The Black Lives Matter movement and the harrowing events that gave rise to it have ensured that global attention remains focused on the enduring legacy of African American slavery. There are numerous ways its continued relevance persists in the public eye, from debates over reparations for Black people in the US and how slavery’s history is taught in schools, to a number of recent big Hollywood films and popular TV shows.

The legacy of racism and violence that originated in slavery, and which continued throughout the Jim Crow period of segregation, also survives in many forms today, from persistent inequality to police brutality and the denial of Black people’s democratic rights.

What often gets lost in the discussion of slavery are the experiences of free Black people who co-existed throughout the entire period of enslavement. Of the 20 Africans first traded to British settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, some served out their indentures and became free.

A parallel experience

Granted, the numbers of free Black people were always significantly smaller than those who were enslaved, but there were communities all over what would become the United States. On the eve of the American Civil War in 1860 – a conflict fought over slavery – free Black people numbered 488,000 in the US compared to 4 million enslaved – not an insignificant number.

A parallel and often intertwined experience, freedom and was not always a permanent condition, but one marked with permeable boundaries between enslavement and liberty. As well-known figures like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth – both escaped slaves who became abolitionists and reformers – demonstrated, one could be born into slavery and eventually gain one’s freedom.

In my book Generations of Freedom: Gender, Movement, and Violence in Natchez 1779-1865, I distinguish between those who were born into the system of slavery and later freed – the foundational generation – and those who were born free, known as the conditional generations.

Regardless of which generation they belonged to, a free Black person’s ability to exist within this ambiguous state of liberty was not guaranteed. Although they were technically free – not legally owned – there were limitations on their freedom.

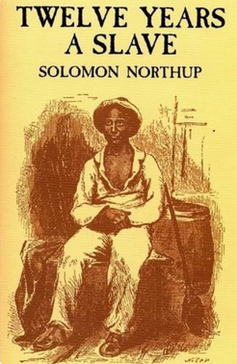

Just like Solomon Northup, whose experiences are related in his autobiography Twelve Years a Slave, some people in Natchez, Mississippi, had been born into freedom only to be kidnapped and illegally enslaved. Others lost their freedom for being prosecuted for crimes like living without a proper licence as a free person of colour or incurring jail costs for being held as a runaway.

Becoming – and staying – free

Free Black people lived complicated lives and had to work to ensure their survival in Natchez on the Mississippi River, one of the wealthiest cotton-growing areas in the South. In 1860, Mississippi had one of the largest enslaved populations (436,631), but a relatively tiny number of free Black people (775). Natchez contained the biggest free Black community in the state with 225, dwarfed by the 14,292 who were enslaved.

People became free in a variety of ways. Some families’ origins derived from enslaved women who were in sexual relationships with white men. A number of these women gave birth to children in slavery and then worked for the liberty of themselves and their families.

In some cases they inherited property in addition to their freedom or worked to save money to purchase themselves out of slavery. Others were promised their future freedom and entered into contracts to work for a number of years before they were freed, all of which different paths to independence.

But however freedom was acquired, it was often limited and contested. Free Black people lived under a different justice system with a higher level of scrutiny by the local police board and state. They had to prove themselves of “good character”, “industrious” and “lawful” or they could be imprisoned or ordered to leave the state.

World of Books

Legislation was passed to prevent free Black people from voting, from serving on juries and on commissions, and engaging in certain occupations such as selling alcohol, operating houses of entertainment or printing establishments – even though they were taxpayers. Their movements were monitored, and suspicion inevitably fell upon them for crimes or during times of slave insurrection.

Despite these challenges, free Black people managed to create community through friendships and kin networks, buy property, build businesses, educate their children and use the court systems to protect their freedoms – in short, to survive and thrive.

Along with the enslaved, their experiences laid the foundation for the development of the uneven colour-conscious system of democracy and criminal justice in the US. The end of slavery did not result in unconditional freedom in 1865. Ever since, people of African descent have had to contend with severe disparities in employment, health, education, voting rights, wealth and countless other factors persisting to this day.

Black people live under a dual criminal justice system that subjects them to heavier policing, racially biased stops, searches and seizures, imprisonment, violence, and even death at the hands of the state. In so many ways, the experiences of free Black people during the era of slavery provided a blueprint for the way future generations would have to negotiate the world.

![]()

Nik Ribianszky is affiliated with the Enslaved: People of the Historical Slave Trade project.