A rock formation that spans Ireland and Scotland may be a rare record of snowball Earth – a crucial moment in planetary history when the globe was covered in ice.

The Port Askaig Formation, which is made up of layers of rock up to 1.1km thick, was likely to have been laid down between 662 and 720 million years ago during the Sturtian glaciation, research suggests.

This was the first of two global freezes thought to have triggered the development of complex life.

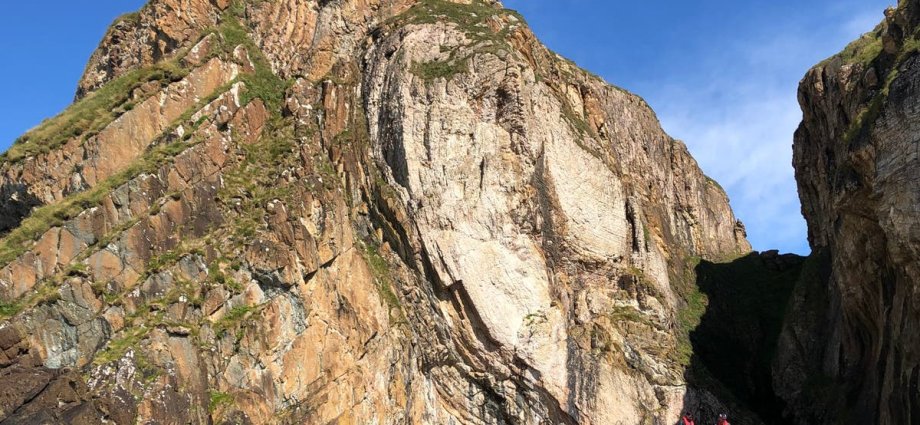

According to the new study, one section of exposed rock, found on Scottish islands called the Garvellachs, is unique as it shows the transition into snowball Earth from a previously warm, tropical environment.

Other rocks that formed at a similar time, like some in North America and Namibia, are missing this transition.

Therefore researchers believe their findings may be the world’s most complete record of snowball Earth – a theory that suggests Earth’s oceans and land surfaces were covered by ice from the poles to the Equator during at least two extreme cooling events between 2.4 billion and 580 million years ago.

Senior author Professor Graham Shields, of University College London (UCL) Earth Sciences, said: “These rocks record a time when Earth was covered in ice.

“All complex, multicellular life, such as animals, arose out of this deep freeze, with the first evidence in the fossil record appearing shortly after the planet thawed.”

First author Elias Rugen, a PhD candidate at UCL Earth Sciences, said: “Our study provides the first conclusive age constraints for these Scottish and Irish rocks, confirming their global significance.”

He explained that most areas of the world are missing the layers in the rocks that record a tropical environment and mark the transition, because the ancient glaciers scraped and eroded away the rocks underneath.

“But in Scotland by some miracle the transition can be seen,” Mr Rugen said.

Lasting some 60 million years, the Sturtian glaciation was one of two big freezes that occurred during the Cryogenian Period – between 635 and 720 million years ago.

For billions of years before this, life consisted only of single-celled organisms and algae.

After this period, complex life quickly emerged, with most animals today similar in fundamental ways to the types of life forms that evolved more than 500 million years ago.

One theory is that the hostile nature of the extreme cold may have prompted single-celled organisms to co-operate with each other, forming multicellular life.

The advance and retreat of the ice across the planet was thought to have happened relatively quickly, over thousands of years, because of the albedo effect – that is, the more ice there is, the more sunlight is reflected back into space, and vice versa.

Prof Shields explained: “The retreat of the ice would have been catastrophic. Life had been used to tens of millions of years of deep freeze.

“As soon as the world warmed up, all of life would have had to compete in an arms race to adapt. Whatever survived were the ancestors of all animals.”

For the new study, the research team analysed samples of sandstone from Port Askaig Formation as well as from the older, 70-metre thick Garbh Eileach Formation underneath.

The researchers said the new age constraints for the rocks may provide the evidence needed for the site to be declared as a marker for the start of the Cryogenian Period.

This marker, known as a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), is sometimes referred to as a golden spike, as a gold spike is driven into the rock to mark the boundary, and these sites attract visitors from around the world.

The study, led by UCL researchers, is published in the Journal of the Geological Society of London.