Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the populist radical right party Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), may have emerged as the victor in Italy’s recent elections, but she did so at the head of a delicately balanced coalition of parties – one that included Matteo Salvini, the man once spoken of in the same terms as Meloni herself.

Before Brothers of Italy’s meteoric rise, it was Salvini who was seen as the populist right-wing threat in Italy. Now he finds himself playing second fiddle to Meloni.

Salvini’s League (Lega) teamed up with Brothers of Italy in a pre-election alliance that came with the promise of being part of a government led by the radical right. But the deal came at a cost. The relationship between the two allies has evolved into a zero-sum game, with Brothers of Italy taking electoral support from the League.

Brothers of Italy won 26% of the national vote in the September election — a share that dwarfs the results of its two coalition partners combined. Salvini’s League took 8.8% and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia (the third partner in the alliance) took 8.1%.

This was a stunning reversal of fortunes given that in the previous election in 2018, Brothers of Italy won just 4.4% of the vote. That year the League took 17.4% and Forza Italia 14%.

Decimated in the north

A pressing concern for Salvini is the extent to which Brothers of Italy has eaten into the League’s historical strongholds in the north of Italy. The League was once called the Northern League, precisely because it sought to represent these areas specifically. It was established in 1991 by uniting several regional parties and movements and for most of its history its key goal was regional autonomy for the north of Italy. It is only in the past ten years that the party has tried to expand into the south. Along with this expansion came a pivot towards nationalist campaign tactics and more radical anti-immigration rhetoric.

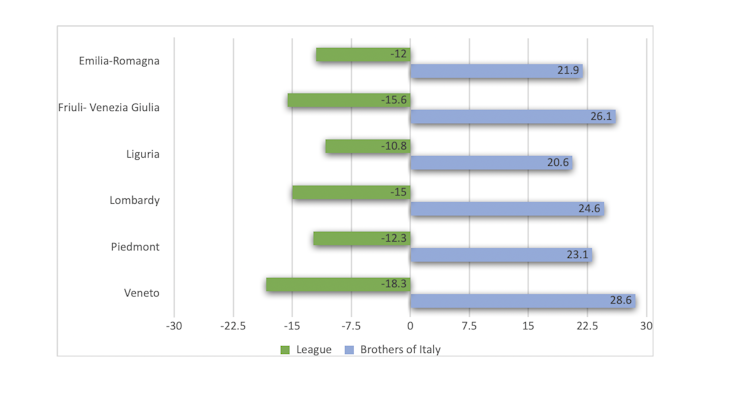

Despite this history as a northern party, Brothers of Italy has overtaken the League in the whole of the north – and by a large margin.

Election results in the Northern regions

Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, Author provided

In Lombardy, support for the League dropped by 15 percentage points between the 2018 and 2022 elections. In Veneto, it fell by 18.3 percentage points.

For voters, the two parties are now virtually indistinguishable in terms of ideology and policy, which has made it easier for the former to cannibalise the other. The League – and Salvini – are confronting an existential threat.

Percentage-point losses and gains between the 2018 and 2022 elections

Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, Author provided

We can’t all be outsiders

There is an important lesson here for populist radical-right parties more generally. By dropping regionalism and trying to “go national” Salvini has implicitly invited the (large) constituency of right-wing voters who embrace radical ideas about migration and law and order to choose between his party and Meloni’s on the basis of credibility, since there is no longer anything to distinguish them in terms of ideology. In this comparison, the League is on the back foot, having taken part in multiple governments in recent years and, at many points, compromising with other parties. Brothers of Italy can therefore assume the role of disruptive outsider and appeal to voters who are discontent with the status quo.

Apparently recognising Salvini’s weakness in this respect, Brothers of Italy’s election campaign framed Meloni as the only untested alternative on offer – the only candidate of the right untainted by compromise with the left.

Their wrangling is a case study in a new phase for Europe’s radical right. These parties are largely thought of as the “challengers” to the traditional mainstream but their electoral successes have pushed them into government. Now, they compete not just against the traditional establishment but also among themselves for the control of the executive.

This is the first time that a western European country is likely to be run by a populist radical-right party that also needs to share government with another populist radical-right competitor. Given that multiple similar parties operate elsewhere, too, similar scenarios potentially lie ahead in countries such as Denmark, France and the Netherlands.

Tensions of this kind create a very interesting dynamic for government. Meloni needs Salvini as a junior partner in her coalition but it is inevitable that the arrangement will be beset by infighting. Indeed, Salvini’s political future practically depends on his ability to make it so. It is logical to expect that Salvini will try to fight back against Meloni’s new dominance by keeping one foot in and one foot out of government. He will seek to hold positions of power but will agitate from within. We might expect him, for example, to loudly criticise the government for not cutting taxes sufficiently (a key theme for League voters), being too worried about the country’s deficit, or too subservient to the “diktats” of the European Commission.

We might even expect him to fight future campaigns on the idea that he was unwilling to compromise in this government. It’s a new iteration of a familiar problem – what happens to parties that wish to be seen as outsiders once they are included in coalition governments? Only this time, all the outsiders are on the inside.

![]()

Daniele Albertazzi has received funding from AHRC, British Academy, ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust.

Mattia Zulianello has received funding from the ESRC.