 List in September and hosting an event in New York, which can be attended online.