Having the capability to launch satellites from UK soil has been a long time coming. The recent attempted launch from Cornwall did not succeed, despite high hopes.

Nevertheless, it marks an ambitious new chapter in the UK’s long record of space exploration. As a country, we are good at making satellites, but we have typically sent them overseas to be launched.

While this approach can work very well, there are limitations – and circumstances can quickly change. It was previously common for UK and European satellites to be launched on Russian rockets. The Ukraine war means this route is no longer available.

Launches from UK soil will enhance a space sector that is already worth more than £16 billion per year to the economy. They might also help avoid the need to transport UK satellites long distances, along with the associated challenges of ensuring the security of technology contained within them.

During Virgin Orbit’s mission on Monday January 9, a rocket with satellites was carried up under the wing of an aircraft, which took off from the UK’s newly operational spaceport in Cornwall.

The plane flew towards the southwest coast of Ireland, where the rocket was launched from the wing and continued upwards towards space. While the rocket’s first stage (or section) operated as expected, the second stage burnt up as it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere, causing the loss of all nine satellites. Two of these, commissioned by the UK Ministry of Defence, carried space weather and radiation monitors designed here at the University of Surrey’s Space Centre. We were really looking forward to seeing the data from the instruments, but it was not to be.

The launch is still typically the riskiest part of any mission. For a mature rocket system, the launch failure rate is usually just a few percent. For a relatively new rocket system, the failure rate is typically much higher. Such a failure cannot be considered as being particularly unusual at this stage in the development of Virgin Orbit’s rocket.

Extra pressure

Flight data transmitted by the rocket will be studied and analysed very carefully, and the source of the problem will almost certainly be found and fixed. Teams involved will learn from the experience, re-group and try again. Such efforts make spaceflight safer and more reliable.

While the cause of the failure is still being investigated and a further launch attempt is expected, the unsuccessful outcome creates extra pressure on Virgin Orbit. However, what’s needed is not just a one-off success but long-term reliability.

Nasa, Author provided

An early mistake

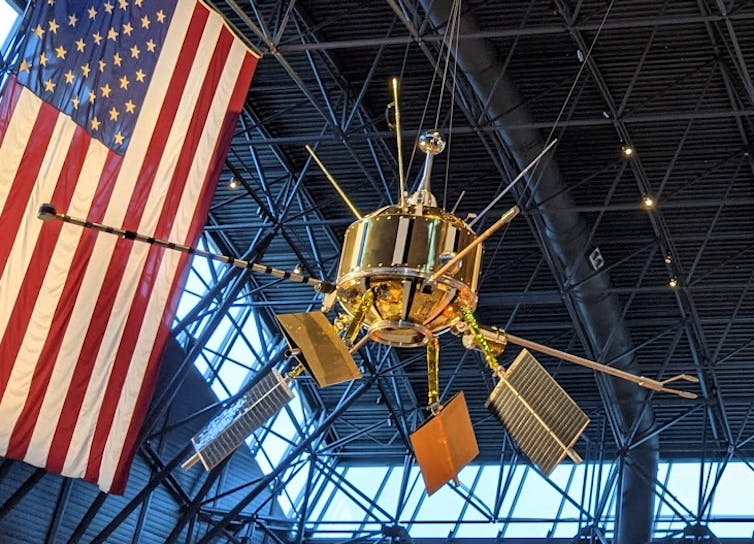

The fact that the UK is working to launch space missions from its own soil marks a remarkable turnaround. The UK launched its first satellite, Ariel-1, on a US rocket back in 1962.

Unfortunately, just two months after launch, the US military carried out the huge “Starfish Prime” nuclear test high up in the atmosphere. Radiation from the test killed off Ariel-1, along with other satellites. But this turned out to be a minor setback, since Ariel-1 kicked-off the successful UK satellite industry we know today.

Realising the benefits of sovereign launch capacity, the UK developed its own rocket, Black Arrow, which blasted-off flawlessly from Australia in 1971. However, the government of the day cancelled further production of this type of rocket just after launch because it was deemed too expensive.

Launch leadership in western Europe was then handed to France, which subsequently developed the successful Ariane rocket system. Indeed, until very recently, UK space policy could be summarised as “satellites but no launchers”.

While using foreign and commercial rockets is often perfectly acceptable, it means joining a queue of commercial and national customers. These launches can be delayed or, in the worst cases, blocked.

ESA, Author provided

In future, we could have a stockpile of key UK satellites built and ready to launch, in the knowledge that they can get to space as soon as needed. A new launch capability also boosts the UK space ecosystem and eliminates the need for the long-distance shipment of complex and sensitive equipment to other countries, which is costly and may present security challenges.

Rockets launched from under the wing of an aircraft, like Virgin Orbit’s, fall into a category known as a “horizontal” launch. These were pioneered by an American air-launched rocket system called Pegasus, which first flew in 1990.

This way of launching saves fuel, because the rocket is carried the first 10km upwards by the aircraft. By varying the location and direction of the aircraft at the time of launch, controllers can directly place satellites into a variety of different orbital paths around the Earth. This gives a degree of flexibility not possible with fixed launch sites on the ground.

Shutterstock

One downside of horizontal launches is that the payload capacity – how much mass the rocket can carry into space – is limited.

In addition to the new UK launch base in Cornwall, other spaceports in Snowdonia, Prestwick and Campbeltown will carry out horizontal launches once they are operational. These will compete with UK spaceports designed for vertical launches, where the rocket travels upwards off the ground. Sites with this capability are planned for Sutherland, the Western Isles and Shetland.

Once up and running, UK-based rockets will cater to a growing local market, since their payload capacities will be well-matched to the “smallsats” (satellites with masses up to a few hundred kg) with which the UK has a strong track record.

The first Spaceport Cornwall launch did not reach orbit. But the UK space industry has bounced back from setbacks before and can do so again. This gives us the confidence to look beyond this bump in the road and towards the next exciting chapter in the story.

![]()

Keith Ryden is the Director of Surrey Space Centre, which designed instruments carried on the LauncherOne rocket. He has been funded by the UK Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) and the European Space Agency (Esa) to undertake work on space radiation and space weather instruments.

Prof Craig Underwood is Emeritus Professor of Spacecraft Engineering at the University of Surrey. The radiation monitor flown on LauncherOne was based on an instrument which he designed, and which was first flown on the UK’s TechDemoSat-1 (Technology Demonstration Satellite-1) mission in 2014. He has received past funding from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the UK Space Agency.