In 1796, when the sixth emperor acceded, the Qing presided over a third of the world’s population and one of the most prosperous empires in history. In 1912, the 11th and last emperor abdicated, aged 12, ending 2,000 years of dynastic rule, and paving the way for the modern Chinese republic. The period in between is China’s “long 19th century”, said Laura Cumming in The Observer. Marked by famines, foreign invasions and savage wars, in which tens of millions of people died, it has also been dubbed the “hidden century”, because the period was considered so dark and violent that cultural histories have “skated right over it”.

But now, in a world first, the British Museum has brought together 300 objects from the era, based on the intensive research of some 100 scholars, and the result is “enthralling”. We see everything from exquisite embroidered robes and “a pair of imperial vases so gigantic they dwarfed the emperor”, to the “handprint with which an illiterate worker once signed a contract”. There is a “fragment” of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, looted and destroyed by British and French troops in 1860, and beside it, a sentimental portrait of a tiny dog brought back for Queen Victoria. Believed to be the first Pekingese to arrive in Britain, it was punningly named Looty.

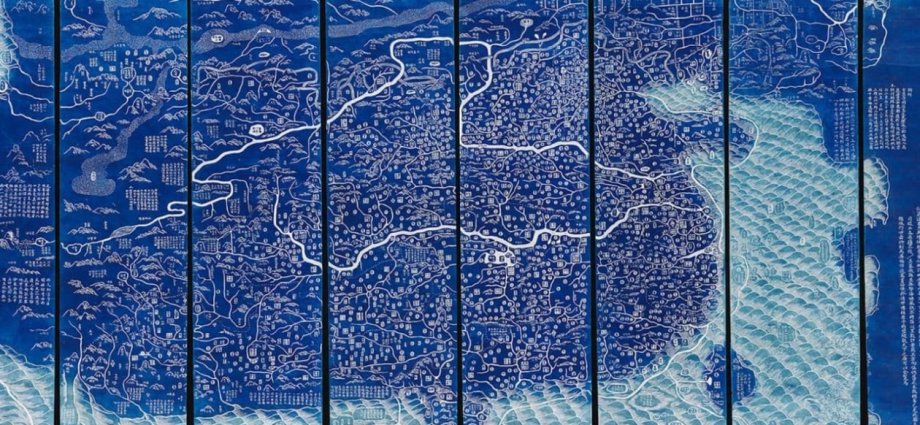

What is made startlingly clear in this “dumbfounding” exhibition is the “cynical” role that Britain played in the decline of imperial China, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. One of the items on show is an 1851 lithograph of a depository stacked to the roof with Indian opium bound for export to China. It was China’s efforts to stop this devastating trade that led to the Opium Wars (in which the Summer Palace was destroyed) – the first direct military confrontation between China’s “time-hallowed civilisation”, with its medieval armoury, and the “industrial” West, with its modern guns.

How could China, where gunpowder was invented, have been humiliated by “Queen Victoria’s drug dealers”? One answer is hinted at in a case containing a labourer’s garment, made from rice-fibre and palm. It evokes the millions who were toiling in poverty, a world away from the closed confines of the “bejewelled” imperial court, a place where nothing seemed to have changed for centuries.

It’s a big show that seeks to compress a complicated period, said Laura Freeman in The Times. And the task of taking it all in is made more difficult by the irritating audio tracks that play on a loop, of ghostly Chinese voices and cockerels crowing. My advice is to trot through it all, to get a gist of the history, then go back and focus on just a few objects, perhaps the hanging scrolls decorated with antique vessels, or the “handsome thumb rings worn by Manchu archers”. This “curiosity shop” is overstuffed, but it contains many individual items of “extraordinary beauty”

British Museum, London WC2 (020-7323 8299; britishmuseum.org). Until 8 October