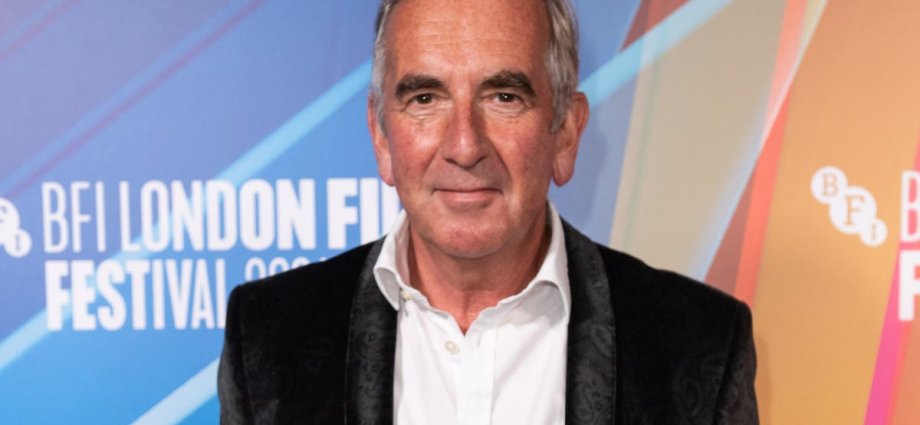

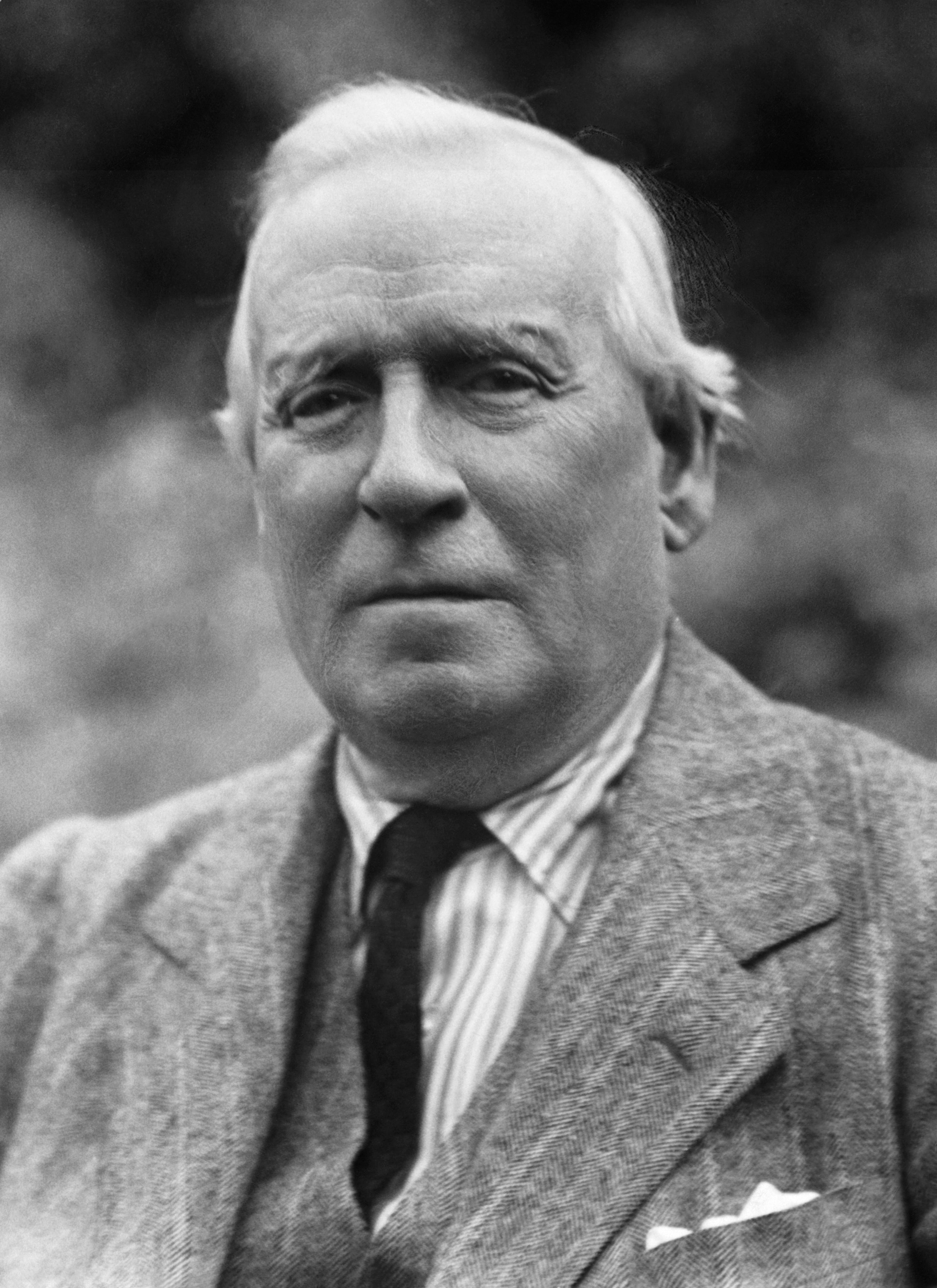

Robert Harris’s enthralling new novel may be one of his three best, and I write as someone who has read virtually all 16 of them. There was 1992’s Fatherland, imagining a world where the Nazis won the Second World War, and 2022’s Act of Oblivion, an epic set in the aftermath of the regicide of Charles I. And now there’s Precipice, in which he has found another slam dunk of a plot. It is based upon the true episode of 60-year-old prime minister HH Asquith’s infatuation with an aristocratic young woman 35 years his junior, to whom he wrote more than 700 letters over a three-year period – sometimes as many as three letters a day.

What makes the story so extraordinary is that Asquith was prime minister during the run-up to the First World War – and throughout those first two catastrophic years of combat – but still found time to compose handwritten notes during cabinet meetings in Downing Street; letters that became increasingly obsessive as the Great War progressed, and that frequently contained the most confidential information on British strategy and affairs of state.

With astonishing recklessness, the married Liberal PM enclosed top-secret dispatches from ambassadors, generals and royals to engage his paramour.

The Hon Venetia Stanley, daughter of Lord Sheffield, was an unlikely recipient of his ardour: a lively, barely educated, time-rich socialite, living at home with her parents between two stately homes and a Mayfair mansion, awaiting a suitable husband. Today she would probably be an Instagram influencer, entitled but enticing.

Remarkably, the letters from Asquith still survive, and Harris uses his actual correspondence throughout – dozens of sentimental, yearning missives addressed to “My darling love … I love you more than words can say, with every fibre, and whatever I have that is worth having and giving”; Venetia’s replies to Asquith do not survive, since he destroyed them all on his final day in office, but Harris does a convincing job of recreating them.

Their passionate correspondence, and the fact of their friendship, was suspected only by their innermost circle. Privacy was easier to maintain in those days. If the prime minister today took up with a young woman less than half his age, the headlines would be merciless: “Pervy PM’s pash on aristobabe”. Or “Prime minister groomed posh bird with 700 steamy letters”. And in no time, there would be censorious newspaper columns citing power imbalance, safeguarding in Downing Street, and the rest.

