As an expert in media and cultural studies, I once appeared in a television series about technology in the home during the last three decades of the 20th century.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here.

I wanted to suggest that the UK in the 1970s should be remembered as a decade of relative social equality and contentment, where wage inequality was at its lowest (as the New Earnings Survey shows us).

But I couldn’t make this argument because the production company had already bought the media rights for showing news footage from the so-called “winter of discontent” (1978-79). It showed rubbish piled high on London streets due to a public service workers’ strike.

“Everyone knows that the 1970s was awful,” the producer seemed to be saying, “so that’s what we’re going to run with.”

Yet if anyone is looking for discontent, the best place to find it would be in periods when the gap between the richest and the poorest is at its most extreme.

Income inequality is not only linked to feelings of unhappiness and discontentment, it is also detrimental to national health. Wage inequality actually increased massively in the 1980s and in the decades that followed.

The winter of discontent wasn’t an assessment made by historians looking back to the end of the 1970s. It was a phrase deployed by newspapers who sought to vilify union power and the sort of progressive taxation that put a cap on wage inequality.

History was being forged not just on picket lines but in newspaper editorials and TV newsrooms. The 1970s have suffered in popular memory ever since.

A question of taste

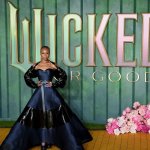

The same could be said about our memory of 1970s tastes. Nostalgic TV programmes often want us to remember the ’70s as the decade that “taste forgot”. They offer up montages of space hoppers, avocado-coloured bathroom suites, lava lamps, garish wallpaper and flared corduroy trousers.

Shutterstock

Director Mike Leigh’s 1977 TV play Abigail’s Party is a perfect example of how certain tastes were denigrated at the time.

The two central characters, Beverly and Laurence Moss, have become infamous grotesques for a form of status-striving bad taste. The playwright Denis Potter described the play as “a prolonged jeer, twitching with genuine hatred, about the dreadful suburban tastes of the dreadful lower-middle classes”.

The play is condescending about Beverly’s appreciation of the singer Demis Roussos and Stephen Pearson’s painting Wings of Love. But it reserves its real sneer for Laurence’s Van Gogh poster and his leather-bound, unread books.

The play shows us a couple who live in a modern home with a desirable open-plan layout, struggling to come to terms with having white-collar professions – Laurence is that much-derided figure, an estate agent – with low salaries and an even lower sense of prestige.

A class system in flux

In the 1960s and early ’70s, work and class were changing. Sociologists like Michael Young tried out new terms for thinking about class.

He wrote of the “technician class” and the “administrative class” to try and capture a new state of affairs. One where someone working at Ford might earn as much as a schoolteacher. Where once high-esteem jobs were no longer seen as impressive. And where a whole new set of industries and occupations, such as social workers and computer operators, were emerging.

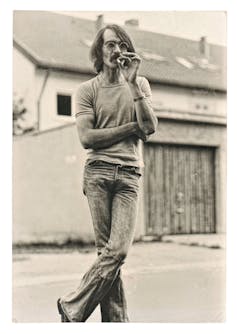

The late 1960s and 1970s marked a period where new tastes were introduced into the British home. They marked a desire to escape the 19th-century British class system and embrace a new world of pleasure and ease.

One way of escaping the rigidity of Britain’s class structure was to look abroad. The social democracies of Scandinavian countries provided an example. By the end of the 1980s, Swedish-Dutch home furnishing brand Ikea would provide many homes with a sort of loose Scandinavian lifestyle, but before that Britain had shops like Habitat.

In the mid-’70s, Habitat had a similar mass appeal as Ikea has now, and catered for the student bedsit as much as the designer-conscious shopper with deep pockets. Its popularity was not just a sign of changing tastes but of changing attitudes towards, and experiences of, class.

Shutterstock

The democratic promise that came with flat-pack furniture and exotic items such as duvets coincided with a period of relative income equality. It produced a new cross-class culture that is still enjoyed today, even if it conflicts with a wider sense of class disparity. Who doesn’t now sleep under a duvet, or own something from Ikea?

The new tastes emerging in the 1960s and ’70s offered Britons a less uptight way of living – one less encumbered by an older sense of Britishness and the class tastes that went with it.

But to properly reassess the tastes of the 1970s, we also need to consign those images of the “winter of discontent” to the dustbin of history.

![]()

Ben Highmore receives funding from the Leverhulme Trust.