Remarkable new scientific research at Stonehenge has revealed an extraordinary new mystery.

Mineralogical tests on the massive six-tonne stone at the heart of the monument show that this central rock, known as the altar stone, was brought to Stonehenge from the far north of Scotland.

The altar stone is arguably the most ritually important stone in Stonehenge, because it is the rock that marks the intersection of the prehistoric temple’s two most important celestial alignments – the winter solstice sunrise to summer solstice sunset alignment, and the summer solstice sunrise to winter solstice sunset alignment.

It’s already known that some of the monument’s smaller stones were brought to the site from southwest Wales, around 120 miles away. But moving a rock from northern mainland Scotland or Orkney would have involved a journey of well over 500 miles.

The discovery has huge implications, and is likely to transform archaeologists’ perceptions around key aspects of life in prehistoric Britain. Up to now, most scholars have assumed that British Neolithic society was exclusively local or regional (based on tribal, clan or similar identities), but the newly discovered Stonehenge-Scotland link, when combined with the Welsh origin of some of the Stonehenge stones, suggests that there might also have been a pan-British aspect to how Neolithic Britons lived.

The newly revealed Scottish link implies that 4,500 years ago, there was already at least some political and religious cooperation across Britain. That’s because the Neolithic people who transported the six-tonne rock from northern Scotland or Orkney to southern England must have known that Stonehenge existed, that it was being expanded, and precisely what shape and size of giant rock was required. That suggests geopolitical cooperation, or even some religious commonality.

Another aspect of the new discovery is the southern British Neolithic choice of northern Scotland, potentially Orkney, as a symbolic partner in Stonehenge’s construction. It is conceivable that this was because Wiltshire and Orkney were arguably Britain’s two most advanced Neolithic cultures. The fact that despite being at opposite ends of Britain, they now appear to have been well aware of each other’s existence and appear to have developed geopolitical and religious links, has far-reaching implications that will profoundly change scholars’ views of the nature of prehistoric Britain.

But the new discovery of the Scottish link is not just important from an ancient geopolitical perspective. It will also transform perceptions of British Neolithic maritime technology.

Dragging a six-tonne rock across mountains, hills, valleys and at least 30 rivers for well over 500 miles (in practice probably at least 700 miles) would have taken several years to accomplish – so it seems relatively unlikely that the rock was brought over land from northern Scotland to Wiltshire. It’s far more probable that it was brought by sea, a journey that would have taken just a few months.

Up till now, many prehistorians would have assumed that seaworthy craft capable of safely carrying such a massive load would not have existed in Neolithic Britain. What’s more, the stone would almost certainly have been accompanied on its journey by a large team of mariners, priests and others – so it’s conceivable that it proceeded south as part of a substantial flotilla.

The North Sea is often far from calm, so the craft would have needed to deal with some relatively choppy waters, and of course the flotilla’s navigators would have needed to have prior knowledge of the coastline of at least eastern Britain.

It’s likely, therefore, that the flotilla proceeded south, hugging Britain’s east coast for some 700 miles, and then turned west into the Thames estuary, along the Thames and part of the Kennet until Newbury or possibly Hungerford, where the rock would have been unloaded and then dragged (on a sledge or on rollers) for at least 30 miles to its final destination, Stonehenge.

But why did the Neolithic builders of Stonehenge want a northern Scottish (or Orkney) rock as the symbolic centre of their spectacular southern British stone temple? At present there is no way of knowing for certain the answer to that question. However, it is possible that the concept of stone circles was first developed in Orkney – and that somehow the builders of Stonehenge were aware of that.

It is therefore conceivable that they wanted to ensure that the central feature of their new monument came from Orkney. Indeed, it is possible that the six-tonne rock had been chosen specifically for its religious significance – and that it had formed part of a major stone circle in Orkney.

No doubt, archaeologists will be investigating that possibility – not least because the great rock brought well over 500 miles to Stonehenge is roughly the same size and shape as some of those used in the construction of stone circles in Orkney.

So perhaps the builders of Stonehenge were deliberately paying homage to what they might have perceived to be their great temple’s ideological/theological ancestor.

It also suggests that the builders of Stonehenge viewed their great monument as a composite temple made up of components from across a much wider geographical and ideological landscape, symbolically and perhaps even spiritually incorporating several different parts of Britain (certainly including Wales and mainland Scotland or Orkney).

But are there other exotic components to Stonehenge that have yet to be discovered? Archaeologists will now be on the lookout for just such features.

“The fact that Stonehenge’s altar stone appears to come from mainland Scotland or Orkney has substantial implications for our understanding of Stonehenge itself and of Neolithic society in general,” said one of the key scientists involved in the research, Dr Robert Ixer, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Archaeology in London.

“It completely rewrites the relationships between the Neolithic populations of the whole of the British Isles,” he further told The Guardian. “The science is beautiful and it’s remarkable, and it’s going to be discussed for decades to come … It is jaw-dropping.”

The research has been carried out by scientists from Aberystwyth University, London’s Institute of Archaeology, and Australia’s Curtin and Adelaide universities, and is being published today in the UK-based scientific journal Nature.

But it was a British geologist at Curtin University who did the crucial research, pinpointing a northern Scottish/Orkney origin for Stonehenge’s central stone.

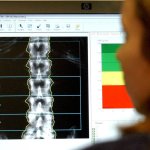

They identified the stone’s mineralogical fingerprint (and crucially, the geological ages of that fingerprint – ranging from around 3 billion to around 460 million years), which showed that the closest match by far was the extreme north of Scotland (including Orkney).

“It’s been a two-year voyage of discovery for me and my colleagues. We collated more than 500 ages for the minerals within the altar stone, and it was those ages which, when correlated, gave us the crucial chronological fingerprint which revealed the northern Scottish origin of the rock,” said Anthony Clarke, the British geologist who carried out the crucial research at Curtin.

Of all the ancient sites in Britain, Stonehenge really is the mystery that keeps on giving.