Mysterious carvings deciphered at the Göbekli Tepe archaeological site in Turkey suggest the world’s oldest monument – about twice as old as Stonehenge – is a solar calendar built to memorialise a devastating comet strike.

A new study published in the journal Time and Mind on Tuesday indicates that Göbekli Tepe, a 12,000-year-old temple-like complex containing carvings of intricate symbols, was constructed to record an astronomical event that sparked the dawn of human civilisation.

The world’s first calendar, made around 9,000BC, enabled people to observe the sun, moon and constellations in order to keep track of time and mark the change of seasons, scientists from the University of Edinburgh say.

“It appears the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe were keen observers of the sky, which is to be expected given their world had been devastated by a comet strike,” Martin Sweatman, a co-author of the study, says.

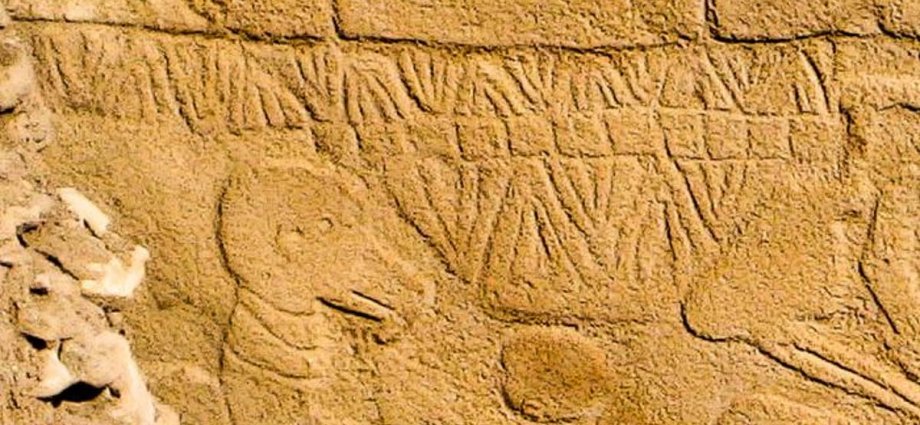

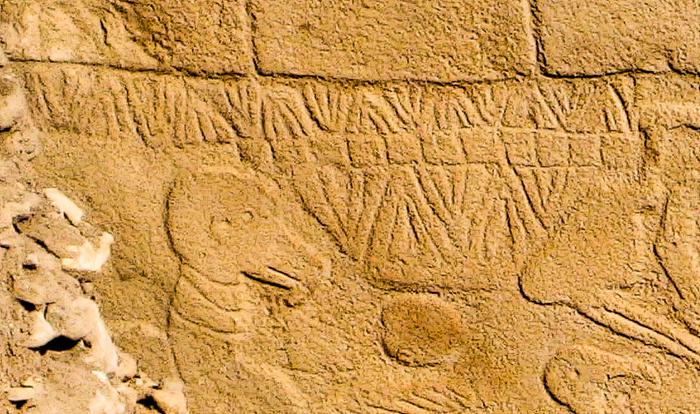

The researchers say the strange V-shaped symbols carved onto pillars of the 15-metre-tall Göbekli Tepe could each represent a day.

Using this interpretation, scientists counted a solar calendar of 365 days on one of the pillars, consisting of 12 lunar months plus 11 extra days.

The summer solstice was represented by a special symbol, a V worn around the neck of a bird-like beast.

Researchers suspect the other symbols at the site with similar V-markings at their necks likely represent deities.

As the prehistoric monument tracks the phases of the moon as well as the cycles of the sun, archaeologists believe the carvings represent the world’s earliest “lunisolar calendar”, predating every known calendar by many millennia.

The calendar was likely developed to record the date when a swarm of comet fragments hit the Earth some 13,000 years ago, scientists say.

Such a comet strike is known to have ushered in a mini Ice Age that lasted over a millennium and wiped out many species of large animals.

The devastating strike could have sparked a lifestyle shift among early humans from hunting-gathering to agriculture and the birth of civilisation in the Fertile Crescent of West Asia, researchers say.

A previous study found that a cluster of comet fragments that hit the Earth nearly 13,000 years ago likely shaped the origin of human civilisation.

The 2021 study, published in the journal Earth Science Reviews, suggested that the Fertile Crescent, spanning modern Egypt, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, switched from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to farming around this time, creating permanent settlements.

There’s a substantial body of evidence from four continents supporting the theory that a comet hit the Earth around this time.

Analysis of soil sediments in North America and Greenland, where the largest fragments are thought to have hit, found excess levels of platinum and nanodiamonds as well as signs of materials melted by extremely high temperatures.

Adding strength to this theory, the latest study found a pillar near the Göbekli Tepe site that appears to picture the Taurid meteor stream.

The Taurid shower, coming from the direction of constellations Aquarius and Pisces, is thought to be the source of the comet fragments which rained on the planet for 27 days.

Scientists suspect the monument remained important to the ancient people for millennia, suggesting the comet impact event influenced the development of human civilisation.

“This event might have triggered civilisation by initiating a new religion and by motivating developments in agriculture to cope with the cold climate,” Dr Sweatman says.

“Possibly, their attempts to record what they saw are the first steps towards the development of writing millennia later.”