There was another of those moments when the world held its breath this week when news broke on March 14 of an incident between a US drone and two Russian jets. The unmanned US Reaper MQ-9 drone, reportedly on routine surveillance duties in international airspace, had to be brought down into the Black Sea after apparently being irretrievably damaged by the jets.

The US Department of Defense has just released footage of the incident, obtained, it appears, from the drone itself, which shows a Russian jet buzzing close to the unmanned Reaper drone and releasing quantities of what is reported to be fuel into its path. The video also reveals damage apparently caused by a collision between one of the jets and the drone.

The situation is still playing out. Both sides have claimed that the other was in the wrong. The Kremlin says that there was no contact between its jets and that the drone had crashed after making a “sharp manoeuvre”. The incident, which Russia said was due to increased US surveillance in the region, was a “provocation” which would draw an appropriate response if something of this nature happened again.

The US, meanwhile, accused the Russian pilots of “reckless, environmentally unsound and unprofessional manner” with the potential to escalate into a direct confrontation between the two sides.

Both sides are reportedly trying to salvage the wreckage of the drone, a huge intelligence boost for the Kremlin if it gets there first. Ashley S. Deeks, a former US state department lawyer, who now lectures in international law at the University of Virginia, writes here that she views the Russian assertions about the incident “with scepticism” and adds that the incident highlights “the right of countries to operate aircraft and drones in international airspace – even for the purposes of spying on another state”.

Read more:

Downing of US drone in Russian jet encounter prompts counterclaims of violations in the sky – an international law expert explores the arguments

We’ll bring you more analysis of this worrying episode as more details emerge.

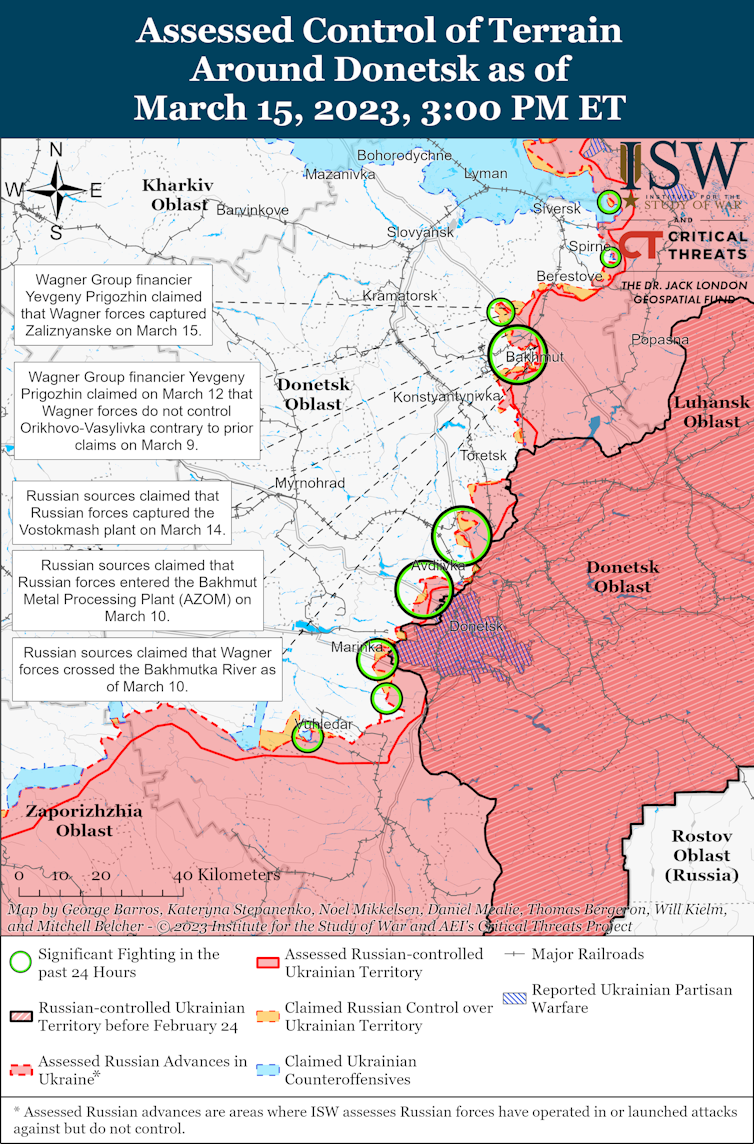

Meanwhile, on the ground, the two sides remain locked in a brutal battle for the town of Bakhmut in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. The brunt of the fighting on the Russian side has mainly been borne by the mercenaries of the Wagner Group and casualties on both sides are said to be high.

Chris Morris, an expert in military strategy from the University of Portsmouth, believes the cost to both sides in terms of causalities and military equipment far outweighs any strategic value that capturing the town – it’s a regional transport hub – may offer.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

Morris observes that the spring thaw – or rasputitsa – is hampering both sides as it makes the ground boggy and difficult to manoeuvre, especially for tanks and other armoured vehicles. But Russia has the added difficulty of supplying its war machine a long way from home.

Read more:

Ukraine war: a fight to the death in Bakhmut with both sides bogged in the spring thaw

Institute for the Study of War

And supplies of new equipment – or the lack of them – are increasingly becoming a problem for both sides. Notwithstanding its propaganda videos showing the ingenuity of Ukrainian engineers in repurposing or generally fixing up captured Russian equipment, Ukraine now largely depends on supplies from its Nato and European allies.

