Varlamova Lydmila/Shutterstock

From CSI to Law and Order, Line of Duty and Midsomer Murders, there is huge public fascination with crime and the criminal justice system. Especially when things come to a climactic ending and jurors decide on a defendent’s fate. But how much do jurors get it wrong? Will the jury convict an innocent person, or might they free a guilty person?

Ultimately, who committed the crime is often not easy to know, and jurors have to subjectively evaluate the evidence. But finding out what goes on inside the jury room and the biases that might influence jurors themselves is of huge interest and importance.

As psychologists, we can delve into jury decision making, as it requires several different areas of psychological research (cognitive psychology, social psychology, and individual differences) to unlock the processes behind the decisions jurors reach. The aim of our recent review was to bring together different areas of psychology to identify potential sources of bias that may influence how jurors make decisions.

The big three biases

We identified three main sources of bias: pre-trial bias; cognitive bias and bias originating from expert witnesses.

A significant part of the research literature has highlighted that pre-trial biases can influence the judgments of jurors. In 2008 researchers developed the pre-trial juror attitude questionnaire (PJAQ).

The scale measures biases that might influence juror decision making. For example, it measures biases such as racial biases and system confidence – how much faith (or not) the juror has in the criminal justice system. Through measuring these biases, we can get an indication into how strong a bias a person may have towards either the prosecution or defence. Interestingly, the PJAQ has often been shown to predict the verdict reached by jurors, with those who have a pro-prosecution bias reaching more guilty verdicts.

Due to pre-trial bias, some jurors are unable to take part in a criminal trial with an “innocent until proven guilty” mindset, even if they try. Jurors, like most humans, are not always rational, and may struggle to process and utilise all the available information in a reasoned manner.

This tendency often leads to biased decision making that can lead to errors. For example, research from 2001 found that jurors may favour particular verdicts as a trial progresses, despite being warned against doing this by a judge.

These preferences can lead to those jurors distorting the evidence against their preferred verdict or giving more weight to the evidence that favours their preference, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias.

Jurors who enter the courtroom with a bias towards the prosecution are more likely to see the evidence from the prosecution’s perspective, and dismiss the evidence presented from the defence (and vice versa when jurors have a defence bias). So initial pre-trial biases interact with cognitive mechanisms (for example, thinking, perception, memory) to cause the effects of bias to snowball.

Another origin of bias in jurors may come from “objective” and scientific expert witnesses. Researchers such as co-author Itiel Dror have shown that expert witnesses are far from objective decision makers and that irrelevant contextual information (provided, potentially, through the police) can bias their judgments and cause errors.

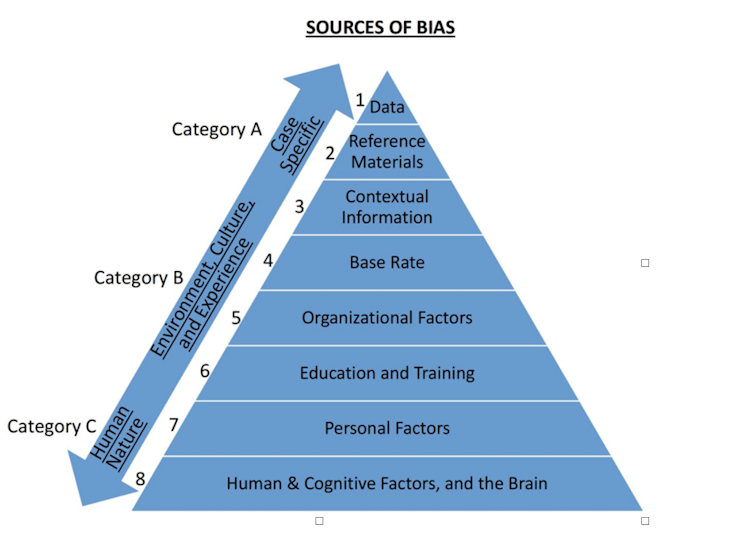

The diagram below shows the factors that might influence a forensic expert’s analysis. Through presenting expert testimony, biased conclusions could end up influencing the jury.

Itiel Dror, Author provided

Balancing the bias

We have made several recommendations in our review. First, we suggest a jury selection procedure, using measures like the PJAQ, where jurors with prejudicial biases are weeded out from the jury pool.

Second, such procedures could also be used to create a jury with a representative pool of biases. As fallible beings, humans are likely to always have some form of bias. If the most negative of biases, such as racial biases, are removed from the jury pool, other biases could be counteracted through a mix of jurors with different beliefs and biases – for example people with confidence in the criminal justice system vs. people with little faith in the system deliberating with one another – deliberating with one another. More research is needed though, as very little has been conducted on jury deliberations.

A third suggestion is for the criminal justice system to tackle bias by protecting forensic experts from undue influences, so that powerful but biased expert evidence does not influence the jury. For example, an expert’s testimony may be biased if they knew about another piece of unrelated evidence, such as a confession, during analysis.

Methods of counteracting bias in forensic examiners include using expert witnesses not associated with either side of the adversarial system, and for labs to use techniques such as Linear Sequential Unmasking (LSU).

LSU is a technique where forensic experts analyse the information in a specific sequence in isolation from any other reference material. So, for example, first they would analyse the evidence at the crime scene such as fingerprints. But they would not have access at this point to any material pertaining to the “target” suspect, such as their fingerprints. The reference material would then be analysed and later compared to the evidence gathered. LSU ensures sequencing of the relevant contextual information so that the more objective and less biasing information is prioritised.

Bias is a significant issue in the criminal justice system and can lead to miscarriages of justice. Through researching the sources and effects, psychologists can aid the criminal justice system by helping those involved establish procedures that avoid the potential for bias to influence the process.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.