In the fairy-tale landscape of the Isle of Skye off the north-west coast of Scotland, the skull of one of the most ancient salamanders ever discovered to date was excavated from Jurassic limestones. But it would be decades until scientists had the technology and the funding to piece the salamander together.

Part of the skeleton was collected in the early 1970s when palaeontologists Michael Waldman and Robert Savage noticed black bone exposed on the hard grey rock surface, hinting at a fossil locked inside. They collected it realising that it could be something important. Although parts of the fossil were subsequently exposed, it was too little to warrant a detailed study. Therefore, the fossil remained in the rock and unstudied for another 45 years.

Field trips to the site started again in 2004 and several fossils were found, including salamanders. Roger Benson examined the block collected in the 1970s. He realised that the broken surface matched a specimen that he’d collected in 2016.

Most bones collected on field trips don’t get studied immediately. Getting money for fieldwork is difficult but it’s even harder to secure funding to study the fossils you collect. It’s not uncommon for them to be left unstudied for decades.

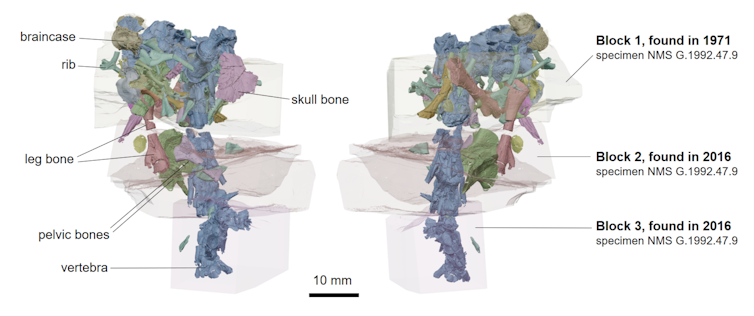

X-ray microCT scanning revealed the rock held the remains of a new fossil species of salamander: Mamorerpeton wakei. At 166 million years old, it is one of the oldest-known salamanders and it documents one of the earliest known stages of their evolution.

Salamander fossils are rare. For the whole of the Jurassic period (201-145 million years ago) fewer than 20 species have been found. By contrast, we know of more than 450 dinosaur species. Salamanders are harder to find because they are small and delicate – but this lack of knowledge might also be due to lack of scientific attention.

Recognition at last

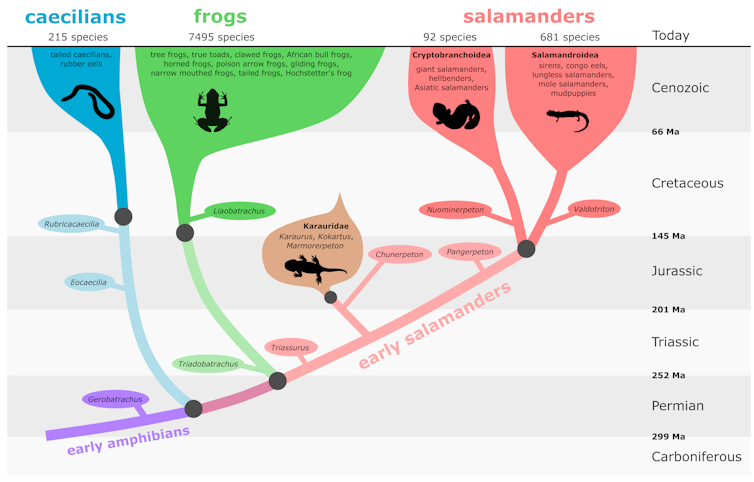

Palaeontologists had the first hints of evidence of an extinct salamander species 30 years ago when parts of fossilised backbone and jaw bones were found near Oxford in England. However, it was largely ignored by the scientific community in favour of research into the Karaurus salamander from Kazakhstan in the Middle Jurassic period. Until now, the Karaurus was often treated as the common ancestor of modern salamanders.