Matthew Powell, an expert in strategy and air power at the University of Portsmouth, says the problem of resupplying armies with equipment and ammunition is nothing new in war. But he notes that some of the weapons being used in Ukraine are expensive and sophisticated and take time to make. And then there’s the issue of training the Ukrainian military to use the latest Nato hardware, which can take months, even years.

What this may mean for commanders in the field, writes Powell, is that they become more risk averse. And the cost of this war is playing merry hell with defence budgets – not good news for economies struggling with a cost of living crisis.

Read more:

Ukraine war: high cost of replacing military hardware will change the nature of the conflict

An issue exercising legal minds over the past year has been the notion of “false flag” operations – hostile statements made or acts committed to pin the blame on another party, usually one’s enemy. This sort of trickery is so named because it is said to date back to the days, in the 16th century, when in naval battles a ship may fly the flag of their enemy to allow them to get close to a hostile warship before swapping colours back and opening fire.

False flag ops, which are a particular part of the Kremlin’s playbook, are not illegal under the rules of war, writes David Turns, a senior lecturer in international law at Cranfield University. But they are hedged about by caveats. At the Nuremberg war crimes trials, for example, a German officer was found to be guilty of a war crime after he fired on enemy troops from a vehicle marked with the Red Cross insignia. But another German officer, who dressed his men in US uniforms during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944 was found not guilty because they changed back into their own uniforms before actually fighting. Turns explains the legal niceties here.

Read more:

Ukraine war: ‘false flag’ operations – long used as weapons of mass distraction under the rules of conflict

Regional headaches

There were protests in Georgia last week after the government introduced a “foreign agents” law which many believed would have a negative effect on freedom of speech in the country. Similar to legislation passed last year in Russia, the law would make it pretty much impossible for Georgia to join the European Union, something it has long wanted to do and a step that appeared much closer after the EU granted the country candidate member status in June 2022.

The problem in Georgia is that the government’s relations with Moscow are at odds with the people. Natasha Lindstaedt, from the University of Essex, who specialises in authoritarian countries and democratic backsliding, was in Georgia in December and found that the vast majority of people she talked with wanted closer relations with the west. The ruling Georgia Dream party, meanwhile, is run by Bidzina Ivanishvili, a businessman who is understood to retain significant business assets in Russia and is more inclined to look to Moscow.

As Lindstaedt writes here, the government backed down – but Moscow’s man still holds the reins of power in Tbilisi, so Putin’s influence is still pervasive in Georgia.

Read more:

Georgia: ‘foreign agent law’ protests show disconnect between pro-Moscow government and west-leaning population

Moldova, meanwhile, is not a neighbour of Russia’s, but Moscow controls a small sliver of territory in the country’s north-east in the breakaway region of Transnistria and there is a mounting concern at the prospect that Vladimir Putin might use the Russian military presence there to create a second front against Ukraine.

Peter Hermes Furian via Shutterstock

We’ve already seen some Russian “false flags” being hoisted there in the shape of accusations that Ukraine and Moldova have been plotting to invade Transnistria. There was also talk of plans to use a “dirty bomb” there. As Stefan Wolff – an expert in international security at the University of Birmingham – points out, the possibility of a second front from Transnistria has meant that Kyiv has been forced to station troops in the region, just in case. “If nothing else,” he writes, “there is a danger of inadvertent escalation that could quickly engulf Transnistria and Moldova and draw in Ukraine and neighbouring Romania – a Nato member and a key ally of Sandu’s government, with deep historical ties to Moldova.”

Read more:

Ukraine war: Moldova could be the first domino in a new Russian plan for horizontal escalation

Lessons from history

It seems like ancient history, but nine years ago this week a referendum was held in Crimea to ask the people if they wanted to become part of Russia. Given the presence of Russian troops in the peninsula, it’s hardly surprising that the result was a resounding, but barely credible, “yes” vote of 96%.

Stephen Hall, who researches post-Soviet politics at the University of Bath, believes this was a massive missed opportunity for the west. Granted, there were sanctions, but they were nothing like as harsh as those imposed since last February. Hall believes this lacklustre response and the failure to act on any of the other “red lines” crossed by Putin over the past few years, will have convinced the Russian leader that the risks involved in the invasion were manageable.

Read more:

Ukraine war: how the west’s weak reaction to Crimea’s referendum paved the way for a wider invasion

If that seems like ancient history, then the recent anniversary of the revelation, 90 years ago, by a young Welsh journalist of Russia’s genocide in Ukraine – known as the Holodomor – are positively prehistoric. But we should remember Gareth Jones, who risked his life to bring the world the news that Stalin’s Russia was deliberately starving the Ukrainian people and was ridiculed by the disgracefully partisan international press for his pains. As Richard Sambrook, a professor of journalism at Cardiff University and a former head of BBC newsgathering, recounts, they certainly haven’t forgotten in Ukraine.

Read more:

Reporting Ukraine 90 years ago: the Welsh journalist who helped uncover Stalin’s genocide

And finally, while we’re at it, this week marked 70 years since Josef Stalin died. James Ryan, who teaches modern Russian history at Cardiff University, compares the great tyrant with the current occupant of the Kremlin.

Read more:

After 70 years, Stalin’s shadow still looms over Russia and Ukraine – but Putin is a tyrant in his own right

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

![]()