A newly discovered ancestor of the extinct Tasmanian tiger had “extremely thick” jawbones to pick clean their prey, including bones and teeth.

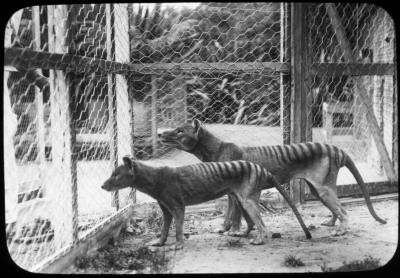

This is according to a new study published on Saturday in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. It describes three ancient species of the modern Thylacines, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger that went extinct 88 years ago.

The research was published on the ocassion of Australia’s National Threatened Species Day, which marks the death of the very last Tasmanian tiger on 7 September 1936.

Researchers said the newly discovered species were the “undoubted oldest members” of the Tasmanian tiger and roamed Australia 23-25 million years ago, during the late Oligocene.

Their fossils were unearthed in Riversleigh World Heritage Area.

The study sheds more light on the ecology of the region millions of years ago, changing previously held ideas.

“The once suggested idea that Australia was dominated by reptilian carnivores during these 25 million-year intervals is steadily being dismantled as the fossil record of marsupial carnivores, like these new thylacinids, increases with each new discovery,” study lead author Timothy Churchill said.

Scientists now believe the diversity of mammalian carnivores in the Riversleigh area during this period rivals that of any other ecosystem in the world.

The largest of the newly discovered species, Badjcinus timfaulkneri, weighed upto 11 kg, about the same as a large Tasmanian Devil.

It possessed an extremely thick jawbone which enabled it to crush even the bones and teeth of its prey. This species was related to the far smaller, previously discovered B turnbulli, which was the only other thylacinid known from this period.

Another species found in recent excavations is Nimbacinus peterbridgei, which was about the size of a Maltese Terrier, researchers said.

Scientists identified and labelled the species based on near-complete teeth fossils, and believe it was a predator that fed on small mammals and other diverse prey species living with it in the ancient forests.

Researchers suspect N peterbridgei could be the oldest direct ancestor of the Tasmanian tiger yet known.

The last of the three species identified in the new study is Ngamalacinus nigelmarveni, which was about the size of a Red fox, weighing close to 5.1 kg.

Molar fossils of this species suggest it was highly carnivorous, “more so than any of the other thylacinids of similar size”.

“These thylacinids exhibit very different dental adaptations, suggesting there were several unique carnivorous niches available during this period. All but one of these lineages, the one that led to the modern Thylacine, became extinct around 8 million years ago,” study co-author Michael Archer said.

“That lineage of these creatures that survived for more than 25 million years ended with the death of Benjamin, the last Tasmanian tiger in Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo on 7 September 1936.”