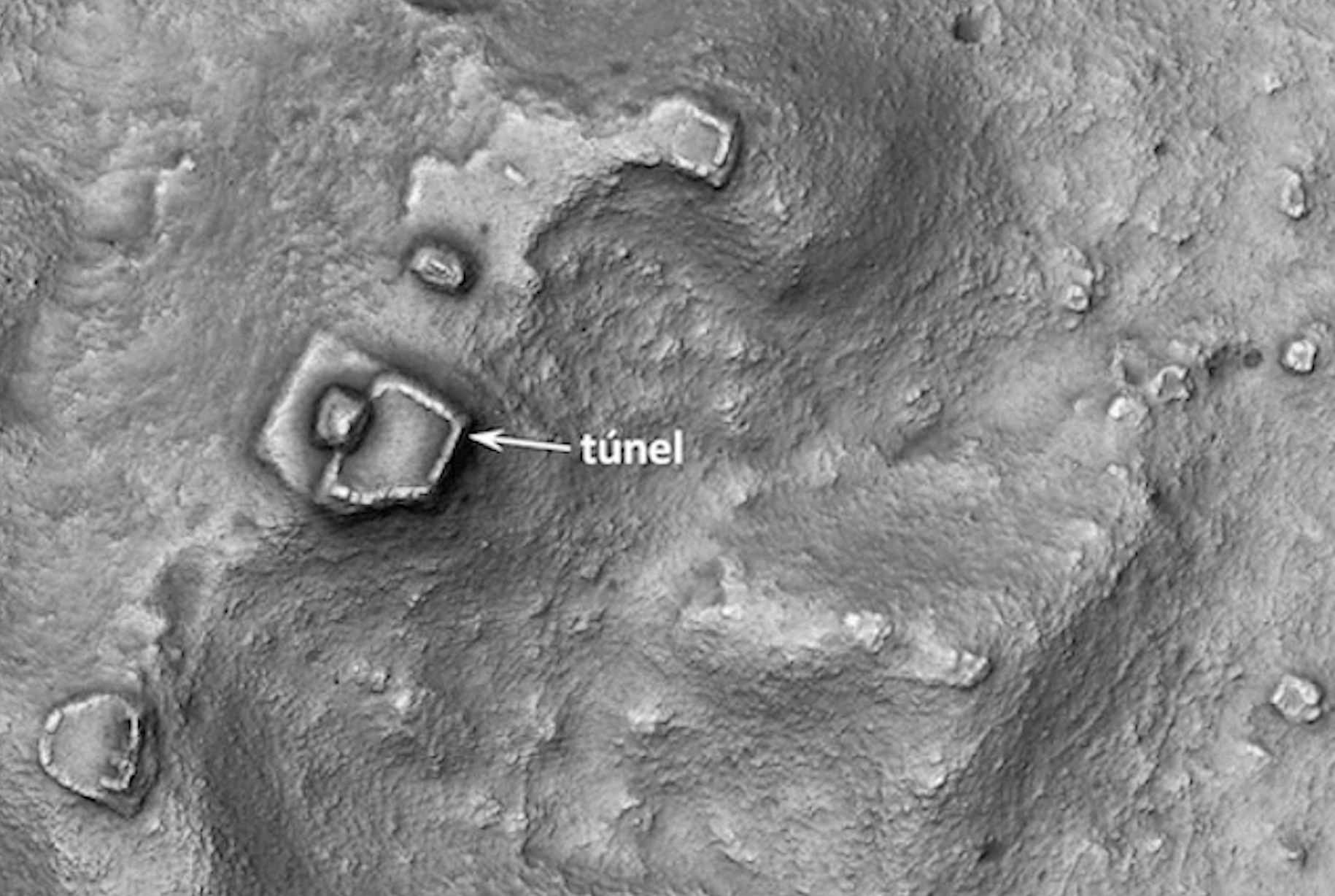

Archaeologists have unearthed a mysterious underground structure with painted walls beneath a Mayan ball court in Mexico.

They were using advanced aerial laser scanning techniques to see what was beneath a previously uncovered ancient ball court in Campeche, Mexico, and stumbled upon the mysterious structure.

The exploration focussed on a nearly 140 square kilometre patch of land in the Balam Kú Biosphere Reserve.

The structure, dated to the Early Classic period of the Mayan civilisation between 200 and 600 AD, could offer insights into life on the South American continent before the Spanish conquest, according to a statement from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.

“We located parts of an earlier building that had painted walls. But only further excavations may reveal the shape of that underlying building and what its function was,” archaeologist Ivan Šprajc from the Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies told LiveScience.

“The inevitable impression is that the Mayan culture of this region that we have just explored, was noticeably less elaborate than in the Petén, to the south, and the regions of the Chenes and Chactún, to the north and east.”

Researchers suspect the structure may have been “important” during its heyday since ball courts are normally found only at major Mayan sites and are centres of the regional political organisation.

They said the ancient site may have seen its highest occupation during the Late Classic and Terminal periods, around 600-1000 AD, due late migrations and population growth in the neighbouring more favourable regions.

At another nearby site, archaeologists uncovered an ancient 15-metre-high pyramid and a water reservoir.

On top of this pyramid structure, researchers found artefacts, including ceramic vessels, a ceramic animal leg – likely of an armadillo – and a flint blade.

These artefacts, which were likely left as offerings, were dated to about 1250-1524 AD in the Late Postclassic period shortly before the Spanish conquest.

Researchers said the items found on top of the pyramid suggest a weakened population’s presence long after the Central Lowlands suffered political disintegration and drastic demographic decline in the centuries before the Europeans arrived.