If you’re planning a wedding in England or Wales, there’s a good chance you’re facing something of a legal conundrum. Whether it’s that you’d always wanted to get married on a beach or are piecing together an interfaith ceremony, many betrothal options that you might think are fairly standard are actually out of sync with current weddings legislation.

In July 2022, the Law Commission published proposals for a new weddings law. The fact that the report opens with a seven-page glossary of terms is a good indication of quite how complex – and how pressing – an area of legal reform this is.

Much of the current law dates back to the Georgian era and some of it, all the way back to the Clandestine Marriages Act of 1753. Such ancient and therefore culturally specific legislation stands in stark contrast to the cross-cultural influences writ large across the globalised world in which we live.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Five dating tips from the Georgian era

Baby names: why we all choose the same ones

Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends – how we’ve become tougher on adultery

As my research shows, couples often borrow rituals, prioritise rites and personalise ceremonies for weddings that are not, in fact, recognised by the law at all. Many people see the current law as obstructive to getting married in a way that is meaningful to them.

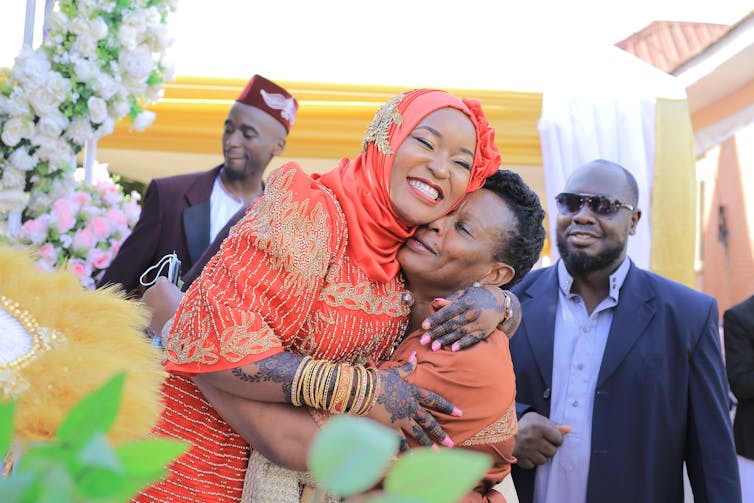

Amir Mukhtar | Shutterstock

Why couples often have two ceremonies

Between 2020 and 2021, we interviewed 83 individuals and couples to investigate non-legally binding weddings in England and Wales. These included Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, pagan, interfaith and humanist weddings, as well as weddings led by an independent celebrants.

Most of our interviewees had had to have a dual ceremony in order for their marriage to be legal. And the legally recognised ceremony was often not the one they considered to be their “real” wedding.

These non-legally binding ceremonies were both religious and non-religious. Many of our participants viewed the law as obstructive to getting married in a way they found meaningful.

COVID has further impacted people’s choices. Our study found that many more non-legally binding ceremonies occurred during lockdown.

Svetype26 | Shutterstock

What current wedding legislation requires

There are multiple ways in which a couple can legally marry under the current law. For all ceremonies, preliminaries (the giving of notice, the publication of banns or the issuing of licences) have to be conducted.

Legally recognised locations include Anglican churches, registered places of worship, register offices and approved premises. Jewish and Quaker weddings can take place anywhere.

And who must oversee the ceremony varies similarly, from an ordained member of the Anglican clergy, a superintendent registrar, a registrar to an authorised person. Jewish and Quaker weddings can be led by anyone suitable.

Weddings in other faiths, including Muslim nikah weddings, are legally recognised when conducted in certified places of worship which are registered for weddings. The requisite formalities here include giving notice and being conducted by an authorised person or registrar.

Civil ceremonies have to take place in a register office or an approved premises and in the presence of a superintendent registrar and registrar.

All ceremonies have to include declarations of consent and terms of contract. These prescribed words include not knowing of “any lawful impediment why” the couple may not marry, and calling on the “persons here present to witness” the wedding. They stem either from the approved forms of service for Anglican weddings or, for civil weddings and those in registered placed of worship, are modelled on the Anglican service. Jewish and Quaker traditions specify their own usages.

kabunga Godfrey | Shutterstock

How people really want to get married

We found that couples would prefer to consent to marry in a way which accords with their own beliefs and wishes, rather than be compelled to use the prescribed words.

Of course, these could continue to be used by those with whom they resonate. Removing the prescription would simply enable others to use words that hold meaning for them.

Some interviewees found venue restrictions to be problematic. Outdoor weddings remain limited, even with recent reforms which have allowed weddings to occur outdoors on the grounds of an approved premises. Being outdoors, for example, is particularly significant for pagan weddings. Being able to choose where would also help keep costs lower.

Rawpixel.com | Shutterstock

Reforms in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Ireland, Jersey and Guernsey have all essentially recognised that people no longer live, marry and die in the same communities and that the law must evolve accordingly.

In the Law Commission’s radical but realistic proposals, the key idea is that the system of regulation moves from focusing on where the wedding occurs (the building) to who oversees the ceremony. The report recommends that an officiant be present at every ceremony, regardless of the shape it might take. If implemented, this would indeed provide a universal rule for all.

The process of marrying has to both provide certainty in legal terms, as to the contract that marriage is, and be flexible in recognition of the modern, plural society in which we live.

![]()

Rajnaara C Akhtar receives funding from the Nuffield Foundation.