READER QUESTION: My understanding is that nothing comes from nothing. For something to exist, there must be material or a component available, and for them to be available, there must be something else available. Now my question: Where did the material come from that created the Big Bang, and what happened in the first instance to create that material? Peter, 80, Australia.

“The last star will slowly cool and fade away. With its passing, the universe will become once more a void, without light or life or meaning.” So warned the physicist Brian Cox in the recent BBC series Universe. The fading of that last star will only be the beginning of an infinitely long, dark epoch. All matter will eventually be consumed by monstrous black holes, which in their turn will evaporate away into the dimmest glimmers of light. Space will expand ever outwards until even that dim light becomes too spread out to interact. Activity will cease.

Or will it? Strangely enough, some cosmologists believe a previous, cold dark empty universe like the one which lies in our far future could have been the source of our very own Big Bang.

This article is part of Life’s Big Questions

The Conversation’s new series, co-published with BBC Future, seeks to answer our readers’ nagging questions about life, love, death and the universe. We work with professional researchers who have dedicated their lives to uncovering new perspectives on the questions that shape our lives.

The first matter

But before we get to that, let’s take a look at how “material” – physical matter – first came about. If we are aiming to explain the origins of stable matter made of atoms or molecules, there was certainly none of that around at the Big Bang – nor for hundreds of thousands of years afterwards. We do in fact have a pretty detailed understanding of how the first atoms formed out of simpler particles once conditions cooled down enough for complex matter to be stable, and how these atoms were later fused into heavier elements inside stars. But that understanding doesn’t address the question of whether something came from nothing.

So let’s think further back. The first long-lived matter particles of any kind were protons and neutrons, which together make up the atomic nucleus. These came into existence around one ten-thousandth of a second after the Big Bang. Before that point, there was really no material in any familiar sense of the word. But physics lets us keep on tracing the timeline backwards – to physical processes which predate any stable matter.

This takes us to the so-called “grand unified epoch”. By now, we are well into the realm of speculative physics, as we can’t produce enough energy in our experiments to probe the sort of processes that were going on at the time. But a plausible hypothesis is that the physical world was made up of a soup of short-lived elementary particles – including quarks, the building blocks of protons and neutrons. There was both matter and “antimatter” in roughly equal quantities: each type of matter particle, such as the quark, has an antimatter “mirror image” companion, which is near identical to itself, differing only in one aspect. However, matter and antimatter annihilate in a flash of energy when they meet, meaning these particles were constantly created and destroyed.

But how did these particles come to exist in the first place? Quantum field theory tells us that even a vacuum, supposedly corresponding to empty spacetime, is full of physical activity in the form of energy fluctuations. These fluctuations can give rise to particles popping out, only to be disappear shortly after. This may sound like a mathematical quirk rather than real physics, but such particles have been spotted in countless experiments.

The spacetime vacuum state is seething with particles constantly being created and destroyed, apparently “out of nothing”. But perhaps all this really tells us is that the quantum vacuum is (despite its name) a something rather than a nothing. The philosopher David Albert has memorably criticised accounts of the Big Bang which promise to get something from nothing in this way.

Wikimedia/Ahmed Neutron

Suppose we ask: where did spacetime itself arise from? Then we can go on turning the clock yet further back, into the truly ancient “Planck epoch” – a period so early in the universe’s history that our best theories of physics break down. This era occurred only one ten-millionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang. At this point, space and time themselves became subject to quantum fluctuations. Physicists ordinarily work separately with quantum mechanics, which rules the microworld of particles, and with general relativity, which applies on large, cosmic scales. But to truly understand the Planck epoch, we need a complete theory of quantum gravity, merging the two.

We still don’t have a perfect theory of quantum gravity, but there are attempts – like string theory and loop quantum gravity. In these attempts, ordinary space and time are typically seen as emergent, like the waves on the surface of a deep ocean. What we experience as space and time are the product of quantum processes operating at a deeper, microscopic level – processes that don’t make much sense to us as creatures rooted in the macroscopic world.

In the Planck epoch, our ordinary understanding of space and time breaks down, so we can’t any longer rely on our ordinary understanding of cause and effect either. Despite this, all candidate theories of quantum gravity describe something physical that was going on in the Planck epoch – some quantum precursor of ordinary space and time. But where did that come from?

Even if causality no longer applies in any ordinary fashion, it might still be possible to explain one component of the Planck-epoch universe in terms of another. Unfortunately, by now even our best physics fails completely to provide answers. Until we make further progress towards a “theory of everything”, we won’t be able to give any definitive answer. The most we can say with confidence at this stage is that physics has so far found no confirmed instances of something arising from nothing.

Cycles from almost nothing

To truly answer the question of how something could arise from nothing, we would need to explain the quantum state of the entire universe at the beginning of the Planck epoch. All attempts to do this remain highly speculative. Some of them appeal to supernatural forces like a designer. But other candidate explanations remain within the realm of physics – such as a multiverse, which contains an infinite number of parallel universes, or cyclical models of the universe, being born and reborn again.

