There has been an extraordinary transformation in how the media talk about culture change in the UK in just the last few years – and it’s starting to infect public opinion.

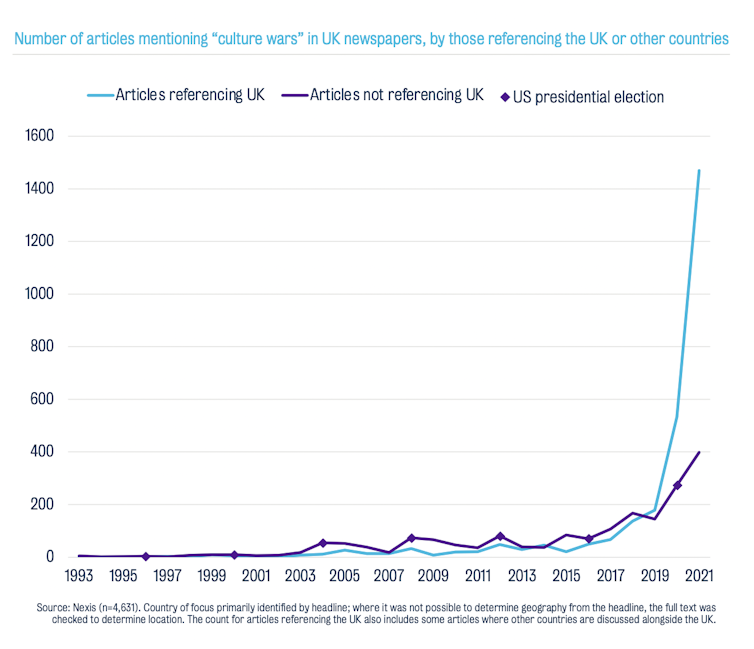

In 2015, there were only 21 articles in UK newspapers that talked about a UK “culture war”. Our new survey shows that by 2021 there were nearly 1,500.

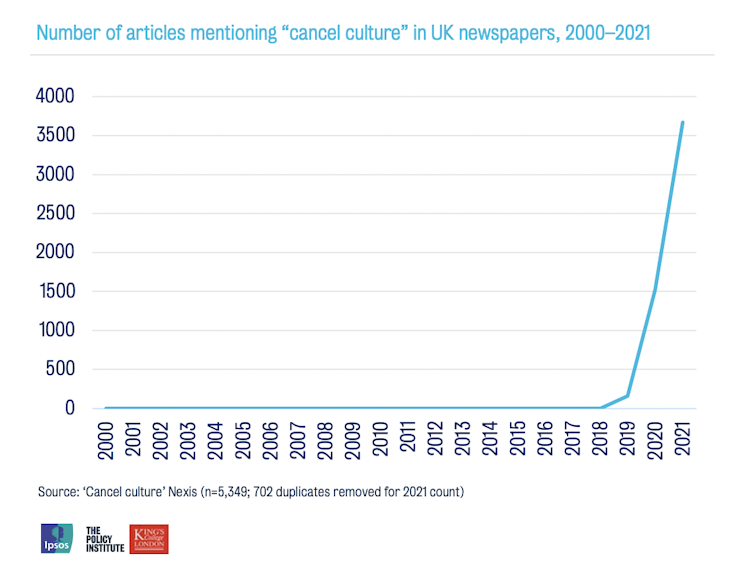

“Cancel culture” didn’t exist at all in the British mainstream media in 2017 – but in 2021 there were an astonishing 3,670 articles that used the term.

And the public is starting to notice. In 2020, 47% had never even heard of cancel culture, but this had halved by 2022. More generally, most people now agree that the UK is divided by culture wars, up from our last study in 2020. This increase cuts across demographics and political identities, but it’s older groups and Conservatives who have moved the most.

This shifting ground is also seen in how people view that other key term in the culture wars discussion – “woke”. In our 2020 study, the most common response when asking people whether “woke” was a compliment or an insult was “I don’t know what it means”, while those who did have a view were evenly split between thinking of it as a compliment and thinking of it as an insult.

KCL Policy Institute

But many more now know what it means – and people have shifted firmly towards seeing it as insulting. That’s not surprising when you see our analysis of the context in which “woke” is used, which is overwhelmingly derogatory – language such as “embittered”, “blinkered”, “puritan”, “ludicrous”, “insidious”, even “terrorist”, are all linked to the term.

This leaves us in a deeply worrying position.

Some say these debates don’t matter, or that they’re manufactured by the media and politicians rather than being an authentic concern among the public. It’s true that we don’t see culture war issues top people’s lists of the most important issues facing the country – the cost of living crisis, strains on the NHS, war in Europe and the pandemic are all viewed as bigger priorities. As shadow foreign secretary David Lammy said, this culture change debate doesn’t come up “on the doorstep”.

Front page to front bench

But this misreads the importance of the culture war story. Who controls the cultural narrative of a country matters because it sets the tone for politics more generally. And, as research by the thinktank UK in a Changing Europe shows, the cultural instincts of Conservative MPs are much closer to the average voter than Labour MPs. There is a clear incentive, therefore, for the current party of government to maintain a focus on these issues.

When talk of a culture war first emerged in the US in the 1990s, it was described as a “war for the soul of America”. It can become powerful stuff, not due to the great national importance of the individual issues pulled in, but because that process creates tribes, as more and more cultural issues become rolled into your political identity.

Yet the UK is not the US. The country has very different historic, cultural and political contexts, so it’s not inevitable that the same scenarios will unfold. But, on the other hand, complacency could lead the UK down a path to an equally bad place. Analysis of political manifestos across 21 countries, including the UK, over past 50 years shows a long trend towards a greater focus on cultural over economic issues in what the parties promise. In the UK, this has been sharpened by Brexit, which was, at its core, about different views of the country and its values.

KCL Policy Institute

One of the defining features of the culture wars is deep suspicion of the motives of the “other side”. One group believes they are engaged in a legitimate battle against cultural institutions captured by a view of the world that doesn’t reflect the values of ordinary people. The other sees this purely as a cynical political tactic.

Debating which of these is true misses the point. What matters more is the sense of conflict the tone of the debate creates, which sets identities into warring tribes and means compromise becomes impossible. Our culture and values, and how they’re changing, are completely legitimate, in fact, essential aspects of political discussion – but how we do it is important. The speed and scale of the adoption of culture war rhetoric in the UK is a dangerous game.

![]()

Bobby Duffy receives funding from Unbound Philanthropy, the ESRC, the Britsh Academy and the European Commission's H2020 programme.