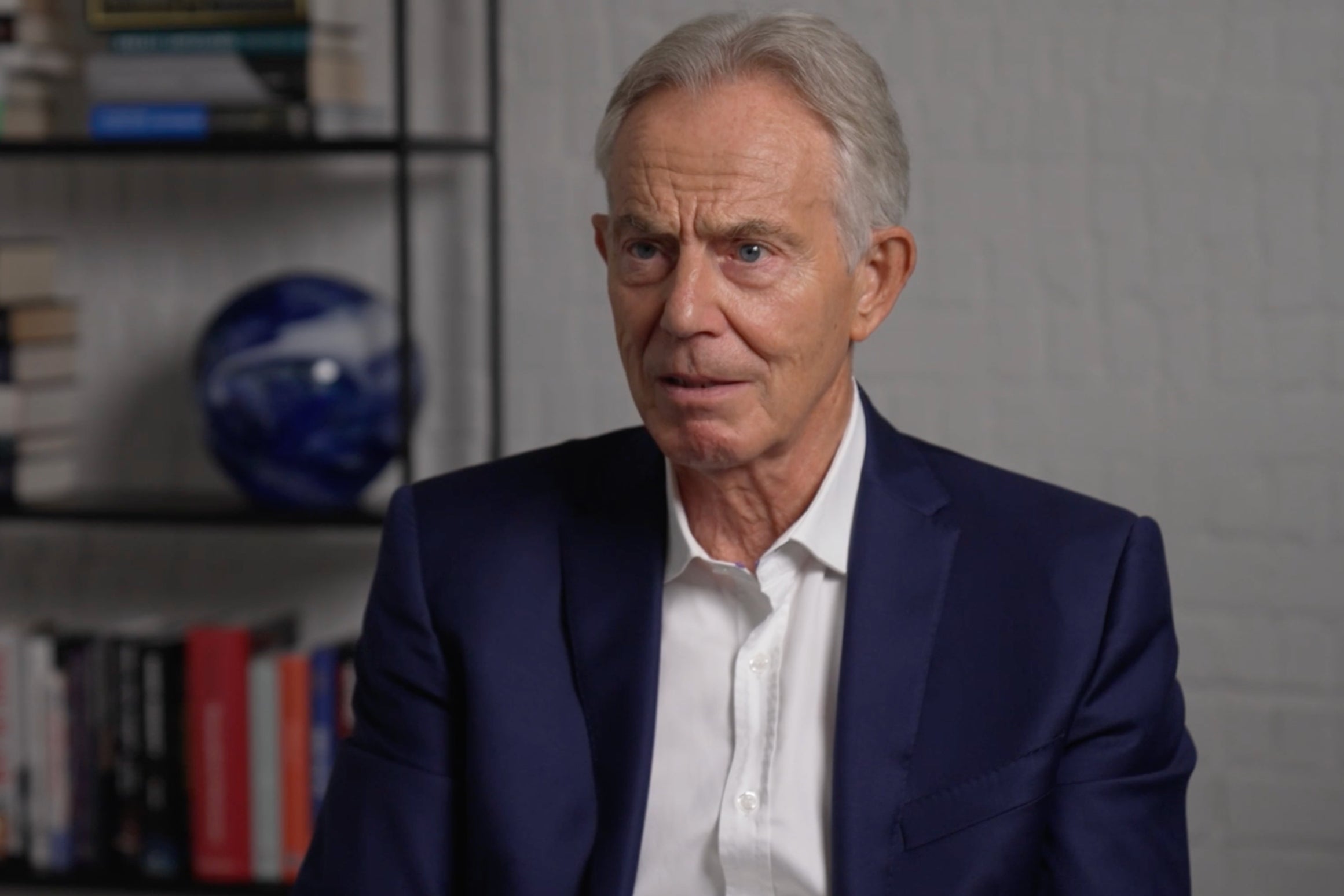

In a disarmingly personal interview, Sir Tony Blair discloses how his desire for political power was triggered by the early trauma of his father having a stroke and the death of his mother.

Speaking to Geordie Greig, editor-in-chief of The Independent, the former prime minister said his ambition to gain power came directly from those tragic moments. He was aged 10 when his father was incapacitated and 22 when his mother died.

Watch the Blair interview in full on Independent TV

The former Labour leader declares as his new book, On Leadership, is published: “The moment I saw what power was and what it could do, I wanted it.”

As well as providing a masterclass in how to wield power, it also reveals his personal faults and successes during his decade in No 10 as well as the next 17 years forming the Tony Blair Institute, which today has 1,000 staff and advises governments of more than 40 countries.

“Power should be based on a desire to do something that you believe as a matter of conviction and principle. But, if you are being honest the power itself is attractive. It doesn’t mean you should pursue it at the expense of the principle, but your wanting to exercise leadership in the exercise of power is what goes with it,” he explains.

His motive when he was young, he says, was always “to change the world, to put principles into practice, to be respected and recognised as a person with power and to feel that power, to feel how it could shape my world around me as well as the world of others”.

