In September 1941 the British press enthralled its readers with a story of naval heroism that the public, battered by German bombing and strict rationing, was crying out for: a tale of survival against the odds.

My research involves looking at how the British media covered the second world war. When I came across this story, I was struck by the way in which the navy kept the it quiet for nearly two years.

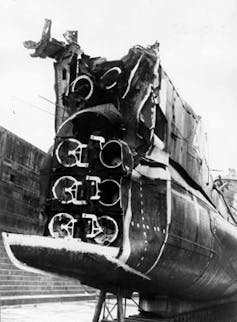

On September 15 1941, the Daily Mail reported that in December 1939, the Royal Navy submarine HMS Triumph had been sailing on the surface in the Skagerrak Strait between Denmark and Germany when it hit a mine. The newspaper account described how the deadly device split the air with a colossal explosion that “temporarily blinded the men on the bridge”. Its rival paper, the Daily Mirror, explained that the mine had blow off an 18-foot-long section of Triumph’s bows and opened “a 12-foot split in her hull amidships”.

Triumph was in German-patrolled waters and so badly damaged that she could not dive. She was leaking copiously, and her pumps were working flat out. Undaunted, the Triumph’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander John Wentworth McCoy, brought her slowly home to the Firth of Forth in Scotland. The 300-mile journey was made at speeds as low as 2.5 knots, exposing Triumph to German bombing. As she approached the Scottish coast, a Dornier bomber found her and prepared to attack. Before it could deliver a fatal blow, British fighters drove it off.

Triumph staggered back to port with nothing but a crumpled bulkhead between her crew and death. The Daily Mirror noted that a damaged torpedo in her shattered bow had been armed throughout the voyage and might have exploded. Triumph’s steering gear, it noted, “seemed held together by a miracle”. The Daily Telegraph reflected that “only good material and excellent workmanship” had prevented her “literally falling to pieces”.

In the gloom of the phoney war of 1940, workers at the Vickers yard in Barrow-in-Furness – where Triumph had been launched in 1938 – might have been proud to read that. But they could not – nor could anyone else. Triumph hit the mine on Boxing Day 1939, but not a word was published about her voyage or the bravery of her crew until 21 months later. It was a stark example of the power that the various armed services ministries had to silence the press.

Senior Service

Although Britain’s wartime governments recognised that statutory press censorship was incompatible with the democratic values Britain fought to defend, the ministries responsible for the Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force exercised rigid control over access to information about Britain’s armed forces. If they did not want to release it, they did not do so. The navy, fiercely proud of its status as the “Senior Service”, was notoriously conservative.

In his 1947 memoir, Blue Pencil Admiral, the wartime government’s chief press censor, Rear Admiral George Thompson, recalled that – long after the Army and the Royal Air Force learned to appreciate the value of publicity: “It was seldom that any naval news of real interest or importance was allowed to come out … until so long afterwards that all interest in the event had vanished.”

A proud submariner himself, Thompson cites the example of HMS Triumph as one that infuriated him. Thompson believed her voyage was a “magnificent story of the heroism and fortitude of the British sailor”. By delaying release of the details for so long, the Navy ensured that the voyage “lost its tense, human, immediate interest”. Thompson lamented that “it was a great story, and it was a pity that it could not have been released at the time”.

Imperial War Museums

He was right. It’s not clear from the public record what led to the news emerging, but Triumph’s story eventually appeared on the front page of the Daily Express on September 15 1941. Under the headline “Submarine lost 18 ft – Got Home”, Lord Beaverbrook’s market-leading paper described her “amazing exploit”. This was accompanied by a photograph of Triumph at her launch with the now-missing portion of the bow indicated by a wavy line. Other papers followed up the story, but none gave it such front-page treatment.

Chasing the story

If the navy’s approach to publicity was overly cautious, the Air Ministry was much more dynamic, allowing RAF press officers to mould stories of heroism during the Battle of Britain. Their promotion of heroes such as Douglas Bader, the amputee fighter ace won sympathetic, high-profile coverage in popular and elite newspapers.

Later they would promote Wing Commander Guy Gibson and his fellow Dambusters with equal enthusiasm. RAF press management helped to limit and delay criticism of the civilian casualties caused by area bombardment of German cities.

Among leading members of the wartime coalition, Winston Churchill and the home secretary, Labour’s Herbert Morrison, hated newspaper criticism and expended considerable energy to threaten editors who dared to challenge ministers in the interests of their readers.

The Daily Mirror, and its sister title the Sunday Pictorial, attracted particular venom. In 1940 Churchill described these mass circulation socialist tabloids as “vicious and malignant” and accused them of publishing “subversive articles”. Morrison urged MI5 to investigate these journalists with, as he described them, “diseased minds”.

But such political pressure should not distract our attention from the enormous power that the armed service ministries and the ministry of information possessed. By rationing access to information – and promoting only those stories they considered helpful – they achieved more than politicians threats would have done.

![]()

Tim Luckhurst has received research funding from News UK and Ireland Ltd. He is a fellow of the Royal Society for the Arts and a member of the Free Speech Union and the Society of Editors.