A “blazing, once-in-a-generation talent”, Martin Amis “provoked, inspired and outraged readers … across a literary career that set off like a rocket, and went on to dazzle, streak and burn for almost 50 years”, said Boyd Tonkin in The Guardian.

He wrote 15 novels, as well as journalism and essays that stretched from “an account of arcade video games, through literary studies and critiques of pop culture, to a meditation on Stalin’s crimes: Koba the Dread {2002}”.

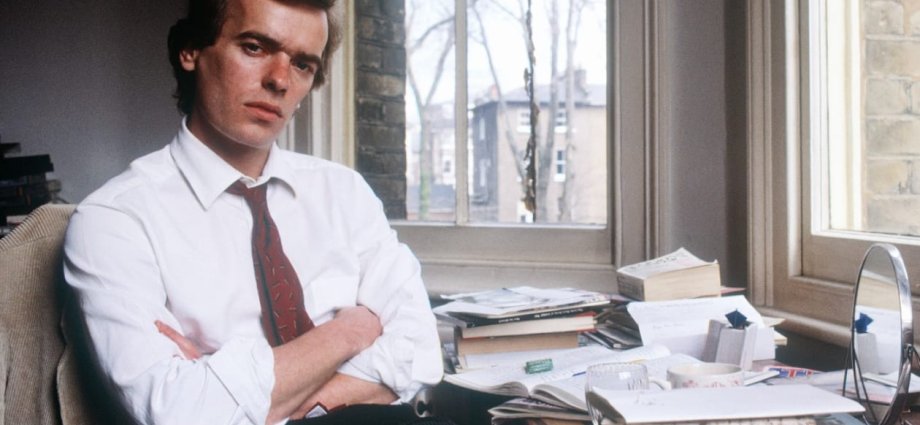

For years, he was rarely out of the headlines, said The Daily Telegraph – with his “flamboyant lifestyle”, complete with glamorous girlfriends and roistering literary confrères, often attracting as many column inches as did “the pyrotechnics of a prose style that divided the critics more than any other contemporary writer”. His face stared moodily out from countless newspaper profiles, many of which described him as having the presence and swagger of a rock star. (He was most often likened to Mick Jagger.) Even the state of his teeth became the object of fascination.

Rarely short of a controversial opinion, he was accused of everything from misogyny and Islamophobia to greed, arrogance and treachery. “To his detractors, he was a stylist in a continual – and fruitless – search for a grand theme; his plots were unnecessarily convoluted, his characters close to caricature and his virtuoso prose more suited to straight satire than to the deeper themes he tried to address.”

Although they were close, his father, Kingsley Amis, joined in the criticism, deploring the way Amis, with his postmodern flourishes, “buggered about with the reader”, as he put it. “I admire his intelligence and discipline,” he said, “but there’s a terrible compulsive vividness about his style … that constant demonstrating of his command of English.” His admirers, however, were having none of this. Awed by his verbal dexterity, his acid wit, and the incisiveness of his criticism, they saw him as “the unfortunate target of jealous and inferior rivals”. “Every writer under 45 would secretly like to be Martin Amis,” said the novelist Will Self.

A turbulent childhood

Martin Amis was born in 1949, the second of three children to Kingsley Amis and his first wife Hilly (Hilary Bardwell). Kingsley was then a struggling academic. But in 1954 he published “Lucky Jim”, and their lives changed. When Martin was nine, the family moved to the US, so that Kingsley could take up a fellowship at Princeton; during that time, Martin was “interfered with” by a stranger at a party. About three years later, his father fell in love with the writer Elizabeth Jane Howard, precipitating the collapse of his marriage. Hilly was devastated. After that, Martin, who’d always been wayward (he’d started smoking at ten), moved from school to school, at one point taking months out to appear in a film, “A High Wind in Jamaica”. Until he was 17, he mainly read comics and was “pretty illiterate”. It was Howard who introduced him to literature, and sent him to a crammer, whence he won a place at Oxford. There, he discovered that though he was not a tall man {5ft 6in}, he had no trouble attracting high-achieving women – his early girlfriends included Tina Brown.

Graduating with a first, he found a job at the Times Literary Supplement; in 1975, he moved to The New Statesman, where he worked alongside Julian Barnes and Christopher Hitchens, who became his lifelong friend. His name, he admitted, had opened doors. A competition for the least likely book title was said to have had the entrant: Martin Amis, My Struggle. He published his first novel “The Rachel Papers” – about a sexually obsessed young man not unlike himself – in 1973 when he was 24. He had started writing because he wanted to “join the dance”, he said on “Desert Island Discs” in 1996. “What is being redeemed is the formlessness of life. It would be intolerable to me to just be a passive liver of my life.” His debut won the Somerset Maugham Award – the only major fiction prize he won.

Even then, said Boyd Tonkin, there was the sense that he was “too short, too clever, too entitled”. But close friends did not recognise the portrait of the artist as sneering seducer: they knew a man who was funny, kind and sensitive; and who spent most of his time not drinking with his cronies but engaged in serious work. Visitors to his flat would remark on the dartboard and pinball machine; if they’d looked harder, they’d have also spotted “neat editions of Bellow and Nabokov, twin touchstones of his art, on the shelves”.

The London trilogy

In 1984 he skewered the Thatcher era in his widely acknowledged masterpiece “Money”, which is narrated by John Self, a semi-literate ad director with a gargantuan appetite for booze, pills, porn and junk food. Five years later (by which time Amis had married Antonia Phillips, and had two sons) he produced “London Fields”, the second book in the “London trilogy”. A blackly comic tale set in a decaying London, it is about a murderee, Nicola Six, in search of her killer, and has a cast of low-lifes, including Keith Talent, who looks like a “murderer’s dog”. It failed to make the Booker shortlist because two judges objected to the way Amis portrayed women. In 1991, however, he was shortlisted for “Time’s Arrow”, which recounts, in reverse, the life of a doctor who worked for the Nazis.

In 1994 he caused uproar – and lost friends – by sacking his agent Pat Kavanagh, who was married to Julian Barnes, and hiring Andrew “The Jackal” Wylie, who won him a £500,000 advance for “The Information” By this time, his marriage had ended and, a few years later, following more negative headlines about the cost of having his teeth fixed, he moved to Uruguay (and later New York) with his new wife, the writer Isabel Fonseca. He had two daughters with her; and was also delighted to find that he had another daughter, from a relationship years earlier.

In 2000, he published a memoir, “Experience”, in which he discussed the discovery that his cousin and childhood playmate Lucy Partington, who had disappeared in 1973, had been murdered by Fred West. It was warmly received; but the reviews of his later novels (Yellow Dog; Lionel Asbo) were scathing. Amis was philosophical about his waning popularity. “There’s a one-word narrative for every writer,” he told an interviewer. “For Hitchens, it was ‘contrarian’. For me, it’s ‘decline’.”

As for his legacy, it was too soon to tell, he said. “Writers don’t realise how good they are because they are dead when the action begins: with the obituaries. And then the truth is revealed 50 years later by how many of your books are read. You feel the honour of being judged by something that is never wrong: time.”