Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock

Many wondered whether the COVID lockdowns would lead to a baby boom or a bust. We finally have some answers – for the UK, at least.

Broadly, provisional data from the Office for National Statistics suggests there was a temporary decline in babies conceived during the first three months of the first lockdown in 2020, but then the fertility rate rebounded to levels above those seen in previous years. Let’s take a closer look.

Read more:

COVID-19 pandemic may produce dramatic changes in life expectancy, birth rates and immigration

The earliest we would have expected COVID to affect people’s decisions to become pregnant would have been February 2020, influencing births on average from November 2020.

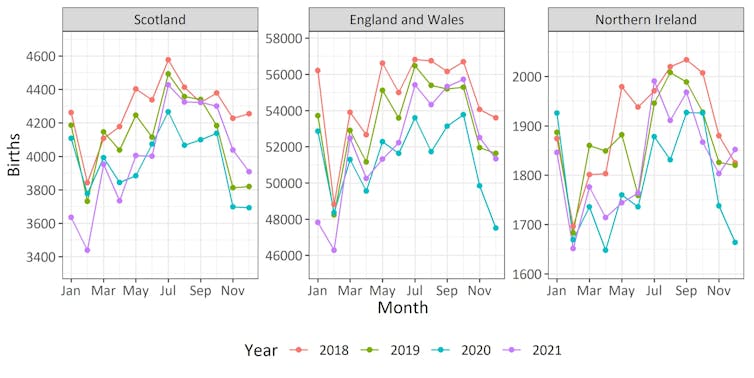

In the graph below, the number of monthly births are plotted for the years 2018-21 in Scotland, England and Wales, and Northern Ireland. You can see that before the pandemic, the number of births had been falling in all countries of the UK.

By 2019, the average fertility rate for Scotland was 1.37 births per woman. This was the lowest level ever recorded and was significantly lower than the level in 2008 (around 1.77) before the effects of the economic recession hit.

In 2019, fertility rates were slightly higher in England and Wales (1.65) and Northern Ireland (1.82) than in Scotland, but again, these levels were some of the lowest ever recorded.

The onset of the pandemic was initially associated with a decline in the number of births, particularly from November 2020 to February 2021. Yet from March 2021 onward, the number of monthly births recovered and sometimes exceeded 2019 levels, particularly in the last quarter of 2021. This is despite there having been a second wave of the pandemic in the UK in late 2020 and early 2021.

For England and Wales, the average fertility rate in 2021 was 1.61 children per woman compared with 1.58 in 2020 – the first time since 2012 this figure has increased from one year to the next.

This recovery might be explained by births taking place where conception had been postponed during the first lockdown. Or perhaps birth rates had reached their lowest point and would have increased, anyway.

Total number of births by month, 2018-21

NRS (2022); ONS (2022); NISRA (2022), Author provided

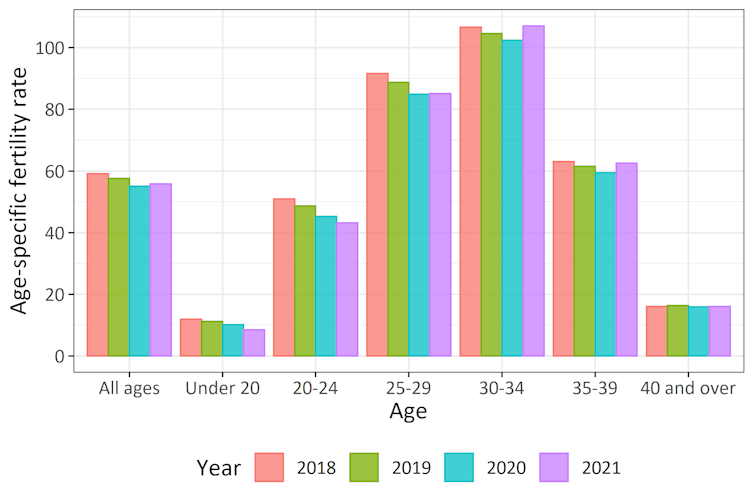

We can find out more about what’s happened if we look at trends in birth rates by mother’s age. These age-specific fertility rates are, at the time of writing, only published up to 2021 for England and Wales, and are only available for women.

This data shows that the effect of the pandemic on childbearing in England and Wales differed by age. Among women aged under 25, fertility rates fell and continued to fall through 2020 and 2021. Among women in their 30s, fertility rates recovered in 2021 after falling in 2020. Rates for those in their early 40s have remained stable at a low level.

Fertility rates by age of mother, England and Wales, 2018-21

ONS (2022), Author provided

So, what might be happening? In a research article written in 2021, we speculated that the pandemic would not have a uniform effect on fertility rates, but would affect childbearing differently based on a woman’s age.

We considered several ways the pandemic might decrease fertility rates. For example, national lockdowns sharply reduced socialising. Young adults may have been particularly affected by this, with fewer opportunities to meet people and form romantic and sexual relationships. Meanwhile, increased uncertainties associated with the economic fallout of the pandemic might have deterred people from planning a baby.

We also put forward reasons why the pandemic may increase childbearing, including increased time spent together and a focus on home life among established couples. Furlough and working from home might have encouraged people in longer-term relationships to have children they may not otherwise have had, or that they might have had at a later time. Among parents already considering having another child at some point, births of subsequent children might have been brought forward.

Among younger adults, we found more reasons for a decline in childbearing than an increase, while among slightly older people we found more reasons to expect an increase.

The observed age-specific fertility trends are consistent with our predictions, though from this data we cannot know whether the reasons we proposed were exactly correct.

Looking back and looking forward

Historical evidence on fertility rates following the 2008 recession from other European countries suggests that it is younger people who are most likely to experience a decline in childbearing in response to shocks and crises.

Younger women have more opportunities to postpone their childbearing in response to uncertainties because they have more time to catch up on any births that had previously been put off.

Young people have been uniquely affected by the pandemic, being more likely to lose their jobs, or to change their living arrangements, often returning to their parents’ home. Among slightly older women, the pandemic could have increased fertility, for example, through more time spent with their partner, and changes in work-life balance due to COVID.

Read more:

Pandemic babies: how COVID-19 has affected child development

So what might the future hold in terms of fertility in the UK? Will the increasing birth rates among those in their 30s continue, with previously postponed births caught up at later ages? If this happens, we could see an increase in fertility rates.

Or is the pandemic bounce-back in childbearing a blip in an otherwise downward trend in fertility? Increased economic uncertainty, difficulties in securing stable, affordable housing, a greater awareness of environmental concerns and worries about global security are all likely to diminish certain people’s desires to have children.

Ultimately, it will be some years before we know whether the pandemic’s effects on childbearing are temporary or will be longer lasting.

![]()

Ann Berrington receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/S009477/1). This article is based on findings from the Understanding Recent Fertility Trends Project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The authors would like to acknowledge the rest of the project team — Sarah Christison, Bernice Kuang and Hill Kulu — who also contributed to this article.

Joanne Ellison receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/S009477/1)