Complex life forms might have originated on Earth’s oceans about 1.5 billion years earlier than previously thought, according to a new study.

Previous studies suggest animal life did not emerge on Earth until around 635 million years ago, mainly constrained by the availability of the element phosphorous.

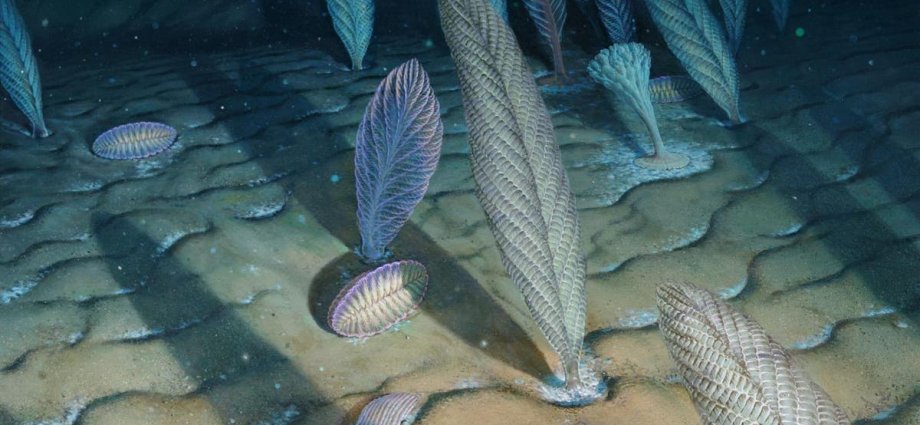

Then in the Ediacaran era, about 635 million to 541 million years ago soft-bodied animal-like life forms emerged as dissolved sea water phosphorous concentration increased following intense global tectonic activities.

The latest research, published in the journal Precambrian Research, however, claims to have found likely signs of complex animal life beginning even as early as 2.1 billion years ago.

Researchers, including those from Cardiff University, suspect the unexplained formations in the nearly 2.5 km-thick sedimentary deposits they discovered in Franceville, Gabon could contain fossils of such early life forms.

However, they say these cryptic life forms likely died out before they could spread globally.

In the study, scientists analysed the strange ancient rock formations in Gabon, to understand whether they contained elements showing signs of life such as oxygen and phosphorous.

They found evidence that there was a sudden intense pulse of phosphorous-rich water pouring into a section of the ocean floor, and creating a reservoir where early complex life could have emerged.

“We propose that this previously unrecognised local pulse in dissolved seawater P concentration, of comparable magnitude to Ediacaran seawater levels,” researchers wrote in the study.

They say that over two billion years ago the rock sediment uncovered in Gabon was part of the sea floor cut off from the global ocean that sustained stable quantities of phosphorous and oxygen.

These elements were likely concentrated in the rocks from the collision of continental plates underwater and volcanic activity, scientists say.

Such conditions could have created a “nutrient-rich shallow marine inland sea” and provided a “laboratory” for complex life forms to evolve, researchers suspect.

“Nutrient enrichment initiated localized emergence of large colonial macrofossils,” they wrote in the study.

Those conditions may have been favourable for primitive organisms to grow larger, showing more complex behaviour, scientists speculate.

However, since the sediment was isolated and cut off from the ocean, it may not have had enough nutrients to sustain a food web, they say.