Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest types of cancer. This is largely due to the fact that pancreatic cancer symptoms typically don’t arise until the late stages of the disease, making many patients ineligible for the current best treatment method, which is surgery to remove any tumours.

Even in patients who have tumours removed, there’s often a really high chance of the cancer returning.

But the results of a recent study suggest that the immune system could be a useful tool in treating pancreatic cancer. The research, which was published in Nature, showed a personalised cancer vaccine was able to stimulate the immune system in half of the patients who received it.

This heightened immune response was also still detectable in these patients a year and a half later.

In order to understand how this pancreatic cancer vaccine works, it’s important to first understand the role that the immune system plays in preventing cancer.

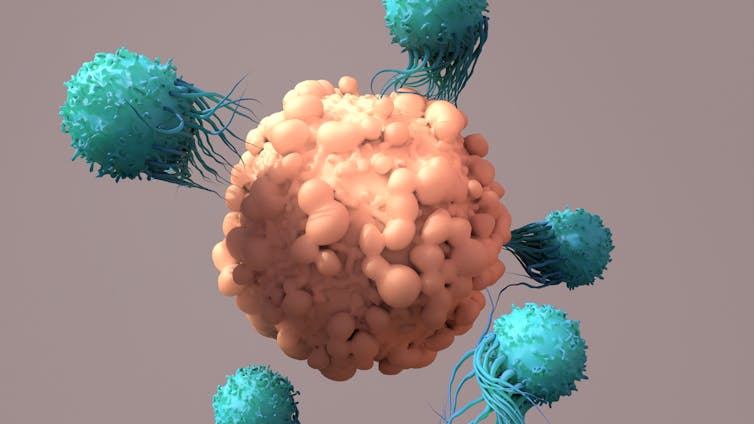

Our immune system is often very well equipped to fight cancer. But unfortunately, cancer cells contain certain protein receptors whose purpose is to help them hide from our immune cells – effectively preventing our immune system from destroying them.

However, scientists have found a way to block these receptors, so the immune system is able to recognise cancer cells as a threat again and remove them.

This is what immunotherapy – one of the newest techniques for treating cancer – does. These therapies work by harnessing the power of the immune system.

There are a few different types of immunotherapies, but a new one that is promising against cancer is the use of mRNA vaccines. These use genetic material in order to stimulate the immune system.

Scientists first begin by taking the genetic material of cancer cells and identifying the most mutated parts of the DNA – so-called neoantigens – before putting them in between a strand of mRNA.

If we think of DNA as the hard drive, mRNA is sort of like the software of our cells. It’s function is essentially to copy and carry genetic instructions from our DNA to other parts of the cell.

This mRNA is then given to patients as a personalised vaccine. It’s personalised because everyone has different neoantigens, so everyone receives slightly different vaccines with slightly different mutations encoded into the mRNA strand.

Once injected into the patient, the mRNA then makes a little bit of the cancer – just enough to stimulate the immune system. The idea is that the person’s immune systems will then react to the cancer and give them protection.

This is how the recent pancreatic cancer mRNA vaccine was developed. The pharmaceutical company BioNtech created personalised mRNA vaccines for 16 participants using cells from their recently removed tumours.

Design_Cells/ Shutterstock

The patients were all treated with this personalised vaccine, alongside another form of immunotherapy (the drug atezolizumab) followed by aggressive chemotherapy.

Half of the patients treated with the vaccine and immunotherapy combination saw an increase in a specific type of immune cell (called a T cell, which is known to protect against cancer). This showed the researchers that for at least some participants, their immune systems might be learning to fight the cancer.

At an 18-month follow-up, the patients who’d seen the increase in T cells still had signs of improved immune response. Most also had no signs of their cancer recurring.

The authors concluded that it may be because the immune system was successfully stimulated which helped stop the cancer returning. The mRNA vaccine was also well tolerated by patients with no obvious major side effects.

Immune function

While this trial’s findings are intriguing, its numbers are too small to draw any major conclusions. It will be necessary for larger trials to be conducted including randomised studies.

This would see only some of the participants receive the vaccine, allowing researchers to truly understand what effect it has – and whether the vaccine really does what it’s supposed to do, which is stimulate the immune system and improve time before recurrence (and ultimately survival).

This would also allow them to see whether the vaccine had a distinct effect, and that this effect wasn’t just down to the other treatments or immunotherapy the participants received.

It’s promising to see that we may have a new type of therapy to investigate for treating pancreatic cancer. These findings also highlight the potential of mRNA vaccines as a cancer treatment more broadly – building on the results of another study from last year which showed an mRNA vaccine to be effective against melanoma.

![]()

Justin Stebbing is editor-in-chief of Oncogene. His conflicts are listed here and none are relevant to this piece:

https://www.nature.com/onc/editors