When we talk about how well or badly a government is doing, we often base that discussion around polling that shows how people say they are going to vote in the next election.

Recent polling, for example, puts the Conservatives comfortably ahead of Labour in voting intentions – although the gap has narrowed since the start of the year.

This is perhaps surprising. The expectation might be that Labour should be well ahead given that recent weeks have been characterised by empty supermarket shelves, drivers being unable to get petrol and millions of universal credit recipients receiving a large cut to their benefits. Meanwhile, the costs of both heating and eating are rapidly increasing.

It may be, however, that we are looking in the wrong place when judging the public’s reaction to the government. The voting intention question is hypothetical when the general election is years into the future. It is more sensible to ask a question about how the government is currently performing, rather than about voting intentions. Another question regularly asked by pollsters may be more indicative of what is happening to public attitudes.

That question is: “Do you approve or disapprove of the government’s record to date?” In other words, it asks about the government’s performance rather than about its promises and rhetoric. An equivalent question in the US about the president’s performance is followed closely by political pundits, but the responses to the question in the UK are largely ignored.

Government approval/disapproval December 2019 to September 2021

YouGov, Author provided

Looking at how people answered this question in successive YouGov surveys conducted since the December 2019 general election gives a rather different picture to voting intention.

The public’s response to the initial shock of the pandemic in early 2020 was very positive for the government. It was what US pollsters call a “rally round the flag” response, with large numbers backing the government in its plans to deal with COVID.

However, by the summer of 2020, many voters had become disillusioned with the actual performance of the government’s handling of the pandemic, and disapproval ratings soared. But the arrival of the successful vaccination programme then gave a significant boost to the approval ratings as the rollout accelerated in the early part of 2021. This trend peaked in May and since then approval has fallen dramatically. It is likely that this decline will continue up to Christmas if shortages in the shops aren’t resolved and the cost of living continues to rise.

A lesson from history

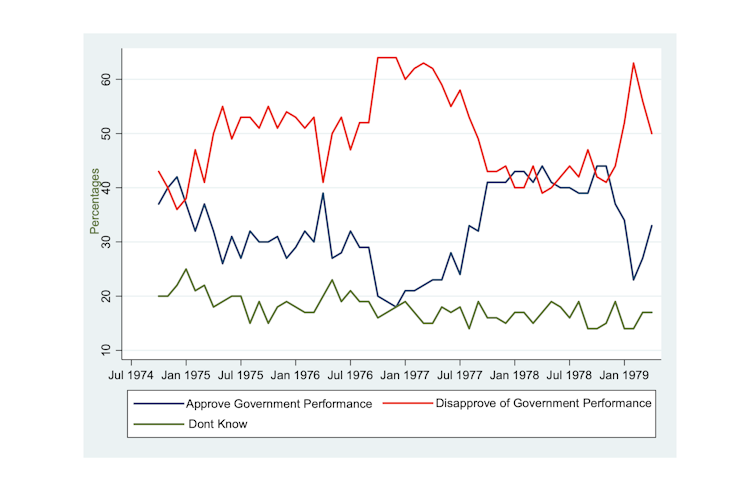

This picture is uncannily similar to the experience of the Labour government elected with a small majority in October 1974. Figure 2 below shows approval ratings for this government up to the general election of 1979.

At that time, Prime Minister James Callaghan was grappling with the fallout from the quadrupling of oil prices by the Opec oil cartel following the Arab-Israeli war of 1973. Inflation was rampant and his solution was to impose wage restraint. That triggered more than 2,000 strikes across the country in what is now referred to as the “winter of discontent”.

Government approval/disapproval, October 1974 to April 1979

Paul Whiteley and Harold Clarke, Author provided

A look at the polling carried out in the run-up to the 1979 election show the Labour government rapidly became unpopular as inflation took off from 1974, but approval ratings recovered by the start of 1978 as it abated. By the summer of 1978, the prime minister was considering an autumn election, but Labour’s lead in the polls was very narrow, so he waited until the spring of 1979, hoping that things would improve. However, during that winter, the government’s approval ratings crashed as a result of the mounting industrial unrest, and Margaret Thatcher won the general election in May 1979.

Labour’s problem at that time was a familiar one to all incumbent governments – a failure to manage the economy properly as far as the voters were concerned. This carries the implication that the success of current prime minister Boris Johnson in the next election will depend on the extent to which the economy recovers after the double whammy of Brexit and the pandemic.

At the moment, the economy is bouncing back and unemployment has been falling, but the most recent report from the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee flags slower growth and rising inflation next year, making a rapid economic recovery doubtful.

Research by IMF economists has concluded that recovery from major shocks such as wars, pandemics and serious economic recessions is slow and sometimes does not happen at all. Their analysis used data from 190 countries over a period of 40 years to examine this issue and concluded that: “the magnitude of persistent output losses ranges from around 4% to 16% for various shocks”.

If this happens, Johnson will seek re-election in a very bleak economic environment, stretching his ability to cheerlead recovery and to “level-up” Britain in practice as opposed to in rhetoric.

![]()

Paul Whiteley receives funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

Harold D Clarke does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.