Scientists have developed a groundbreaking technique to peer through organs by turning tissue transparent with a common food dye.

The new technique is detailed in a study published on Thursday in the journal Science.

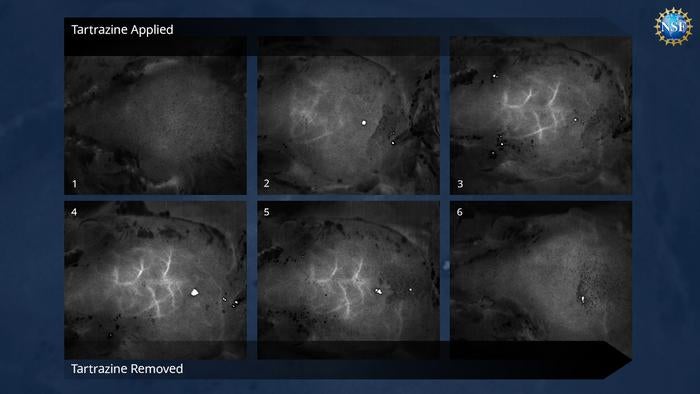

Researchers turned skin and muscle tissues of live mice transparent by applying a yellow food dye known as tartrazine, which is commonly used in snack chips and candy coating. They found the method was reversible and “undone with a quick wash”.

This technique could revolutionise medical diagnosis by helping locate injuries, monitor digestive disorders, and even identify cancers.

“Looking forward, this technology could make veins more visible for the drawing of blood, make laser tattoo removal more straightforward or assist in the early detection and treatment of cancers,” said Guosong Hong, one of the study’s authors from Stanford University.

“Certain therapies use lasers to eliminate cancerous and precancerous cells but are limited to areas near the skin’s surface. This technique may be able to improve that light penetration.”

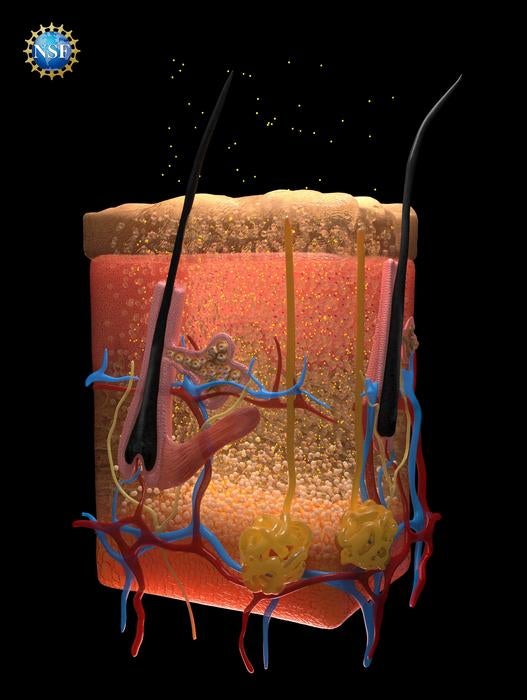

In the study, researchers assessed the physics of skin scattering and refracting light, which is the phenomenon of light changing speed and bending while travelling from one material to another.

They found that aqueous portions of skin tissue bent light less compared to its components made up of protein and fat.

Typically, then, turning skin transparent would require clearing away the proteins and the fats, which wouldn’t work on a live animal.

So researchers developed a new method to match the bending abilities of the various skin cell components so light could travel through unimpeded.

Dyes that absorb light effectively are known to direct light rays uniformly. When researchers dissolved tartrazine, commonly known as FD & C Yellow 5, in water and made tissues absorb the mixture, the dye molecules matched the light-bending abilities of various cell components, preventing light from scattering.

They first tested the dye solution on thin slices of chicken breast. As they increased the concentration of tartrazine, the meat slice became more transparent.

When they later applied the solution to mice scalp, it turned the skin transparent to reveal blood vessels crisscrossing the brain.

When they rubbed the dye mixture onto the rodent’s abdomen, the skin faded within minutes to reveal the contractions of the intestines and movements caused by breathing and the beating of the heart.

Scientists said the application of the dye solution could lead to deeper views, with implications for both biology and medicine.

“It’s important that the dye is safe for living organisms. In addition, it’s very inexpensive and efficient. We don’t need very much of it to work,” Zihao Ou, another author of the study, said.

Researchers have yet to test the dye on human skin, which is about 10 times thicker than that of a mouse.

“Many medical diagnosis platforms are very expensive and inaccessible to a broad audience but platforms based on our tech should not be,” Dr Ou said.