Harris’s cleverness lies in his psychological sophistication, carrying the reader along the twists and turns of this dubious love story, while the greater drama of the war in the trenches, vast casualties and the disastrous landing at Gallipoli plays off stage. There is an excellent cast of supporting characters: Winston Churchill, perpetually reckless and hungry for war; Lloyd George, ambitiously untrustworthy; the poet Rupert Brooke, dating an Asquith daughter; the artist John Lavery in war-artist mode; King Edward VII, by whom Asquith is appointed PM at a casino in the south of France.

Intriguingly, we are never told whether the Asquith-Stanley relationship ever became sexual. It was challenging in pre-war Britain for an aristocratic single girl to spend time alone with any man, and when they were prime minister, more difficult still.

It is hinted that they may have spent a sexy hour alone in a grassy hollow in the woods at Penrhos, the castellated Stanley estate near Holyhead, Wales, but Harris’s novels seldom include graphic bedroom action. He implies that their sexual relationship may have stopped at frottage, popular amongst the landed classes at the time, which involved the woman exciting the clothed man through his trousers, with vigorous friction until he found relief; the woman was frequently pleasured in a similar style, thus avoiding the danger of pregnancy.

Harris is masterful at authentic dialogue, across all classes. There is not a false note in this novel. He also explains the mechanics of covert communication in this pre-email, pre-text, pre-WhatsApp, pre-Paula Vennells world. The Post Office in 1914 provided twelve collections and deliveries of letters per day in London, and generally three per day in the countryside, and Stanley and her maid spend much time hanging about the letterbox, waiting for the latest love bomb from the prime minister.

One of the great injustices about Harris’s vast oeuvre is that he has won almost no major literary prizes. Infinitely more informed than most Booker winners, and at least as emotionally perceptive, with a historical gravitas worthy of the Duff Cooper Prize – which goes to superlative non-fiction works, including history – his books slip down a crevice in between: too popular and enjoyable for the Booker, too readable and part-fictional for the Duff Cooper. There is something very British about constantly inventing new, and ever more niche, literary awards to applaud books that sell modestly, at the expense of big, quality blockbusters that shift by the truckload.

If Harris’s novels formed part of the school history syllabus, they could inspire a whole generation for whom history is drudgery.

‘Precipice’ by Robert Harris is published on 29 August by Hutchinson Heinemann