Nobody is more excited for the release of a census than a genealogist. I have been researching family trees for 20 years and I have seen the release of key documents, including the 1911 census and the 1939 register, which the government used to issue ration books, among other wartime initiatives.

But no documents have received the same hype as the 1921 census of England and Wales, which is now accessible online (for a fee). Alternatively, if you visit the National Archives in London, the Manchester Central Library on St Peter’s Square in Manchester or the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, you can access it for free.

It contains information on more than 38 million people from more than 8.5 million households. And it is particularly significant because, as historian David Olusoga highlights, it is the last many of us will be able to peruse.

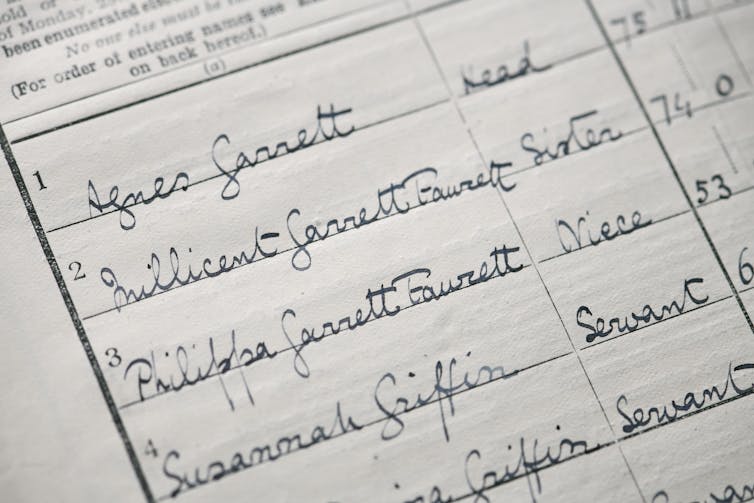

BUCK Find My Past Census, Author provided

Census data is only made public after 100 years. The 1931 census was destroyed in a fire in 1942 at a store in Middlesex. And obviously, no count was undertaken in 1941 due to the second world war. So the next will be that of 1951, to be released in 2052.

New questions

The modern census has been taken every ten years since 1801, the only exception being in 1941. Between 1801-1840, it was little more than a headcount, taken on a specific night, so that nobody could be counted twice.

The first detailed census that named individuals was released in 1841. People were asked to specify their name, address, sex, occupation and birth. For those over 15 years, their age was rounded to the nearest five years; children’s ages were recorded correctly.

The 1911 census asks how many years a couple have been married, how many children were born alive and how many children have died, and it also asks how many rooms were in the house. This data is really helpful for family historians because it assists in finding birth, marriage and death records and can shed new light on family mortality. Knowing the size of a house is also useful because it can give an indication of the financial position of the head of the household. It also helps to identify the type of house it is.

This data no longer features here. Although there is no official explanation, the questions any census contains tend to align with broader social issues.

In 1911, there was concern in government about declining birth rates, at a time when Britain needed a strong workforce to maintain its position within Europe. In 1921, meanwhile, the focus was on the impact the first world war had had on children. The census asks for the living status of parents, to see how many children were orphaned.

Societal changes

The broader impact of the conflict is clear, with 1.7 million more women registered than men and more than 730,000 fatherless children. And the post-war recession is made visible too, in many families’ records, including my own.

The census reveals that three of my great grandfathers, who were the head of their households (that is, the person filling out the census entry) were out of work. One of my great grandfathers, who the 1911 census had shown to be employed as a labourer, couldn’t physically work because of injuries he had sustained during the 1914-1918 war. Unemployment rose to an average of 11.5% between 1921-22, affecting many working-class families.

Compared to previous censuses, the 1921 data shows more children in education. This is because the school-leaving age was increased to 14 years old in 1918. One child featured was the Academy Award-winning actor Laurence Olivier. In 1921, aged 14 years and one month, Olivier could legally leave school. The census however registers him as a pupil at All Saints Choir School in London. It also shows that his mother, Agnes Crookenden, had died.

Divorce is recognised here for the first time, with more than 15,000 people classing themselves as “divorced”. Though still relatively difficult to obtain at this time, especially if you were a woman and were not wealthy, national divorce rates increased sixfold after the first world war, peaking in 1921. Whereas men could divorce on the grounds of adultery alone, women had to prove adultery and one other matrimonial offence.

One divorcee listed on the census is Annie Julia Havelock (1872-1953), daughter of the wealthy Sir William Chaytor (1837-1896), former inspector of factories. Havelock divorced her husband Allan Havelock Allen in 1913 on the grounds of adultery, cruelty and desertion. Her census entry shows that she is living with her daughter and a servant. Under the condition of marriage, she has written a rather large “D” for divorced.

In terms of employment, the 1921 census includes details of employers for the first time. We see a wider variety of occupations for women, partly because this comes after the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act 1919, which allowed women access to professions in law and the civil service.

Helena Normanton, who was called to the bar alongside eight other women in 1922 and became the female barrister to be briefed in the High Court, was one of the first women to study law, as a consequence of that act. The 38-year-old can be found on the census living independently at 22 Mecklenburgh Street in St Pancras, London. Under “occupation”, she lists law student, lecturer, home duties and writer.

Because of the questions it no longer features, the 1921 census is less exciting compared with that of 1911, especially for family historians. But what is special about it is not the new questions it asks, but the period it paints. This census, as cultural historian Professor Matt Houlbrook tells me, “effectively freezes a society that is in motion. It is poised right between the upheaval of the Great War, desperate efforts at post-war reconstruction, and the transformative social, cultural, economic and political changes of the 1920s.”

Michala Hulme has given talks on genealogy for Find my Past and is the co-host of Ancestry’s Behind the Headlines of History podcast.