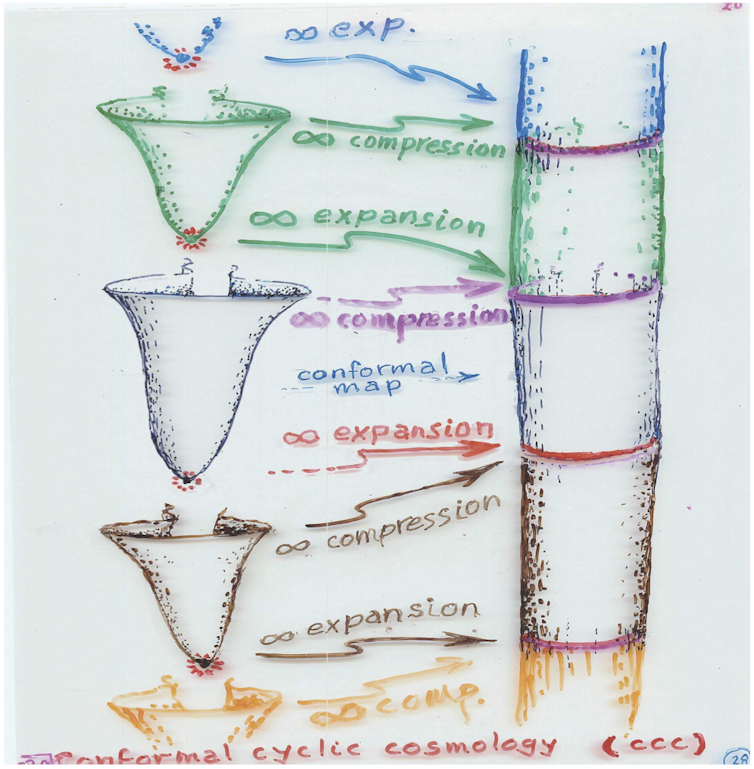

The 2020 Nobel Prize-winning physicist Roger Penrose has proposed one intriguing but controversial model for a cyclical universe dubbed “conformal cyclic cosmology”. Penrose was inspired by an interesting mathematical connection between a very hot, dense, small state of the universe – as it was at the Big Bang – and an extremely cold, empty, expanded state of the universe – as it will be in the far future. His radical theory to explain this correspondence is that those states become mathematically identical when taken to their limits. Paradoxical though it might seem, a total absence of matter might have managed to give rise to all the matter we see around us in our universe.

In this view, the Big Bang arises from an almost nothing. That’s what’s left over when all the matter in a universe has been consumed into black holes, which have in turn boiled away into photons – lost in a void. The whole universe thus arises from something that – viewed from another physical perspective – is as close as one can get to nothing at all. But that nothing is still a kind of something. It is still a physical universe, however empty.

How can the very same state be a cold, empty universe from one perspective and a hot dense universe from another? The answer lies in a complex mathematical procedure called “conformal rescaling”, a geometrical transformation which in effect alters the size of an object but leaves its shape unchanged.

Penrose showed how the cold dense state and the hot dense state could be related by such rescaling so that they match with respect to the shapes of their spacetimes – although not to their sizes. It is, admittedly, difficult to grasp how two objects can be identical in this way when they have different sizes – but Penrose argues size as a concept ceases to make sense in such extreme physical environments.

In conformal cyclic cosmology, the direction of explanation goes from old and cold to young and hot: the hot dense state exists because of the cold empty state. But this “because” is not the familiar one – of a cause followed in time by its effect. It is not only size that ceases to be relevant in these extreme states: time does too. The cold dense state and the hot dense state are in effect located on different timelines. The cold empty state would continue on forever from the perspective of an observer in its own temporal geometry, but the hot dense state it gives rise to effectively inhabits a new timeline all its own.

It may help to understand the hot dense state as produced from the cold empty state in some non-causal way. Perhaps we should say that the hot dense state emerges from, or is grounded in, or realised by the cold, empty state. These are distinctively metaphysical ideas which have been explored by philosophers of science extensively, especially in the context of quantum gravity where ordinary cause and effect seem to break down. At the limits of our knowledge, physics and philosophy become hard to disentangle.

Experimental evidence?

Conformal cyclic cosmology offers some detailed, albeit speculative, answers to the question of where our Big Bang came from. But even if Penrose’s vision is vindicated by the future progress of cosmology, we might think that we still wouldn’t have answered a deeper philosophical question – a question about where physical reality itself came from. How did the whole system of cycles come about?

Then we finally end up with the pure question of why there is something rather than nothing – one of the biggest questions of metaphysics.

But our focus here is on explanations which remain within the realm of physics. There are three broad options to the deeper question of how the cycles began. It could have no physical explanation at all. Or there could be endlessly repeating cycles, each a universe in its own right, with the initial quantum state of each universe explained by some feature of the universe before. Or there could be one single cycle, and one single repeating universe, with the beginning of that cycle explained by some feature of its own end. The latter two approaches avoid the need for any uncaused events – and this gives them a distinctive appeal. Nothing would be left unexplained by physics.