The impact of his mother dying aged 52 and his father’s devastating stroke at 40 was profound. “I realised the fragility of everything, our life circumstances changed completely, our main source of income had gone. It was three years before dad could even speak again. It haunted me ever after and made me what I am,” he says.

“I remember my mother coming in that morning. Dad had come back from an event, late at night and I could tell immediately something’s wrong in the way that you do as a child. Then she explained that he was in hospital and had been seriously ill.

“We thought he would probably die, but he didn’t. Nowadays, they treat strokes completely differently, much better. Forty is a young age to have a serious stroke. Dad was just about to stand for what was a pretty safe Conservative seat in the northeast of England. He was a barrister, so everything was about communication. Suddenly his entire life trajectory changed, and he had to learn to speak again, which is very difficult.”

Sir Tony recalls going to school and praying with a teacher that day, adding: “I never spent a lot of time psychoanalysing myself. But of course, when something like that happens, you realise if I’m going to make something of my life, I’d better get on with it and work hard.”

It is advice that he has imparted to his own children.

“I used to say to my children work hard, play hard and you’ve got a chance for success. But play hard, work hard then you are probably going to fail. Work hard first. Like most of what I told them they would ignore it completely! But I still think it’s true what I said,” he says.

Sir Tony’s close relationship with his children also came out in advice he later received from his son Euan about speaking at a conference on cryptocurrencies.

“When I asked him what to say, even after he had given me some notes he bluntly said, just tell them you’re sick, you’re not fit for prime time on this subject!”

Sir Tony wryly adds: “But I did address them, unfortunately.”

His struggles on that technical topic reflect his view that there are two different types of brains – artistic and scientific. Sir Tony puts himself in the first category, as an unfortunate rare failure at school proved.

“I’m on the art side. My physics teacher was in awe of how bad my physics paper was, and I failed miserably. I do try to read more about science to try and understand it but I know my own brain has difficulty understanding scientific concepts.” A big contrast to Margaret Thatcher who liked to boast that she was a scientist.

Learning while leading is a central theme of his new book, in which he recalls a “humiliating” early attempt to tackle antisocial behaviour and criminality, core to his premiership.

“There was a guy on the street peeing against the door of someone’s house, and this is late at night. I was coming back from the Tube and I sort of confronted him. He pulled out a knife. So I moved on. But you know, even such small crimes leave you with a lingering sense of anger and humiliation. I’ve always been very tough, hardline on crime. I think it’s really important – the first duty of government is to keep people safe.”

The constant for Sir Tony throughout his adult life has been his marriage to Cherie. He calls it “a joint leadership” within their family but admitted he may be getting into trouble with her after it is pointed out to him that he barely mentions women in his new book. “But more than half I employ are women”, he says in his defence. He also boasts of creating more female MPs than ever before as well as in the cabinet.

He counts himself lucky to have had “a devoted marriage”.

“What I never do is to preach to people about personal lives. I’m just lucky with what I have. And I think the most important thing in any relationship is that you respect the other person,” he says.

His Christian faith became an issue during his premiership not least when Jeremy Paxman asked if he prayed with George W Bush. His press secretary Alastair Campbell once interrupted an interviewer to say, “We don’t do God.” And the Bible plays a part in his new book – there are almost a dozen biblical references, but he says that they are there “accidentally” rather than deliberately.

He adds: “It’s also just an interesting concept of leadership as Moses leads people to the promised land. But actually, most of the time people are complaining: ‘Why did you bring us out of Egypt? We’d have been better to stay back there in slavery.’”

Every day, Sir Tony thinks of the empowerment his parents gave him, focused on what is required of the leadership and the strength and ambition they imbued. “It must be exercised in a way that fulfils a mission or purpose, otherwise you’re just occupying an office,” he says. ”You are then just a placeholder and not a leader. For me it was very simple: it was about the modernisation of Britain and to try to do good in the world. I don’t think you should ever go into politics unless they want to change things.”

Today, Sir Tony has democracies and dictators as clients. “It has to be about the leadership moving in the right direction. If they’re moving in the wrong direction I don’t want to be part of that,” he says. “They must make reforms that are going to make them more open, more successful. Then I will work with them even though it’s a system with which I might have disagreements.”

Of course, Sir Tony’s own time in government was unique in that his first and only job was as prime minister. “My book is about the things I wished I had known when I came in – it would have shortened the learning curve.”

There is a sparkle, clarity and charisma about Sir Tony, now aged 71, almost uniquely among politicians, which was why George Osborne, when chancellor, referred to him as “The Master”. But even as one of his final chapters is titled “How to Handle Criticism” and another “Protect Your Legacy”, he candidly insists all former leaders must actively do both. He shows a particular ruthlessness in dealing with carping critics. “Treat him like a psychopath you are unable to remove. Once you accept you can’t escape him, you deal with that, and find a way so that he shall not define you,” he says.

As Sir Tony metaphorically locks the attic door to keep the demons at bay, he hopes history will be kind to him. As to regrets, he says: “I always say that is for me to know and others to find out!”