The Mamorerpeton fossil bones are still preserved inside hard rock. Until we used X-ray microCT scanning we weren’t sure of the contents. Most blocks were collected without knowing exactly what was inside them. A fossil block recovered in 2016 was found to be the other half of a specimen collected more than 40 years earlier from the same place.

Elizabeth Griffiths, Lucy Hill, Roger Benson, Marc Jones.

Most of the skeleton was preserved, including the skull and tail. Turning bones into digital models is painstaking work, but it allowed us to make an (uncrushed) three-dimensional model of the skull, which is unprecedented for a fossil salamander.

Often, fossils are collected on field trips but not studied for many years for lack of time or expertise. For the 1971 specimen, the edges of some bones were visible but removing the bones would have been very difficult. Mechanical removal could have damaged them, but X-ray microCT scanning allowed us to see the bones clearly.

What we learnt

Our new analysis puts the new species Marmorerpeton inside the extinct group Karauridae. Members of this group all have skull bones with a crocodile-like ornament and have bony projections behind the eye. The new species is named after the late Professor David Wake, a leading American authority on salamander evolution.

The wide skull, deep tail, and limb bones with unfinished ends indicate Marmorerpeton had an aquatic lifestyle similar to the living hellbender salamander of North America (Cryptobranchus) and the giant salamander of China and Japan (Andrias). They probably fed on insects using suction feeding, and laid eggs that were fertilised externally.

Salamanders are generally either, aquatic, (such as Siren), land-based (such as Plethodon) or begin as aquatic and become land-based in adulthood (such as Triturus). It is possible that the earliest salamanders were all aquatic but not enough fossils have been found to be sure.

Our study shakes up what scientists thought they knew about salamander evolution. Our analysis suggests several fossils from the Jurassic and Cretaceous of China (such as Chunerpeton), once thought to be early members of modern salamander groups, are not closely related to living salamanders. Previous studies relied too heavily on Karaurus (the Archaeopteryx of salamanders), from the Late Jurassic of Kazakhstan.

Silhouettes are from Phylopic.org and orginals by Marc Jones.

Salamanders today

Salamanders are crucial to science. Scientists have studied salamanders for clues to understand skeletal development, limb and organ regeneration, and toxicology in all vertebrates, but people know surprisingly little about salamanders themselves. Many people think salamanders are a type of lizard and are unaware of how diverse they are.

There are more than [750 species alive today] spread across northern continents. There are eel-like forms living in flooded <a href=

caves, swimming beaked herbivores, and small land-based salamanders which climb trees using their tails or use chameleon-like tongues to catch prey. Several species show parental care such as nest preparation and nest guarding.

The UK has three species of salamander. All of them live in the water as juveniles (newts) and are land-based as adults. They return to the water to breed. Salamanders are important to food webs. Many of them eat lots of insects and they are prey for many animals and even some plants. Unfortunately many species are threatened by habitat loss.

The Middle Jurassic fossil localities of Skye are globally important. Fossils of lizard-like reptiles, early lizards, crocodylomorphs, turtles, pterosaurs, mammaliaforms, and long-necked dinosaurs have all been found there.

![]()

Marc Emyr Huw Jones receives funding from The Leverhulme trust and previously from The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council UK, Australian Research Council, Palaeontological Association, and Synthesys. He is a Fellow of the Linnean Society, member of the Anatomical Society, and member of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Roger Benson currently receives funding the Leverhulme Trust and Natural Environments Research Council, and has previously received funding from the European Research Council, Palaeontological Association and St Edmund Hall at the University of Oxford.

Susan Evans currently receives funding from the Leverhulme Trust and the Human Frontiers of Science Programme, and has previously been funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Palaeontological Society, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. She is a member of the Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology, the Anatomical Society, the Palaeontographical Society, and the Palaeontological Association, and is a Fellow of the Linnean Society and the Zoological Society.