Sometimes the most powerful tool in research is people spending a few minutes to record their observations while going about their daily lives. An early example of this sort of “citizen science” is the annual garden bird watch in the UK, which has been running since 1978 and is organised by the nature conservation charity, RSBP. All you need do to take part is spending an hour watching the wildlife in you garden or local park.

Today, citizen science projects are increasingly popular, with people surveying and monitoring everything from weather events, invasive plant species and ladybirds to planets orbiting stars other than our Sun.

As the citizen science field has developed, boundaries have blurred and scientists have begun involving citizens as more active researchers – carrying out important experiments, collecting environmental measurements and generating data.

Here are five just such projects with a distinctly chemical theme.

RiverDip

Our new paper, published in PLOS One, presents the results of such a project, RiverDip, which enables and encourages citizens to monitor the chemical health of their local waterways.

This involves monitoring phosphates and nitrates – essential nutrients, making up the basis of agricultural fertilisers. But if they run off fields and into waterways they cause significant problems.

The fertilisers encourage rapid growth of algae and weeds, which form dense green mats on the surface of waterways. These block out the light to other plants. What’s more, later, when they rot they use up some of the dissolved oxygen in the water, resulting in deoxygenation that harms other aquatic plants and animals.

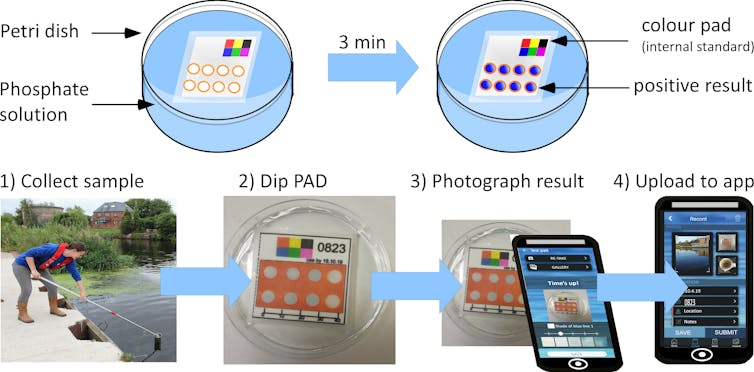

RiverDip was developed as part of the EU-funded Sullied Sediments project as a means to allow citizens to monitor the phosphate levels in waterways. We provided interested folk with paper-based sensors that change colour in the presence of phosphates. The measurement takes just three minutes. After it’s done, volunteers upload their results via a bespoke mobile app.

Together we have collected hundreds of measurements and begun to map phosphate levels across the Europe’s North Sea Region, consisting of countries including the Scandinavian nations, England, the Netherlands and Germany. Having lots of measurements from different seasons will help us to understand how nutrient levels change over time, and we are currently looking for interested volunteer groups to continue this project.

The Big Compost experiment

If you like rummaging in the garden, this one is for you. Lots of packaging is now labelled as biodegradable or compostable, but what does this really mean and do these products really break down in a domestic compost bin? The Big Compost experiment investigates new ways of reducing plastic waste, asking participants to check how well biodegradable and compostable packaging breaks down.

You can help answer these questions by simply bagging up materials that claim to be compostable (such as some tea bags, carrier bags and disposable cups), placing them in your compost heap and then observing what happens. You can record your results via the experiment’s home page.

Fold-at-home

If you fancy something easier and less messy, there are some great projects which you can contribute to from the comfort of your sofa.

Proteins are the molecular machines that govern all the chemical processes and interactions that make up a living organism. And like any machine (be it a proteins or a motor car), they help to understand how all the parts fit together when designing modifications and upgrades. So understanding proteins’ incredibly complex structures, how they interact with each other and potential drugs provides pharmaceutical developers with critical information that allows them to design more effective therapeutics. But modelling this requires vast amounts of computing power. One approach would therefore be to use vast amounts of money to build a computer dedicated to solving this problem.

But scientists have realised that, alternatively, you could ask people to contribute spare computing power of their home PCs to form a giant global supercomputer. All you need do is install the Fold-at-home software on your computer and when you nip off to make a cup of tea or plug into the television, your computer gets to work on folding proteins, which could lead to the development of COVID drugs or cancer therapies.

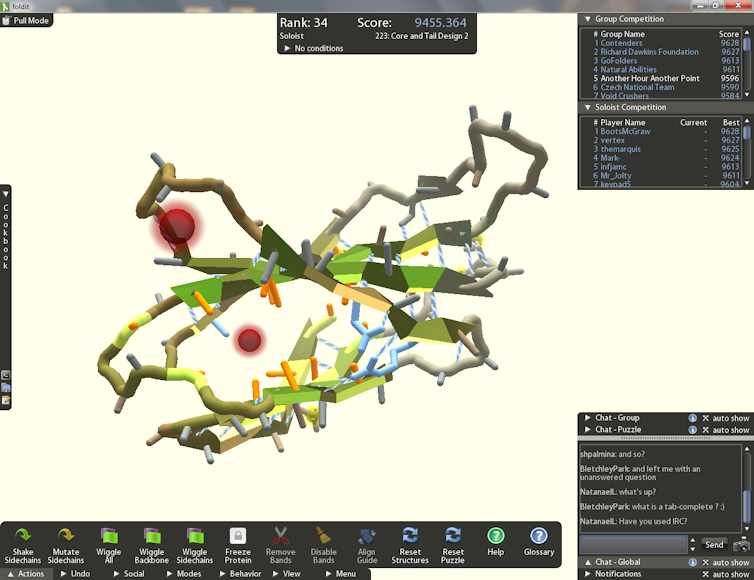

Fold-It

If puzzles and computer games are more your cup of tea, you may enjoy Fold-it. This project attempts to predict the structure of a protein, but this time it needs a bit more human input. It takes advantage of people’s puzzle-solving intuitions when playing games competitively and challenges them to fold the best proteins.

Animation Research Labs, University of Washington

This information helps researchers understand if human pattern recognition and puzzle solving abilities are better than current computer programs. Such information could be used to develop new computer strategies to predict protein structures even faster. This is really helpful as understanding how proteins fold and interact enables scientists to develop new proteins to help combat diseases such as Alzheimer’s and HIV/AIDS.

Sensor community

The sensor community project aims to build a network of small sensors to collect and openly share environmental data such as the nitrogen dioxide air pollution generated by internal combustion engines and burning of fossil fuels.

Currently, the community has constructed and deployed nearly 14,000 active sensors in 69 countries, all of which are returning data in real time. To take part in this project, you build sensors using kits developed by the researchers and place them somewhere. The project has different communities that focus on different aspects of environmental pollution (including noise).

Getting involved in these kind of citizen sciences projects can be a great way to have a positive impact on the world, collecting large volumes of data that enable us to understand our impact on the planet.

![]()

Mark Lorch receives funding from European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg VB North Sea Region Programme

[email protected] receives funding from European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg VB North Sea Region Programme.