Roger Penrose

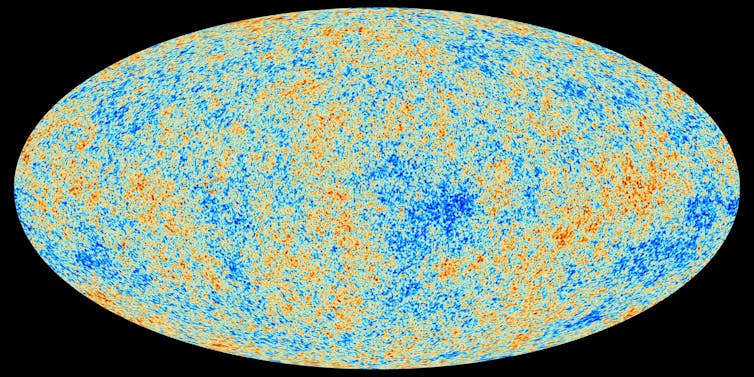

Penrose envisages a sequence of endless new cycles for reasons partly linked to his own preferred interpretation of quantum theory. In quantum mechanics, a physical system exists in a superposition of many different states at the same time, and only “picks one” randomly, when we measure it. For Penrose, each cycle involves random quantum events turning out a different way – meaning each cycle will differ from those before and after it. This is actually good news for experimental physicists, because it might allow us to glimpse the old universe that gave rise to ours through faint traces, or anomalies, in the leftover radiation from the Big Bang seen by the Planck satellite.

Penrose and his collaborators believe they may have spotted these traces already, attributing patterns in the Planck data to radiation from supermassive black holes in the previous universe. However, their claimed observations have been challenged by other physicists and the jury remains out.

ESA and the Planck Collaboration

Endless new cycles are key to Penrose’s own vision. But there is a natural way to convert conformal cyclic cosmology from a multi-cycle to a one-cycle form. Then physical reality consists in a single cycling around through the Big Bang to a maximally empty state in the far future – and then around again to the very same Big Bang, giving rise to the very same universe all over again.

This latter possibility is consistent with another interpretation of quantum mechanics, dubbed the many-worlds interpretation. The many-worlds interpretation tells us that each time we measure a system that is in superposition, this measurement doesn’t randomly select a state. Instead, the measurement result we see is just one possibility – the one that plays out in our own universe. The other measurement results all play out in other universes in a multiverse, effectively cut off from our own. So no matter how small the chance of something occurring, if it has a non-zero chance then it occurs in some quantum parallel world. There are people just like you out there in other worlds who have won the lottery, or have been swept up into the clouds by a freak typhoon, or have spontaneously ignited, or have done all three simultaneously.

Some people believe such parallel universes may also be observable in cosmological data, as imprints caused by another universe colliding with ours.

Many-worlds quantum theory gives a new twist on conformal cyclic cosmology, though not one that Penrose agrees with. Our Big Bang might be the rebirth of one single quantum multiverse, containing infinitely many different universes all occurring together. Everything possible happens – then it happens again and again and again.

An ancient myth

For a philosopher of science, Penrose’s vision is fascinating. It opens up new possibilities for explaining the Big Bang, taking our explanations beyond ordinary cause and effect. It is therefore a great test case for exploring the different ways physics can explain our world. It deserves more attention from philosophers.

For a lover of myth, Penrose’s vision is beautiful. In Penrose’s preferred multi-cycle form, it promises endless new worlds born from the ashes of their ancestors. In its one-cycle form, it is a striking modern re-invocation of the ancient idea of the ouroboros, or world-serpent. In Norse mythology, the serpent Jörmungandr is a child of Loki, a clever trickster, and the giant Angrboda. Jörmungandr consumes its own tail, and the circle created sustains the balance of the world. But the ouroboros myth has been documented all over the world – including as far back as ancient Egypt.

Djehouty/Wikimedia

The ouroboros of the one cyclic universe is majestic indeed. It contains within its belly our own universe, as well as every one of the weird and wonderful alternative possible universes allowed by quantum physics – and at the point where its head meets its tail, it is completely empty yet also coursing with energy at temperatures of a hundred thousand million billion trillion degrees Celsius. Even Loki, the shapeshifter, would be impressed.

To get all of life’s big answers, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value evidence-based news by subscribing to our newsletter. You can send us your big questions by email at [email protected] and we’ll try to get a researcher or expert on the case.

More Life’s Big Questions:

-

Happiness: is contentment more important than purpose and goals?

-

Could we live in a world without rules?

-

Death: can our final moment be euphoric?

-

Nature: have humans now evolved beyond the natural world, and do we still need it?

-

Love: is it just a fleeting high fuelled by brain chemicals?

![]()

Alastair Wilson receives funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 757295), and from the Australian Research Council (grant agreement no. DP180100105).