This summer sees our love for dinosaurs manifest in two major releases: the David Attenborough documentary Prehistoric Planet, and Jurassic World: Dominion. Such multi-million dollar projects are a far cry from the first attempts to bring dinosaurs to life in people’s imagination.

Perhaps the most famous of these took place almost 170 years ago at Crystal Palace Park, in south-east London, where over 30 life-sized sculptures of prehistoric animals, including dinosaurs, revealed extinct life to the public for the first time.

Much like the unveiling of Jurassic Park’s computer generated dinosaurs in 1993, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs stunned visitors. This historic site still enjoys hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

Our new book, The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, reveals that neglect of the site allowed seven – almost a fifth – of the original sculptures to disappear. It was thought the original park had 32 sculptures, of which only 29 originals (with one replica, making 30) stand today. We showed 37 once existed.

The lost statues include the tapir-like Palaeotherium magnum, three delicate llama-like Anoplotherium gracile, two Jurassic pterodactyls, and a female giant deer. It’s unknown when and how each vanished, but dereliction, site redevelopment and perhaps vandalism may be responsible.

Built as part of the Crystal Palace Park project, the dinosaurs were unveiled in 1854 and completed in 1855. Although books and magazines brought dinosaurs to the attention of the rich and educated in the early 1800s, fossils were an interest reserved for the upper tiers of society. The sculptures, crafted by a team led by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, aimed to introduce prehistoric life to the wider public.

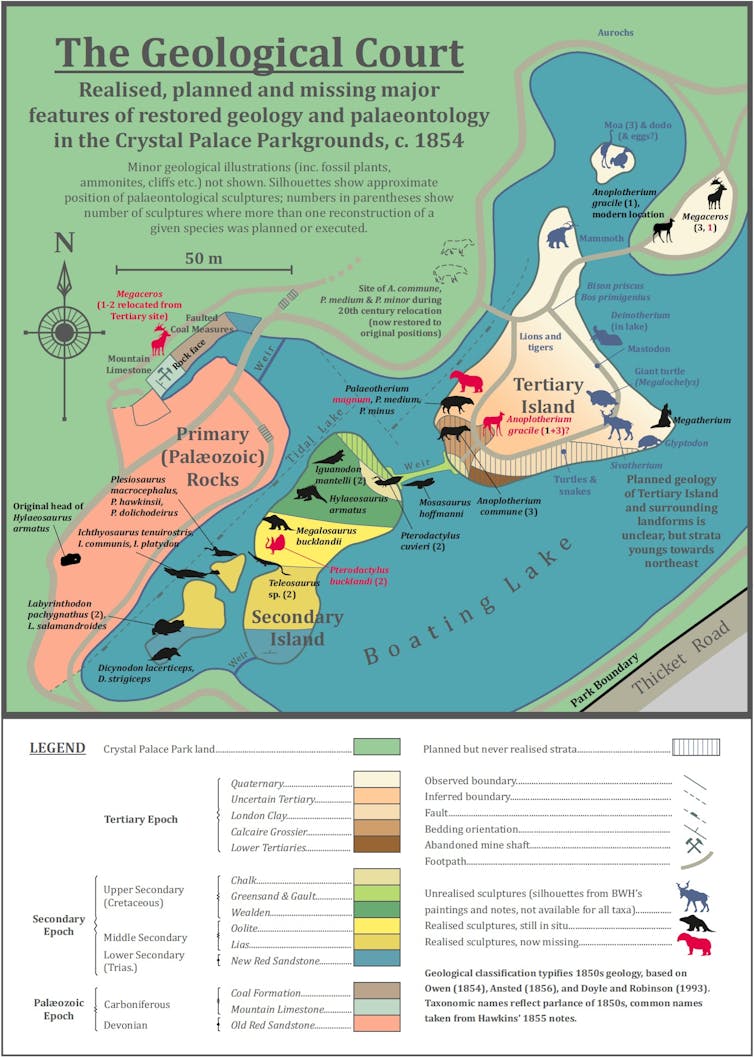

Image by Mark P. Witton and Ellinor Michel.

Working with geologists David Thomas Ansted and Joseph Campbell, Hawkins created a learning experience one part spectacle and one part enlightenment: the “Geological Court”. This showcase of geological and palaeontological science allowed visitors to walk through geological time.

The largest of Hawkins’ sculptures were the dinosaurs, reaching over 10m long. Mock geological features contained hundreds of tonnes of rocks sourced from all over the UK. This was expensive blockbuster edutainment.

For all the mockery cast on the sculptures for their scientific inaccuracy today, at the time they were cutting edge representations of extinct species – and a major hit with the public. But budget issues saw the site fall into disrepair from 1870 onward. Degraded and patchy records mean the full extent of the original display is uncertain.

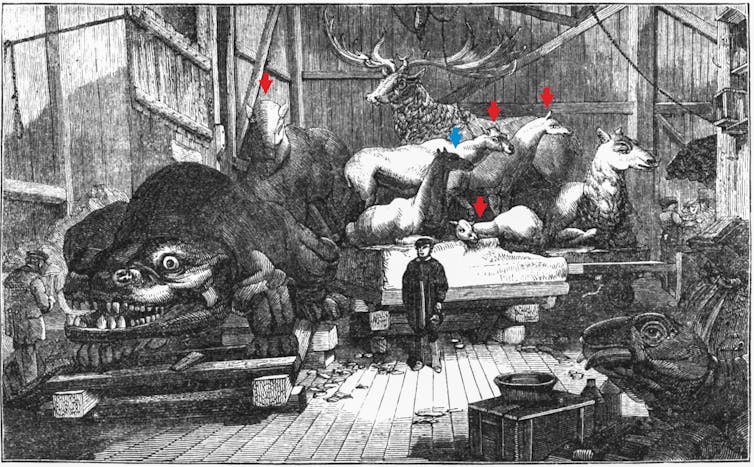

Image in public domain, modified by Mark P. Witton and Ellinor Michel.

Virtually no physical remains of the missing sculptures exist. Only archive photographs, illustrations and texts prove their existence. For example, the image above shows several models that no longer exist.

From these sources, we also re-identified one sculpture at the park – an alleged giant deer fawn – as Anoplotherium gracile, which resembles a gazelle and is the sole surviving representative of what was once a group of four statues.

If we know almost 20% of this unique Victorian site was allowed to vanish so quietly, what else might be missing?

A history at risk of extinction

While the Victorian artistry and creative engineering that went into creating the Geological Court is celebrated today, the site has long suffered from a lack of conservation.

The unchanging nature of the concrete displays, now numerous generations behind the latest palaeontological findings, gives a sense the they will always be here. But visit the site today and it’s obvious many of the displays are still crumbling.

Weathering, vandalism and redevelopment mean the Geological Court is a blend of originals and replicas of structures destroyed in the mid-20th century.

Photo by Mark P. Witton

There is hope. The Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs charity was established in 2013, and the entire site is now Grade 1 listed and on the official Heritage At Risk Register by Historic England.

But the Geological Court’s status is a precarious one. Without urgent conservation the sculptures face major deterioration.

As you enjoy the digital descendants of Hawkins’ dinosaurs when they hit our screens this summer, spare a thought for their Victorian ancestors. To lose what remains of these displays, that changed the way many people thought about life on Earth, would be tragic.

![]()

Mark P. Witton is the co-author of The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, out now on Crowood Press.

Ellinor Michel is the co-author of The Art and Science of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, out now on Crowood Press.