Plants may appear silent, indifferent organisms to us, but recent research has found they make high-pitched clicking sounds when they are struggling to find water. In principle, neighbouring plants could pick up on and react to these noises.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

Scientists in Israel record brief pulses of sound coming from tobacco and tomato plants in a greenhouse. They happened more often when the plants had not been watered or at times when they were losing large amounts of water from their leaves.

The sounds were about as loud as a quiet conversation but were mostly between 40,000Hz and 60,000Hz, which is too high pitched for human hearing which only goes up to about 20,000Hz. However, they should be audible by dogs, who can hear up to 45,000Hz, or cats, whose hearing goes all the way up to 64,000Hz.

Many people think of plants as nice-looking greens. Essential for clean air, yes, but simple organisms. A step change in research is shaking up the way scientists think about plants: they are far more complex and more like us than you might imagine. This blossoming field of science is too delightful to do it justice in one or two stories.

This article is part of a series, Plant Curious, exploring scientific studies that challenges the way you view plantlife.

Although it’s nice to think plants were sending each other messages about a water shortage through sound, this may not have been the case. Instead, the sounds may be due to bubbles forming in the plants’ stems in a simple physical process.

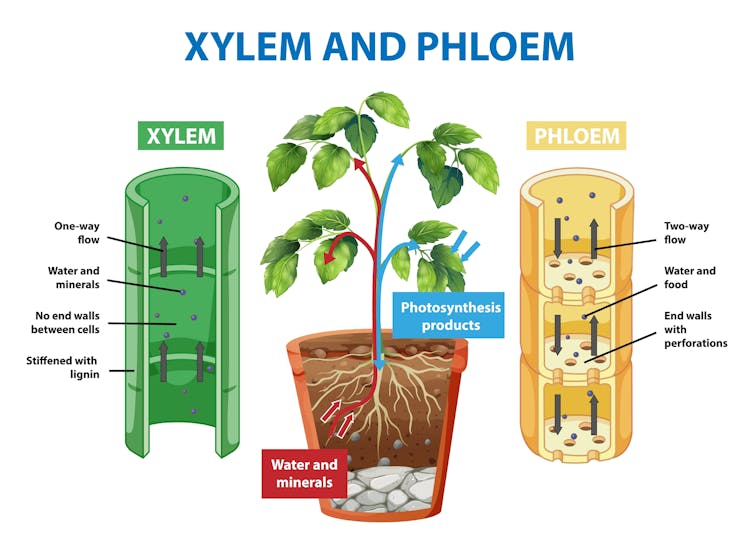

Plants lose water from their leaves by evaporation whenever they are photosynthesising. Rather than actively lifting the water to their leaves, plants cleverly take advantage of the way that water molecules cling to each other.

Water is carried up from the roots in narrow tubes, each filled with a continuous column of water. As each molecule of water evaporates it pulls on the next molecule, which pulls on the next, rather like when you suck a drink through a straw.

BlueRingMedia/Shutterstock

When evaporation from the leaves is greatest, in the middle of the day, or the plant can’t easily get water from its roots because the soil is too dry, the column of water can break. This forms a bubble in the tube.

These are the exact circumstances under which the ultrasonic pulses happened, so it seems the best explanation. Indeed, clicks caused by water columns breaking have often been recorded, and sometimes used to measure how badly plants are being affected by drought.

However, most previous investigations have used microphones fixed to the surface of the plant. In the Israel paper, the sounds were captured by microphones some distance from the plant.

It was the first study to show these clicks can be heard as far as five metres away. This means that even if they aren’t intentional, the clicks could carry information useful to other plants or animals.

Other plants might respond by reducing their water use. For example, shutting down photosynthesis. Nearby insects may realise that the clicking plant is vulnerable to attack.

A different world

Some people may think of plants as passive, but all organisms use whatever sources of information are available to them to adapt themselves to their environment.

In fact, there are many examples of plants sharing information with other plants and with animals. Previous studies of plant “language” have focused on communication through scent in particular.

We know flowers use smell to entice insects to pollinate them. Bumblebees can even distinguish between different floral scent patterns.

Many plants also release airborne chemicals that warn their neighbours when they are attacked by disease or insects. Plants may activate their defences in response, for example releasing toxins and unpleasant tasting chemicals.

There are even examples of plants using chemical messages to summon parasitic wasps that lay their eggs inside caterpillars, or predators that eat spider mites infesting a plant.

But a growing body of evidence is also showing plants can and do respond to sound.

In some flowers, pollen is only released by the vibrations caused by the buzz of bees that are good pollinators. Sound frequencies within the range of human hearing have been found to slow down tomato fruit ripening, and to speed up germination and growth in mung bean seedlings.

One study found pea roots could find their way through a simple maze by following the sound of running water. And relevant to the new findings, white noise helped seedlings of Arabidopsis (rockcress) survive without water.

It isn’t hard to imagine how gathering information about the state of neighbouring organisms could evolve into a system of communication.

For example, it seems likely that the scent signals that help groups of plants coordinate their defences started out as a fast way for one branch of a large plant to tell another that it was under attack, because sending a signal through the air was the shortest route.

It is possible groups of plants could gain an advantage by eavesdropping on chemicals released by their neighbours, from which an information exchange gradually emerged.

Perhaps in a similar way, listening for these sounds of water stress could help other plants to adapt to their environment.

![]()

Stuart Thompson has received funding from MAFF and the Nuffield Foundation and has consulted to the University of Copenhagen.