When disaster strikes, it’s helpful to know what’s going on. This is why the UK government has launched an emergency alerts service, to be used in life-threatening situations including flooding and wildfires.

The time has now come to test how the system works – which is why every mobile phone in the UK will get an emergency alert on Sunday, 23 April at 3pm. The message, which will appear alongside a loud alarm and vibration on millions of phones, will let the government see how this new public warning system operates. Your phone will vibrate and make a loud siren-like sound for about ten seconds – even if it’s on silent.

Similar systems are already in place in countries such as the US, Australia, France and Japan. But while these alerts can make a big difference in emergency situations, they also raise serious privacy concerns which might tempt some people to opt out from the messages.

Domestic violence charities have also expressed concern that the message and loud alarm may alert abusers to secret phones that some people experiencing violence in the home may have hidden. Women’s Aid and Refuge have both issued advice on how to turn the alerts off if you’re hiding a secret phone.

National alert systems use cell broadcasting technology, which allows messages to be sent to all mobile devices within a defined area without knowing their phone numbers or locations.

In essence, the cell broadcast system is a computer that checks the message, makes sure it’s secure and valid, and then sends it via special radio signals to all the radio towers that cover the area where the message is meant to go.

Crucially, the message is not sent to individual phone numbers, but to groups of phones that are in the area – much like making an announcement via loudspeaker in a stadium full of people.

Fears have been expressed that cell broadcasting could enable mass surveillance by revealing who is in a certain area at a certain time. Or by allowing authorities to track people’s movements across different areas. But are these worries really justified?

Phones at risk?

The Cabinet Office has stated that the service does not require any personal information such as someone’s identity, location, or telephone number. Nonetheless, research shows that privacy issues can happen even when personal information is not collected.

It’s possible, for example, that hackers could intercept an emergency alert system if the alerts are not encrypted or authenticated properly, or if there are vulnerabilities in the devices or networks that receive them. Indeed, warnings about lack of security and potential hacks have been raised in the US around their emergency alerts system.

It’s also possible that scammers could use the opportunity to send false alerts to phones that include bogus links. The official alert won’t include any links or requests to reply.

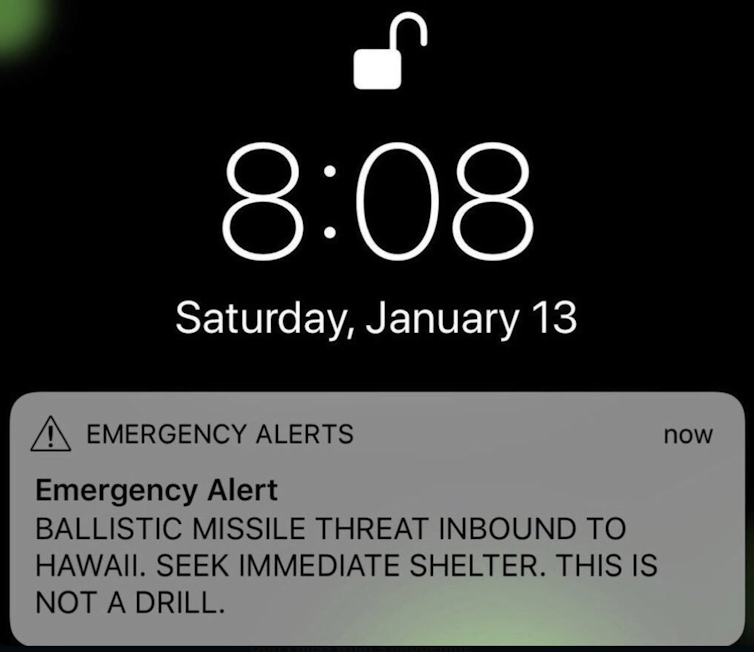

And of course, alerts can be sent in error. In 2018, widespread panic was witnessed in Hawaii after an early-morning emergency alert mistakenly warned of an incoming ballistic missile attack.

Hypothetically speaking, it may also be possible to profile people through an alert system. If someone acknowledges an alert quickly or follows the instructions in the alert, it could indicate that they are compliant and cooperative.

Whereas, if someone ignores an alert or does not follow the instructions, it could indicate that they are rebellious or suspicious. China did a similar thing in terms of contagion risk during the height of COVID-19.

While the UK government says data isn’t being collected and a response isn’t required to the alert in this scenario, it should be said that, over the last ten years, the UK government’s track record in terms of state surveillance has been far from exemplary.

State surveillance

More specifically, the UK government has a history of abusing its surveillance powers and violating people’s privacy rights, often without public knowledge or consent.

In a series of high-profile legal cases, the UK security services have been found to be in unlawful overreach of their data surveillance powers, with successive home secretaries failing to hold them to account.

It’s also been discovered that UK security services have shared data with foreign intelligence agencies, such as the US National Security Agency, without ensuring adequate protection of people’s privacy rights. With such a track record, it’s not surprising that there’s some scepticism when it comes to the government’s management of the emergency alerts system.

Fears around privacy are also understandable given concerns about how similar systems could operate further afield. If a government already monitors the mobile device of a journalist, activist or whistleblower, for example – a practice that is unfortunately not uncommon even in Europe – it’s possible they could then narrow down the location of that person by checking whether they receive alerts that are sent to a specific area.

Despite these issues, on balance, national alert systems are a useful tool for informing and protecting the public in case of emergencies. And instructing people to deactivate this function in their phones would not be responsible. At the same time, it’s a major oversimplification to claim there are no privacy risks whatsoever because the system does not collect personal information.

Indeed, privacy is not a luxury or a privilege. It is a fundamental human right that deserves respect and protection. This is why robust oversight of emergency alert systems is required to ensure they are not abused by governments.

![]()

Stergios Aidinlis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.